The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era: what do we need to learn?

By Ken Maclean

Editor’s note: To date, there have been no scientific studies specific to the Highland bagpipe and pipe bands and the potential spread of COVID-19. With pipe band practices and in-person competitions and performances shut down in most of the world, pipers and drummers are keen to know when it might be safe to get back at it. Some areas of the globe, like Western Australia, have enough confidence to resume in-person events.

The RSPBA’s Chairman, John Hughes, recently asked bands to lobby their members of Scottish parliament to allow pipe bands to return to practice. The move was met by many with derision as irresponsible and even dangerous. Ken Maclean of Sydney, Australia, weighed in on an online discussion with his own research, including an alarming video of the aerosol effects from playing a practice chanter.

We contacted Maclean to gauge his interest in expanding the discussion, and he has kindly provided a detailed four-part discussion of COVID-19 as it pertains to the playing of Highland pipes, the practice chanter, and piping and pipe band performance.

We stress that pipers and drummers should continue to take the utmost care in helping to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

Part 1 – Generic hazards for pipe bands in COVID-19 and need for a collaborative approach

Introduction

Musicians and dancers have experienced enormous personal and professional setbacks throughout the COVID-19 pandemic with enforced isolation, disruption of practice, teaching and competitions as a result of the abrupt cessation of live ensemble performances. This has impacted professional, elite and amateur musicians with a sense of great loss common to all.

Enabling the safe return of piping and pipe bands requires a detailed understanding of the risks for solo and band pipers posed by the instrument itself. Linked to this is the clear need for guidelines for the Highland bagpipe as to its safety and applicable risk mitigation strategies. Many elements will be generic to those for woodwind and brass instruments that will have been created for schools, musical academies, universities and professional musical ensembles such as the those released by the US National Federation of High Schools. The National Federation of High Schools study shows the power of a collaborative approach to the science, policy and practices of music safety in collating the input from over a hundred different musical, scientific and funding organizations.

What needs to be taken seriously in pipe bands is the paradigm shift from understanding COVID-19 as droplet and contact spread disease to an “aerosolized/airborne” disorder as a predominant mode of transmission. This has quickly put vocal, woodwind, brass and traditional mouth-blown reeded instruments such as the Highland bagpipe under the spotlight.

The question arising for the Highland pipes is how the individual hazards from the instrument might pose a risk to an ensemble, the evidence for each element and, summatively, whether the statements of Professor Jason Leith (BBC, “Off the Ball,” June 13) and RSPBA Chairman John Hughes on August 13th truly hold water in asserting the pipes to be safe to play for a socially-distant audience in 2020.

The challenge is how to work together on the answers that are evidence-based and directly applicable to the Highland pipes in order to minimize the risk of disease transmission, to avoid unnecessary restrictions and to prioritize critical interventions.

The aim is to present a series of articles focusing on:

- Generic hazards for pipe bands in COVID-19 and need for a collaborative approach

- The practice chanter

- The Highland pipes

Background

SARS-CoV2 (COVID-19) is a highly contagious 29Kb positive-sense, single strand, linear RNA virus within a fatty “lipid and protein” envelope. It is the seventh identified human coronavirus and is closely related to SARS, MERS and four strains of the common cold viruses.

SARS-CoV2 infection has a case-fatality rate of about 0.2-0.4% depending on the index/at-risk population, i.e., the likelihood that an infected individual will die from the virus. It particularly affects the elderly – leading to bilateral interstitial pneumonitis with respiratory failure in COVID-19 (acute lung infection). The risks in young adults and children is of low prevalence but high impact complications namely acute hyperinflammatory cardiac and vascular diseases, lung disease as well as chronic symptomatology.

Further reading

Profile of a killer: the complex biology powering the coronavirus pandemic

The predominant mode of transmission for SARS-CoV2 in the community has been considered to be droplet spread. There has been a marked paradigm shift such that aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV2 is now understood to be a major mode of transmission. Aerosol transmission is particularly prominent in crowded, poorly ventilated indoor environments as well as aerosol generating procedures – essentially forced exhalation events with singing and with strenuous physical activity, which is applicable to piping in the context of a long practice or blowing a hard reed in the band hall.

