The love of a good mother: Ann MacDiarmid was mom to three Gold Medallists

By Jeannie Campbell

Supportive parents are a great asset for any young piper. They are there with encouragement and moral support; they provide transport to lessons or practices, buy instruments and equipment, and generally act as a backup team. You see the mothers at juvenile competitions, looking after the pipe case, fastening collars, straightening ties, holding the water bottle, locating a mislaid glengarry and being on hand with the sandwiches and drinks. Afterwards, she will probably be the one who is washing the shirt and socks, cleaning the muddy shoes, ironing the shirt, and polishing the trophies.

One mother who had more pipers to look after than most was Ann, wife of Malcolm (“Calum Piobair”) MacPherson. Not only was she the wife and mother of pipers, but she was mother to three Gold Medallists, a record which I think has only been equalled by Mrs. MacFadyen, mother of John, Iain and Duncan, and surpassed by no one.

We know that her name was Ann MacDiarmid; she was born in Kildalton, Islay, about 1837. Her parents were John MacDiarmid and Marion or Mary Keith. The records of her birth and her parent’s marriage cannot be found; neither can the family be located in the 1841 or 1851 census.

As related by her son Angus on a tape recording, family tradition has it that Malcolm accompanied Archie Munro on a visit to Angus MacKay in Islay, where he met and married Ann. This story is unlikely. Angus MacKay became piper to the Laird of Islay in 1835 but probably left in 1840 when he composed “Farewell to the Laird of Islay.” By May 1841, he was in Edinburgh where he married, and by the time of the Northern Meeting in October 1841, he was piper to Lord Ward, who had recently bought the Glengarry estate. He was still with Lord Ward in 1842; then, in April 1843, he became piper to Queen Victoria. Therefore, a meeting with Angus MacKay in Islay would have had to have taken place before 1840, when Malcolm would have been six years old and his wife-to-be even younger.

The story goes that he met his wife Ann McDiarmid at a tinker encampment. She had long red hair and was a lovely singer, and they fell in love and married the night they met; a tinker wedding and the only ceremony they had.

Another version of their meeting is more likely. The story goes that he met his wife Ann McDiarmid at a tinker encampment. She had long red hair and was a lovely singer, and they fell in love and married the night they met; a tinker wedding and the only ceremony they had.

At this time, Malcolm was living in Greenock. Their first child Mary was born and registered in Greenock in July 1856 but probably died young, as she does not appear again. Soon after her birth, in October 1856, Malcolm and Ann did have a proper legal wedding after banns according to the rites of the Church of Scotland by the minister of the Gaelic parish in Greenock. Malcolm, now aged 21, is described as a labourer. His father was Angus MacPherson, piper, and his deceased mother was Euphemia, maiden surname MacLeod. Malcolm was able to sign his name on his marriage certificate, but his wife was not. Ann was aged 19 and resident in Greenock. Her father, John MacDiarmid, was employed as a labourer and her mother was Marion, maiden surname Keith. According to Ann’s death certificate, her father was a fisherman, and her mother’s forename was Mary.

Malcolm’s mother had died before he was two, and Malcolm went to live with his maternal grandparents on the island of Raasay. His father, Angus, married again, but Malcolm was still with his grandparents in 1841. There were no others in the household apart from Malcolm MacLeod, aged 57; his wife Catherine, aged 50; and Malcolm Macpherson, aged seven. Malcolm’s stepmother died in 1847, and in 1849 his father married the third of his four wives. According to family tradition, Malcolm left home when he was very young because he did not get on with his stepmother. So Malcolm had never experienced a stable family life with a mother and siblings until his own marriage.

Ann and Malcolm’s second child Angus was born in Greenock in February 1858. Malcolm was still working as a labourer, according to the registration.

