The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era: How to pipe through a pandemic

By Ken Maclean and Bradley Parker

Editor’s note: To date, there have been no scientific studies specific to the Highland bagpipe and pipe bands and the potential spread of COVID-19. With pipe band practices and in-person competitions and performances shut down in most of the world, pipers and drummers are keen to know when it might be safe to get back at it. Some areas of the globe, like Western Australia, have enough confidence to resume in-person events. The RSPBA’s Chairman, John Hughes, recently asked bands to lobby their members of Scottish parliament to allow pipe bands to return to practice. Most of the piping and drumming world considered the move as irresponsible and even dangerous, and the Scottish parliament subsequently essentially said No.

Ken Maclean of Sydney, Australia, weighed in on a discussion with his research, including an alarming video of the aerosol effects from playing a practice chanter.

We contacted Maclean to gauge his interest in expanding the discussion. He has kindly provided a detailed four-part discussion of COVID-19 about the playing of Highland pipes, the practice chanter, and piping and pipe band performance.

We stress that pipers and drummers should continue to take the utmost care to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

Part 3: How to pipe through a pandemic

Introduction

This final article focuses on the bagpipe and the hazards associated with playing and handling the instrument in the era of COVID-19. It is predicated on the information contained in Part 1 and Part 2 that highlights generic hazards, the governance framework and the practice chanter, respectively. A central tenet is the merit of the key piping institutions harnessing community contributions and expertise for funded research on COVID-19 risks for the Highland bagpipe and to develop consensus guidelines for effective risk-mitigation strategies.

The simple goal for pipers and pipe bands in 2020-’21 is to practice safely, play and perform as an individual and within an ensemble. The hope is to play individually or in a band in front of a tutor, fellow musicians, the general public and ideally, in an adjudicated contest with a live audience. The paramount aim is to avoid viral transmission and, more particularly, to ensure that the Highland pipes and pipe bands are not central to a super-spreading event, such as might occur at a practice, concert or competition.

A critical assumption is that community transmission is sufficiently low to allow safe congregation, as per local guidelines. Two of the leading examples of effective suppression strategies with sustained zero community transmission are Western Australia and New Zealand, underpinning the return of competitions in those regions.

Pragmatically, the questions pertain to relative risks. A zero-risk face-to-face environment is unachievable. The aim is to bring risks to an “acceptably low risk.” The choice to participate is one that individuals, bands and organizations need to consider and decide upon.

This article canvasses the questions that need to be answered by the best available evidence rather than presenting a didactic set of guidelines that might be considered opinion-based. According to the changes in evidence and expert advisory guidelines, guidelines should be consensus-based and subject to regular review.

Where is best to play the pipes, and why?

Recent data have highlighted the extent of viral transmission via aerosols in addition to the larger “ballistic” droplets and fomites that are directly relevant to potential viral (COVID) spread from the Highland pipes as a moisture-laden musical instrument.

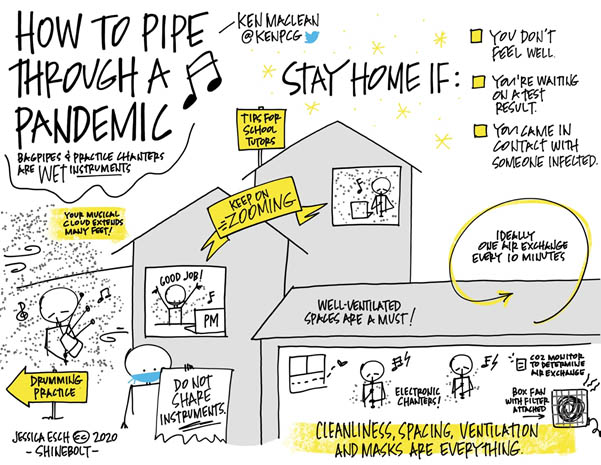

Aerosol scientists have focused our attention on environmental factors and risk stratification. Practically, this translates to the environment in which pipe practice is occurring. The risks are different for indoor, covered and open-air outdoor environments. In order, they are:

- Outdoors with hand hygiene, masks & spacing

- Outdoors and undercover with hand hygiene, masks & spacing

- Indoors w effective cross-ventilation (a/a + windows & doors open, cross-breeze)

- Indoor with poor ventilation (NB/may include a windless day)

- Space, hand hygiene and masks alone

- Space + hand hygiene only

- No protective measures

Indoor environments require musicians, schools and tutors to consider:

- Room size (e.g., a school music teaching room vs a band or concert hall).