There has been much emphasis on surface disinfection to reduce the transmission of SARS-CoV2 by “fomites”‘ – the virus-laden droplets that land on inanimate surfaces and become a source of latent spread to others who come in to direct contact with the contaminated surface or droplet. Spread via the gastrointestinal system is possible but rare for coronaviruses. Both of these modes of transmission may be less important than initially thought, but still essential to mitigate against.

The transmissibility of the virus while initially consider low in school-aged children and adolescents, who are highly represented in pipe bands, has been demonstrated to occur with equivalent viral loads across age groups. Older adolescents and young adults represent a group with a high proportion of asymptomatic or mild clinical presentations with the potential to act as reservoirs for transmission. Asymptomatic spread has been proven with COVID-19, highlighting the importance of adherence to health guidelines.

Generic infectious risks with piping and pipe bands

COVID-19 risks raise a broader question as to the infectious risks among pipers and band members, and the importance of personal and instrument hygiene. COVID-19 risks for drummers are generic and unrelated to their instrument. Known disease causing organisms include influenza and other respiratory viruses, gastrointestinal pathogens, herpesviruses and moulds, fungi and bacterial pathogens. It is the latter group that can arise from within the Highland bagpipe itself.

The condition of bagpiper’s lung is a rare condition associated with the inhalation of fungi and moulds from within the instrument and hyperimmune, allergic responses within the lung in which the body reacts to the continued exposure of these organisms. It is the same condition as seen in brass and woodwind players – a form of hypersensitivity pneumonitis – that can usually be mitigated by simple cleaning measures for the instrument, changes in equipment (e.g., pipe bags) as well as potentially prevented by more recent innovations.

General measures for COVID-19 Safety

The importance of hand washing, hand hygiene and social distancing measures that are universally recommended to reduce COVID-19 transmission is well established. The use of masks is increasingly advocated based on emerging data in high prevalence demographics. Pragmatically, there is an increasing recognition and individual awareness of hand-to-mouth contact and how the simple act of touching one’s face and mouth can lead to disease transmission. This is particularly problematic with piping.

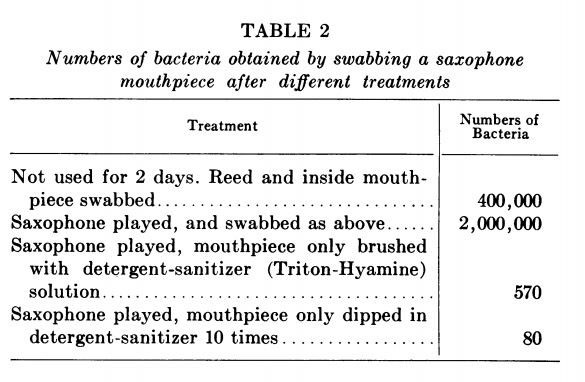

[Image by Dr. Kimberley Prather]

The emerging data: aerosols and COVID-19

The virus, which is about 0.1 microns in diameter, is present within droplets and aerosols. Droplets range from sub-microscopic particles to visible droplets. Flour or dust that can be seen in the sunlight is typically in the order of 100 microns. Droplets typically fall to the ground within 1-2 metres from their source. Droplets contain relatively high viral loads. Aerosols are smaller and lighter, typically between 2-10 microns in size. They dry out rapidly and may become very “virus rich.” Aerosols are able to be dispersed further and to remain in the environment for long periods of time, in the order of minutes to hours. Their small size means that they are more readily inhaled directly into the lung. They are subject to environmental conditions (e.g., sunlight degradation) and are much less problematic outdoors. What constitutes an infectious dose remains a subject of intense scrutiny.

A major concern for piping, as demonstrated by the Washington Choir outbreak, is the potential for a “super-spreading” event. The choir outbreak stemmed from one symptomatic individual, who was estimated to have infected 52 of 61 members of the choir in a two-and-a-half-hour exposure period. The transmission dynamics critical to the event are yet to be fully understood, in determining the relative contributions of droplet spread and aerosolization and how these were augmented by singing. Nevertheless, this and the dissemination via high-intensity indoor gym workouts in Korea provide salutary lessons as the ease of spread of SARS-CoV2.