According to Malcolm’s son, Angus, his father saw an advertisement in a Greenock paper saying that the Captain of a boat wanted a piper, and Malcolm applied for and got the job. Malcolm told his children many stories about the Captain and the voyages he made. Malcolm and Ann’s third child, a daughter Mary Ann was born in January 1860 in Stornoway. According to the birth certificate, Malcolm’s occupation was piper on board the revenue cutter Prince Albert. By the time of the 1861 census, the family had returned to live in Hamilton Street, Greenock and Malcolm, now aged 26, was employed as a quay labourer. Ann was now 22, and the children were Angus, three, and Mary, one. Living with them was a boarder, John McFie, aged 27, also a quay labourer, born at Durness on the Isle of Skye. This would have brought in a little extra housekeeping money for Ann but would have added to her workload.

Piping was to be an ever-present feature of Ann’s life. Although Malcolm was no longer employed as a piper, it did not mean that he was not playing.

Greenock was by no means an area devoid of piping. By 1857 Duncan Fraser, who was originally from Beauly, had moved there with his wife and daughters and had a joinery and bagpipe making business in Manse Lane, and nearby, at the Museum Inn was Alexander (Sandy) Cameron, younger brother of Donald Cameron and also from Ross-shire, with his wife and daughter. He had settled in Greenock about 1857, and in 1862, when he won the competition for Former Winners at the Northern Meeting, he was described as Pipe Major of the Greenock Volunteers. The presence of a volunteer pipe band indicates that there must have been other pipers in the town. Malcolm Macpherson would also play with the Volunteers, and while in Greenock, he had tuition from Sandy Cameron. It is possible, too, that Fraser supplied bagpipes to the Greenock Volunteers and Renfrew Volunteers as he is known to have supplied bagpipes for the Dunbartonshire Volunteers across on the north side of the Clyde.

Malcolm competed at the Northern Meeting in 1862, and although he was on the list of entries as Malcolm MacPherson, Piper Renfrew Volunteers, he was not a prize winner that year. Sandy Cameron, PM Greenock Volunteers, won the Champions Gold Medal for Former Winners and also won the Strathspeys and Marches.

Malcolm does not appear in reports of the 1863 meeting, but their second son, John, was born in Greenock later in December 1863.

In 1865 Malcolm’s father, Angus, decided to retire from his position as piper to Cluny MacPherson, and Malcolm took over. The move from town life to an isolated parish in the Highlands must have meant a significant change for the family. It is not known when Ann had left her home on the island of Islay, but after a decade of living in a street of a busy dockside town, the district around Laggan would have seemed quiet, and Ann would have to adapt again to country life.

At the 1865 Northern Meeting, Malcolm placed second and was described as Piper to Cluny. In 1866 he won the Prize Pipe, again being listed as Piper to Cluny.

In 1871 the family lived at Lower Cluny Mains, and Malcolm, aged 36, was employed as a piper. The children were Angus, 13, Mary Ann, 11, John seven, plus three more born after the move to Laggan, Ewen born in December 1866, Norman born in July 1868, and Sarah born in April 1870. Later that year, another daughter, Bertha Maria, was born in November 1871.

In 1876 Malcolm won the Gold Medal at the Argyllshire Gathering. Two more children followed, Angus born in July 1877 and Donald born in November 1880. The oldest boy Angus had gone to Canada before 1877 and died there, so his name was given to the next boy. In these days, when family members emigrated, there was little chance of those at home ever seeing them again, and letters would take a long time in coming. Emigration alone was felt like a loss, and to hear of a death far from home would be felt deeply. Angus, the younger, wrote that he never saw his oldest brother whose name he bore.

This Angus was born to the sound of the bagpipe as his mother told him that while she was giving birth, his father was rehearsing his program for that night’s dinner at the castle. Soon after Angus’s birth, Calum gave up his position as piper to Cluny. The family moved from their cottage near Cluny Castle to a cottage on the other side of the Spey, granted by Cluny to the family in perpetuity. The eldest boy, John, became piper to Cluny, but Malcolm still played on special occasions. According to the 1881 census, his occupation was general labourer, which is rather vague, but at this time, he was earning a living mainly by competing and teaching. The family home was now Catlodge Cottage, a house with four windows. The eldest daughter, Mary Ann, was not with the family in 1881, but maybe Mary Macpherson, unmarried aged 22, born in Greenock, employed as a nurse with the Keith family in Hamilton. Nothing further is known of her.