- Room ventilation that may be assessed via CO2 monitoring.

- Air exchange (air changes per hour – six air changes per hour is considered a safe industry standard).

- Heating ventilation, air conditioning (HVAC) systems; particle filters (MERV13, HEPA); UV germicidal irradiation systems for air purification to inactivate pathogens.

Further reading: Coronavirus prevention with air filters: understanding MERV and HEPA

- Effectiveness and placement of fans to maximize air exchange, not just dispersal.

- Social distancing (proximity/spacing).

- Duration of exposures (duration of practice sessions, intervals to allow for air changes per hour).

- Person protective equipment for:

- Source suppression, e.g., players wearing a surgical mask w a hole for the blowpipe.

- Protection – masks, face shields and glasses – as the last line of defense.

Aerosol data favours masks over face-shields.

“A musical cloud”

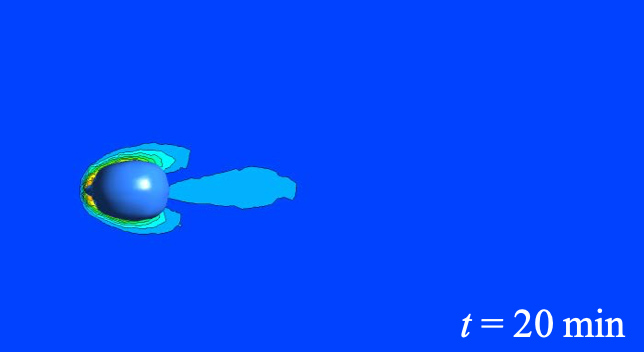

The question of a “personal cloud” for a piper or indeed for any woodwind or brass musician is one that warrants further consideration. Usually, an individual has a personal cloud consisting of expired air, volatile organic compounds, etc. that tend to collect immediately around the face and extend in flare-up to ~1-2 feet behind a person’s head. This idea can readily be extended for a musician and individualized for their instrument based on aerosol visualization data, e.g., Schlieren testing. This approach allows for individual musicians to be modelled into ensemble settings.

“Head cloud” taken from nfhs.org, Dr. Shelly Miller @ShellyMBoulder

These individual “musical clouds” likely merge into a single larger cloud within the room in a relatively short space of time. It is the time to aggregation into a single cloud – that is presently unknown – that might dictate a safe duration for practice in an indoor environment before allowing for near-complete air exchange to allow further ensemble practice.

Determining the size of an individual musical cloud may be necessary for spacing with outdoor practices or practices in covered areas and along with the duration of exposure, number of pipers and interval required for air exchange.

Moisture control systems as a trigger for cleanliness and hand-hygiene

Until very recently, moisture control systems all needed to be within the bag and stocks. Moisture control systems pose a particular “fomite” hazard with the need to handle the instrument’s interior with zippered bags. It highlights why hand-sanitizer should be within every piper’s instrument case, along with a fresh towel and paper toweling. Internal moisture control systems highlight the importance of reframing setting up at the start of a practice to “switch on” to instrument hygiene and peer safety. This focus needs to continue to the end of any ensemble practice.

“The question of whether moisture control systems can aid return to ensemble practice is an important one.”

There is the potential that a recent innovation that moves the moisture control system into the blowpipe – the Flux™ blowpipe – may significantly reduce the amount of moisture entering the bag. Retaining more of the moisture within the blowpipe aids hygiene and cleanliness. The blowpipe is a critical discussion and one that warrants a separate article that considers various moisture control systems available, average airflow in and out of the Highland bagpipe with playing, and how keeping a bag drying impacts on the risk of aerosol transmission, fomite/contact transfer as well as the “hygiene” of the Highland bagpipe. The question of whether moisture control systems can aid return to ensemble practice is an important one. If proven helpful, it could form the basis of strategies for other woodwind instruments.