Further reading

High SARS-CoV-2 Attack Rate Following Exposure at a Choir Practice

Cluster of Coronavirus Disease Associated with Fitness Dance Classes, South Korea

SARS-CoV2 has the added concern that it can survive on various surfaces for extended periods. Recovery of live virus capable of replication is uncommon after 24 hours. SARS-CoV2 is highly susceptible to degradation with soap and water cleaning, disinfectants and exposure to sunlight. Detergents and sanitizers reduce the viral load and disrupting the viral lipid capsule. Disinfectants are more effective in neutralizing virus, and are routinely used for surface decontamination. The choice of disinfectant depends on local guidelines and specific requirements, e.g., laboratories, workplaces, schools, community halls and so on. The Highland bagpipe, being a heritage woodwind instrument, means that the cleaning agents and disinfectants used need to be non-toxic and sympathetic to the instrument. There is emerging evidence that disinfectants may trigger asthma in pre-disposed individuals, meaning that caution needs to be applied in considering their use within an instrument.

Further reading

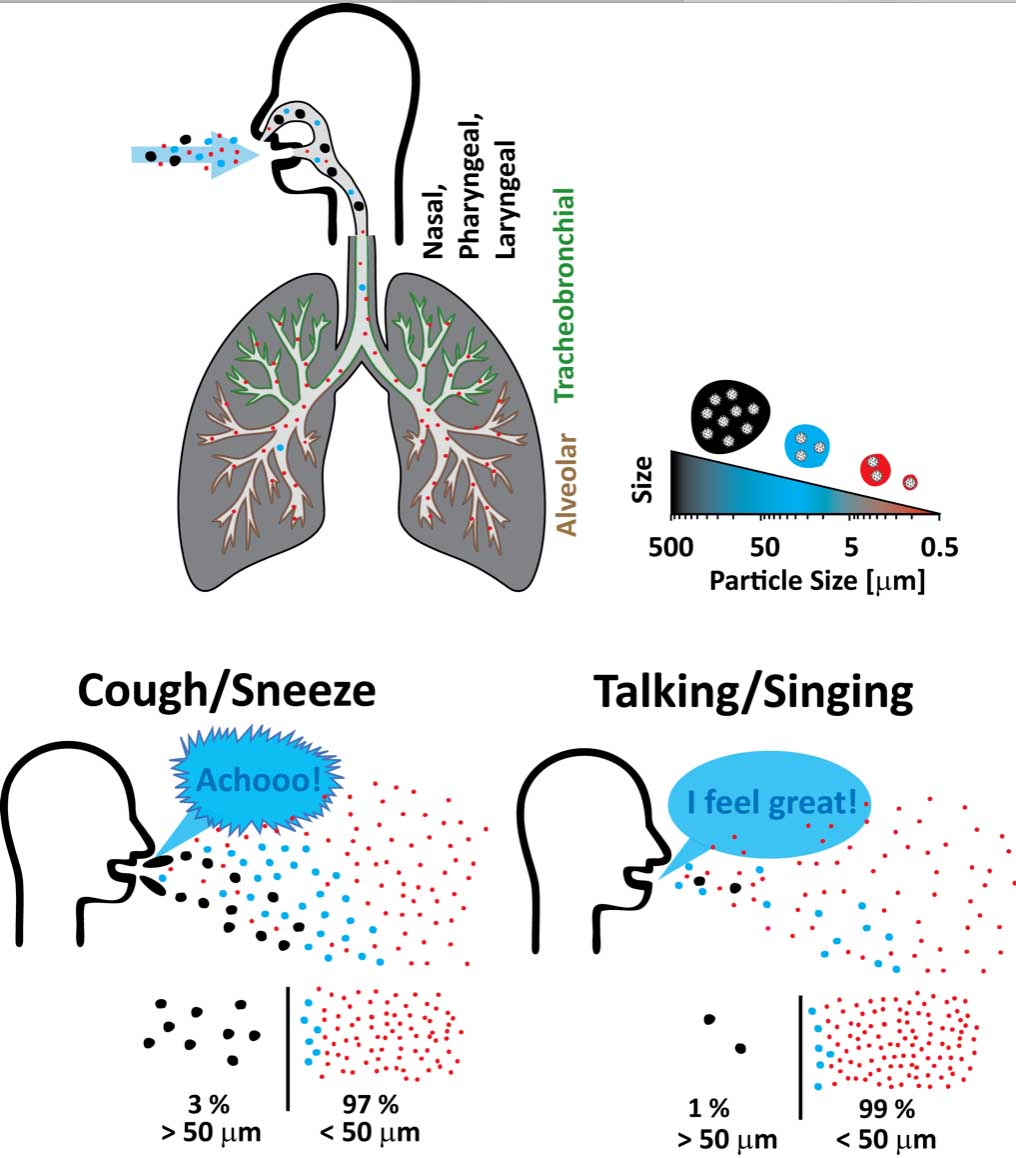

Bacteriological and Cleaning Studies on the Mouthpieces of Musical Instruments

The concept of a “biofilm” is an important one in understanding how pathogens adhere to surfaces, particularly within the instrument itself. A biofilm can be considered as analogous to the seasoning in a pipe bag in that it provides a moist, “protected” environment for pathogens (micro-organisms that cause disease). Physical cleaning measures such as brushes with detergents and sanitizers are important in reducing biofilms and reducing pathogen load (the amount of hazardous material), especially within the mouthpiece in brass instruments, mouthpiece and mouth-blown reeds in woodwinds and blowpipes for the Highland pipes. It is important to do the same within the stocks, reeds, bores and to disinfect or change the pipe bag periodically. The relevance of physical measures for cleaning of the pipes and their importance in hazard reduction for musicians is underscored by studies conducted more than 70 years ago, demonstrating a 1,000 to 10,000-fold reduction in microbial populations with the use of simple, cheap and readily accessible cleaning measures.

[From “Bacteriological and Cleaning Studies on the Mouthpieces of Musical Instruments“]

[From “Bacteriological and Cleaning Studies on the Mouthpieces of Musical Instruments“]

Further reading

Bagpipe lung – a new name for a very old disease

Bagpipe lung; a new type of interstitial lung disease?