During these years, we get more insight into the everyday life of Ann and the family. Her son, Angus, included many stories of his childhood in his autobiography. From this, we get glimpses of his mother and a vision of stable and happy family life. We learn that she baked bread for the family and that she kept hens. Gaelic was the predominant language in the family. Malcolm and Ann always conversed in Gaelic, but with the children, they spoke both Gaelic and English to grow up bilingual.

The love of a good mother can never be overestimated and remains with one from the cradle to the grave.

Angus wrote, “Mother had a melodious voice, and often sang to the children the Gaelic songs of her native isle. She had a wonderful ability, untrained, as a sick nurse and was often called upon to help with the needy. In maternity cases, she was reckoned to be most successful, even when in such a wide parish, the medical doctor could not always be at hand. At their bedside, my father and mother always had their Gaelic bible and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress not as a silent ornament but as a guiding star through the years of their lives. The love of a good mother can never be overestimated and remains with one from the cradle to the grave.”

Money was not plentiful in the household. The children attended school, walking three miles each morning, taking with them a noon piece, and walking home again after school. Attendance was not strictly enforced. During the summer months, the children were expected to earn something to supplement the family income. At the age of 10, Angus had his first employment on a farm, and at the end of the six-month agreement,, he received the sum of two pounds, with a day of the farmer’s horses to take home his father’s peats. Angus wrote that it was hard going with a long day, but there was something earned for Mother at the end of six months.

Malcolm made his own pipe bags and made reeds. He taught all his sons to play and possibly the girls too. Angus wrote that his sister Sarah could play as well as any of them. In a small cottage, it isn’t easy to envisage how so many pipers would find room to play. In the summer, they would be able to play outside, but this would be impossible during the dark days of winter. In addition, there were Calum’s pupils who came to the cottage for instruction. Ann took an interest in their progress too. One pupil was John MacDonald, son of Alexander MacDonald piper to MacPherson of Glentruim, a nearby estate. Recalling when John came for the first time, Angus wrote, “My mother who was attentively listening asked of the tutor if Sandy’s boy would make a piper.” Calum replied, “He will make a piper that will be nameable.”