Addressing fomite transfer echoes the broader question of cleanliness and instrument hygiene in setting up, opening up and packing away the instrument. This responsibility is to our peers, and indeed, we may come into contact with all of the people during and after practice to all of the people with whom we may come into contact. Pragmatically, the pipe case’s interior, the various accoutrements and the pipes, bag and reeds should all be considered unclean/potentially infected and in the “red zone” for risk. Even the outside of the instrument with the constant handling quickly becomes “contaminated.”

Cleaning and simple maintenance should, where possible, occur outside of the band room as a regular brief task before and after each practice. There are commercial disinfectants that can be safely applied to the instrument and its reeds and simple cleaning strategies that use everyday household items, e.g., soap and water. While sweat is not a known source of transmission for COVID-19, the hand-to-face and use of towels may spread secretions, so hand hygiene is important when “toweling off” at the break following a set or sets.

Schools

A significant concern for all pipers, bands and governing bodies is the foreseeable loss of a generation of aspiring pipers with stringent restrictions currently in place for school and youth bands. Restrictions can be formal – by way of government mandates on school woodwind, brass, choirs and traditional music ensembles that include piping, via community-driven based on precautionary measures and local advice or, by the withdrawal of learners and young pipers.

It is essential to acknowledge the work of youth band and school tutors and the extraordinary efforts made by music advocates, school music teachers, pipe-majors and piping tutors in 2020.

The return to school in Scotland – of which there are more than 5,000 – has seen many school pipe bands adopt weekly Zoom lessons from the start of term one. These online meetings need to provide for 15-20 learners, all of the various grades, all having one-on-one 30-40 minute online lessons using traditional mouth-blown chanters. It requires considerable organizational efforts, adaption to technology and predictability, comes with both pros and cons for the teacher, student and school. The loss of the face-to-face elements can be replaced only to a certain extent and is quickly undervalued. While online platforms work well for one-on-one chanter practice with school band members, it loses the subtle appreciations, insights and experiences of playing face-to-face. It misses entirely on the ensemble aspect, the peer-to-peer learning and the essential nature of social engagement with peers and mentors, leading to continued involvement at an introductory and experienced level. Based on feedback from both returning and non-returning players term-to-term, it remains to be seen how the students perceive it.

“Knowledge-sharing and pathways for this will be vital for tutors and students for each stage of their learning.”

Online teaching for school bands poses a particular challenge in transitioning learners onto the bagpipe and helping those already on the pipes to set up and maintain their instrument. These are challenges for which it will be essential to share knowledge on practical approaches and potentially novel strategies to counter these problems. Knowledge-sharing and pathways for this will be vital for tutors and students for each stage of their learning.

Maintaining the base of learners, young pipers, and school bands that can progress smoothly from absolute beginners to novices to becoming accomplished musicians is paramount. To this end, we need to anticipate that schools, parents, students and tutors will want to have clear guidance on the safe face-to-face teaching of piping, bagpipe maintenance and pipe band practice as the students search for the inherent challenges and joy of progressing in their piping.

Considering how best to continue to teach our students should be a goal that unites all pipers, drummers and pipe band enthusiasts in 2020.

Ken Maclean is a medical specialist in genetics and pediatric medicine based in New South Wales, Australia. His clinical experience means that he has seen firsthand the devastating effects of viral illness in children and families. He is a piper happily enjoying staying safe and improving his piping during the pandemic. Ken has been closely following the literature and community advice on COVID-19 and, in particular, the subject of aerosol science as it pertains to woodwind musicians and ensembles. His goal in giving to back to the piping community in the form of up-to-date evidence and science-based advice. He is active on twitter (@kenpcg) and regularly contributes to online discussions of piping safety in the COVID-19 era.

Bradley Parker is from from Portavogie, Northern Ireland, and at age 24 already has had a successful solo piping career and six years as a piper with Grade 1 Field Marshal Montgomery, winning three World Championships in that time. He recently achieved a BMus in Traditional Music (Piping) from the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland.

Related

The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era: what do we need to learn?

The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era: what do we need to learn?

August 31, 2020

The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era: what are the COVID-19 risks, and how can we reduce them?

The Highland bagpipe in the COVID-19 era: what are the COVID-19 risks, and how can we reduce them?

September 5, 2020

![]() RSPBA advocates for pipe band exception to COVID-19 restrictions

RSPBA advocates for pipe band exception to COVID-19 restrictions

August 16, 2020

NO COMMENTS YET