Can we quantify the absolute or relative risks?

Traditionally, the risks of transmissible illness in piping have been considered low, such that is has not been commonplace for protective measures, written guidelines or simple cleaning strategies to be in regular use across musical ensembles. Guidelines for musical ensembles in schools as well as community and professional orchestras can be expected to be developed and published in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Determining absolute risks of disease transmission in a musical ensemble is particularly challenging even with local prevalence data. The impression to the musician may be of a randomly changing system, reflecting the stochastic nature of such events. A major determinant of risk to ensembles and pipe bands will be the prevalence of COVID-19 in the community.

In considering the specific risks of COVID-19 transmission among pipers, it is critical to appreciate that the risks go beyond playing the instrument itself. Social distancing needs to be adhered to not only during practice, but before and after the practice. It is influenced by behavioural factors inherent in normal social interactions. Vulnerable individuals will need to consider their particular circumstances. Anyone who is unwell, in close contact with a case, or undergoing testing or tested positive should not attend an in-person practice.

Pragmatically, in outlining risks and hazards in coming articles, the aim is to harness input and expertise rather than to dictate a specific set of guidelines. It is critical that such guidelines take into account the emerging science and that their basis is well understood by the piping community for them to be successfully adopted.

The author would like to acknowledge Bradley Parker for his help with this series.

Stay tuned to pipes|drums for Part 2 of “The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era: what do we need to learn?”

Ken Maclean is a medical specialist in genetics and pediatric medicine based in New South Wales, Australia. His clinical experience means that he has seen firsthand the devastating effects of viral illness in children and families. He is a piper happily enjoying staying safe and improving his piping during the pandemic. Ken has been closely following the literature and community advice on COVID-19 and, in particular, the subject of aerosol science as it pertains to woodwind musicians and ensembles. His goal in giving to back to piping community in the form of up-to-date evidence and science-based advice. He is active on twitter (@kenpcg) and regularly contributes to online discussions of piping safety in the COVID-19 era.

NO COMMENTS YET