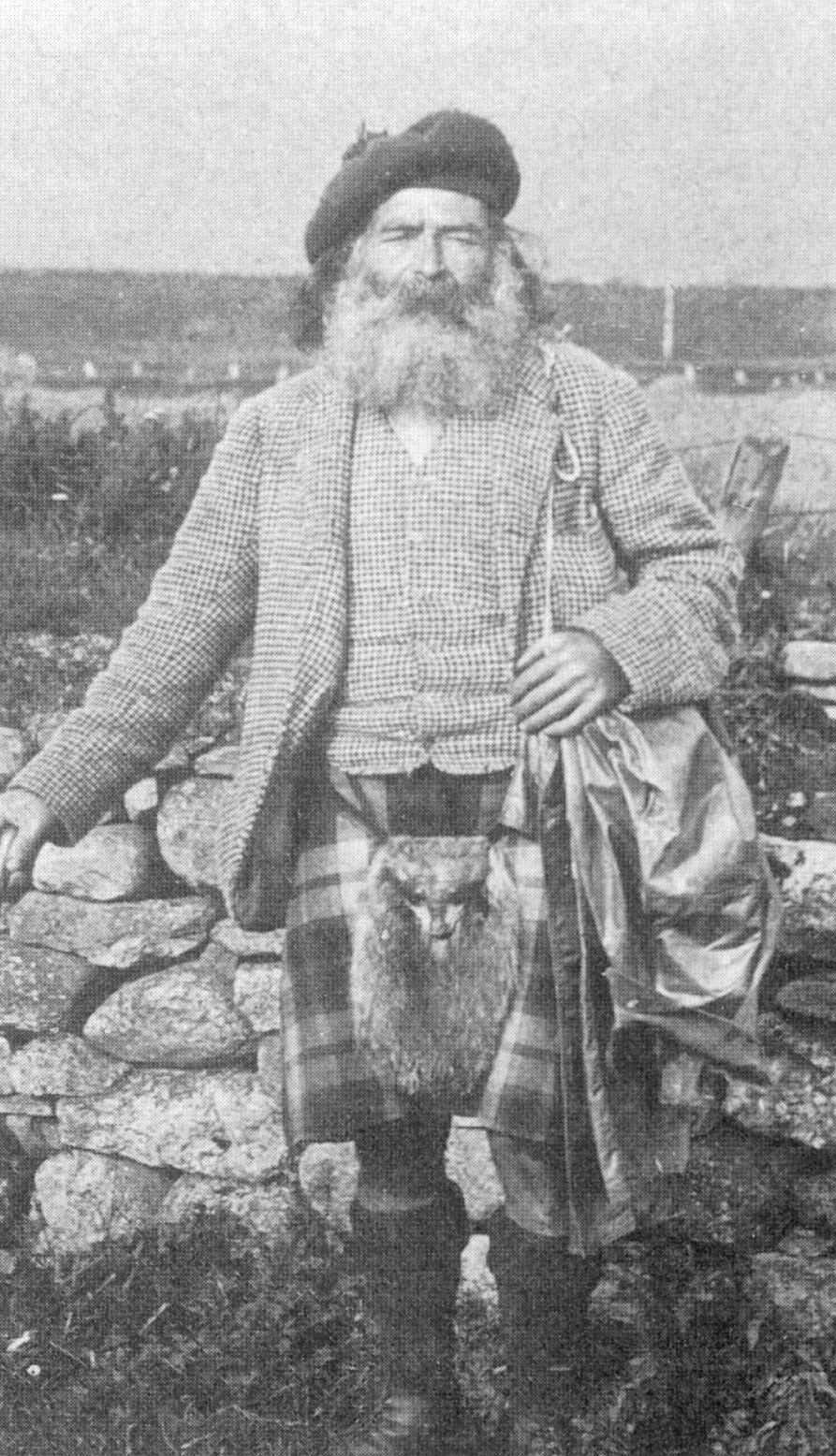

Malcolm was very fit and never ill, but he was troubled with neuralgia. However, he let his hair and beard grow long and was never troubled again.

One can imagine Ann trying to stir the porridge on the fire, feed the children and get them off to school, while Malcolm sat near the fire and played.

John MacDonald recalled Malcolm, with his long curly locks and whiskers, sitting on a stool near the peat fire as he played. He wrote, “Calum played a few jigs on the practice chanter before breakfast. I can see him now, in his old jacket, with his leather sporran, sitting on his stool while the porridge was being brought to the boil. After breakfast, he would take his barrow to the peat moss, cut a turf, and build up the fire with wet peat for the day. He would then sit down beside me, take away all books and pipe music, then sing in his own canntaireachd the ground and the different variations of the particular piobaireachds he wished me to learn.”

One can imagine Ann trying to stir the porridge on the fire, feed the children and get them off to school, while Malcolm sat near the fire and played. It wasn’t just in the morning either. Angus wrote that he and his brothers would lie in bed and listen to their father and his pupils playing pipes. They heard all the great pipers and the tunes. Pupils would walk perhaps eight miles on a winter evening for instruction which might last until the early hours of the morning, then after a cup of tea, walk home again. One wonders if Ann was there to provide the tea and probably something to eat before the pupils left.

Malcolm was often away during the summer. He would walk long distances to play at the Highland games. He would walk from Cluny to Glenelg and then take a boat to Skye to play at the Portree Games, or walk 40 miles to Fort William to compete and walk home again. Sometimes he would walk the seven miles to Dalwhinnie, get a train there, spend a day with the MacDougalls in Aberfeldy, then get the train back and walk the seven miles home in the late evening.

Sometimes he travelled much further afield. In 1886 he went to Edinburgh to play at the Edinburgh Exhibition, where he won two Gold Medals and £10 for each. In 1889 he was one of the pipers invited to participate in the Highland games in Paris, which was part of The Exposition Universelle. This event commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille and featured the official opening of the Eiffel Tower.

It would be quiet at home for Ann and the children when Calum was away; then there would be the excitement of his return, hopefully with medals and prize money, perhaps with presents and certainly with stories of what he had seen and done.

The nearby games were an outing for the family. Angus described a trip to Kingussie Games:

The Games over, the next consideration was our ten-mile walk home. Even after the strenuous day, this did not dampen our enthusiasm in the least. Mother Mo Chridh (mother of my heart) was there, who had already done her ten miles walk to the Games, and she must be brought home in state.

The boys must have had a successful day and received some prize money as Angus continues:

We counted up our drawings for the day and yes, we made up our minds nothing but a hire is good enough for the occasion. But to lessen the expense, all agreed to walk the first three miles to Newtonmore, and there get our conveyance, which we did at the Balavil Inn. Mr. Robert Forbes was the genial proprietor, and ungrudgingly and at a price to meet our meagre purse, he himself with a slow-going white horse and dogcart of rather antiquated appearance drove the gentry the seven miles to Catlodge. As we drove along, we could hear the good old folks, by the way, say: “My word, Benn a Phiobar (the piper’s wife) is doing the grand.”

Malcolm would also play at the local dances where his usual practice would be to open proceedings with a tune on the Great Pipe, then sit down with the bellows pipe and play dance music for hour after hour. Whether Ann went with him on these occasions has not been recorded.

By the time of the 1891 census, Bertha was no longer at home with the family, and her whereabouts are not known. Son Norman was in private service as piper to H. W. H. Dunsmure, at Glenbruaich in Perthshire; Ewen, who played but did not compete, had moved to Glasgow and was working as a hammerman and living in Wilson Street, Partick, with his wife and two children; Malcolm aged 15 was at Cat Lodge Farmhouse as a farm servant.

According to the census, Calum’s occupation was Piper and Ann was listed as Piper’s Wife. Eldest son John is listed as Gentleman’s Servant, unemployed, Angus and Donald are scholars and daughter Sarah is an invalid. Sadly, Sarah died later that year aged only 21.

![The MacPherson homestead at Cat Lodge in recent years. [Photo Jeannie Campbell]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2021/05/Cat_Lodge_Cottage.jpg)

Son Malcolm had a weak chest, so his parents had kept him at home, refusing to allow him to go into private service like his brothers. Eventually, he rebelled, went to Inverness, and enlisted with the Cameron Highlanders. His father tried to get him out but to no avail. He saw action in Egypt and later served throughout the Boer war. Perhaps the sea air of the voyage or the heat of Africa was good for his health.

In 1899 son John was married in London. He had been living there for some time, but after his marriage, he intended to reside permanently in the Highlands, a decision that would surely have given pleasure to his mother.

When the 1901 census was taken, Ann was still living at Cat Lodge Cottage, Laggan, and was described as Housekeeper. With her were her two youngest boys, Angus, 23, and Donald, 20, and for both their occupation was listed as Piper. John and Norman were employed elsewhere, Ewen was in Glasgow and Malcolm was in South Africa fighting the Boer War, which would have been worrying for his mother.

Ann suffered another loss in 1902. Son Ewen died in Glasgow of pneumonia, aged only 35, leaving a wife and three sons.

![The MacPherson gravestone at Laggan Church near Newtonmore, Scotland. [Photo Jeannie Campbell]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2021/05/Calum_MacPherson_Annie_McDiarmid_grave.jpg)

She was buried in the churchyard at Laggan with Calum and Sarah. She did not live to see Angus become the third Gold Medallist in her family.

After her death, the surviving boys scattered around the world. Norman went to Canada in 1906, and Donald followed in 1911, although he moved on to the USA. Malcolm went from South Africa to Australia but later returned to Scotland. Angus travelled widely with Andrew Carnegie and later settled down at Inveran, the namesake of the famous G.S. McLennan reel.

Jeannie Campbell MBE is the world’s authority on the history of bagpipe makers. She is the author of Highland Bagpipe Makers and More Highland Bagpipe Makers, two excellent books on bagpipe makers, and was made a Member of the British Empire in 2014 for her pioneering work and service to piping. With Jim McGillivray, she is co-author of pipes|drums’ ongoing Pipemakers series of historical features on famous bagpipe manufacturers.

Related

Jeannie Campbell receives MBE for Services to Piping

Jeannie Campbell receives MBE for Services to Piping

June 13, 2014

NO COMMENTS YET