The complexity and risks of playing the music we love – Part 2

In Part 1, Liz Sheridan discussed her symptoms and her road to diagnosis. In Part 2, she takes us through her treatment and makes suggestions for learning more about similar difficulties if you also suspect you might suffer from more complicated dexterity problems.

The complexity and risks of playing the music we love – Part 2

By Liz Sheridan

The ambiguity of troubleshooting

Due to the complexity of factors that need to combine for playing an instrument to go well, it can therefore be equally difficult to diagnose and solve when things aren’t going well.

I personally didn’t understand the root of my hand issues for seven years, due to several contributing factors.

As a musician, I defaulted to the areas within my control and assumed that the spots that felt “off” just needed to be picked apart more. A degree of the awkwardness while playing seemed due to muscle memory, as my mind had learned to anticipate note sequences that experienced discomfort/lack of control during the summer my dexterity was declining.

I went back to the basics of picking apart sequences and mentally re-taught my hands to play certain movements (mainly, going from the top hand down with a G gracenote on the lower note). I did experience positive changes, but several years into problem solving felt my improvements had plateaued – there was still a residual discomfort left in my hand. My movements were 80 or 90% back to normal, but it felt like there was a ceiling to having full freedom of playing (which I now realize was due to the remaining physical limitation).

Adding to the ambiguity, the onset of repetitive strain injuries can be very subtle and gradual. In my case, it wasn’t obvious whether I had a physical restriction even years after working to retrain my muscle memory.

It’s probably safe to say that every player experiences strengths and weaknesses in their playing and therefore learns to dissect the tricky spots and select music to highlight their strengths. It’s therefore not always clear cut as to what a common weakness is vs a potentially lurking factor/injury that’s limiting improvement.

Adding to the ambiguity, the onset of repetitive strain injuries can be very subtle and gradual. In my case, it wasn’t obvious whether I had a physical restriction even years after working to retrain my muscle memory. Now that I’ve completed the surgery and glimpsed the feeling of free nerve movement, I even wonder if some of the “sticky spots” that started in my earlier years of playing were perhaps due to the early beginnings of nerve compression.

In addition, health practitioners may not be familiar with the unique demands of an instrument.

“Many clinicians and healthcare practitioners treating upper extremity injuries are not familiar with the specific demands faced by instrumental musicians and how to tailor treatment and prevention strategies to the specific risks and occupational needs of each instrumental group.” [4]

The nature of repetitive strain injuries may not be obvious, so it may take self-advocacy or a perceptive healthcare professional to recognize an injury proactively. I unfortunately experienced this when I raised my hand concerns with my doctor in the months the symptoms first appeared, but no further steps or diagnostics took place. Due to not personally knowing whether the root of my “sticky spots” while playing were physical or mental, I didn’t seek further diagnostics via my primary healthcare provider until years later when the symptoms worsened.

The risks of playing an instrument

I always knew in theory that the Highland pipes aren’t ideally ergonomic, but repetitive strain injuries in the piping world are more common than I realized.

My discussions with other pipers and drummers over these years have revealed that I’m not alone in my experience. Some players have lower back pain from carrying the weight of a drum, numbness of their whole arm by the end of a piobaireachd, a trigger finger (stuck in one position), focal dystonia (cramps, spasms, loss of muscular control), tendonitis/tendonosis (swelling/pain/etc. due to inflamed tendons), carpal tunnel syndrome (tingling, numbness, weakness of the median nerve), as well as other cases of cubital tunnel syndrome.

The following excerpts from an academic research paper in the Journal of Hand Therapy, demonstrate this experience is pervasive beyond Highland instruments.

“Performance related musculoskeletal disorders (PRMD) are common in instrumental musicians and often affect the upper extremities. These overuse injuries typically result from inadequate attention to the musculoskeletal demands required for the high-level performance of musician-students and experienced instrumentalists. PRMDs often interfere with career trajectory, and in extreme cases, can be career ending.” [4]

The risks faced by all musicians:

“General risks affecting all instrumental musicians include repetitive and non-ergonomic movements over extended periods of time that can result in overuse and tightness of specific muscles and underuse or weakness of other muscles. These risks may be further exacerbated by sudden changes to practice schedules, repertoire, and technique in response to career shifts, upcoming performances, or auditions. Musical instruments demand complex hand movements and at times awkward postures due to their specific shape and weight. Some instruments are more asymmetrical than others.” [4]

The biomechanics of wind instruments:

“Woodwinds and brass instruments vary greatly in size and shape. Instruments are supported using the upper body, with asymmetric demands, especially of the right hand and thumb. The weight of the instrument can be a contributing factor to PRMD if not balanced properly or held for prolonged periods of time. Harnesses and neck straps relieve weight from the upper extremities of the performer and are frequently used by bassoon and contrabassoon players…. Wind instruments require all 10 fingers to operate keys or cover holes. Wide hand spans are often necessary to play some of the higher and lower notes or to cover the complex multi-digit motions to play notes separated from another on the scale. [4]

Common pathologies for wind instruments:

“Wrist and thumb pain is a common finding in wind instruments due to the weight of the instrument. The effects of overuse are seen in the first web space of the right hand and ligaments at the base of thumb and radial side of the wrist, likely due to the position of the hand supporting the instrument while playing. Tenosynovitis of the first dorsal compartment (De Quervains tenosynovitis) and of the flexor tendons is common. Bilateral thoracic outlet-like symptoms are also seen, as well as ulnar nerve compression on the left side. Brass players overall have lower reported rates of PRMDs. The reason for this is that they typically have less playing time, and the embouchure muscles and lips require frequent breaks during playing. However, they do suffer musculoskeletal problems linked to lip muscle. Nerve irritation and compression is reported in the upper extremities, with compression of the median nerve at or distal to the wrist (carpal tunnel syndrome), and thumb digital nerve irritation from the weight of the instrument.” [4]

The biomechanics of percussion instruments:

“Percussion spans a wide range of instruments, techniques, and styles in some cases with symmetric and other asymmetric upper limb demands. … Percussionists use sticks, mallets, and bare hands to strike various instruments rapidly and often forcefully. This movement results in rapid deceleration of the fingers and wrists upon contact with the instrument, transmitting the impulse up the hand and arm. Repeated movements in this manner oftentimes lead to trauma of the muscle-tendon units and inflammation of the tendon sheaths.” [4]

Common pathologies relevant to pipe band drumming,

“Up to two-thirds of percussionists have been reported to have musculoskeletal pain, mainly from tenosynovitis and/or arthritis in bilateral hands and wrists” … “An electronic survey from drummers from 49 different countries, encompassing a broad spectrum of ages, career stages, experience levels, and musical genres, showed that out of 831 respondents, the most commonly affected body region was the upper limb, and the most affected anatomical locations were the wrist joint (25%) and low back (24%). Analysis of diagnoses reported yielded main response categories: inflammatory conditions (e.g., tendinitis); neuropathies (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome); back and spine (e.g., intervertebral disc problems); muscle and tendon problems, non-inflammatory (e.g., muscle spasms/strains/fatigue); and other diagnoses.” [4]

Seemingly a common ailment among pipers and drummers, my post-surgery Occupational Therapist (specialized in the Acute Hand Program) provided additional clarification on the difference between a tendonitis and a tendonosis:

“Tendonitis is the acute presentation of inflammation due to the overloading of a musculotendinous unit and frequently presents with symptoms of swelling, pain, etc. When these symptoms go untreated for prolonged periods of time, the acuity morphs into a chronic state. Thus, the chronic presentation of a tendonitis is a tendonosis. A tendonosis is characterized by chronically damaged tendons whereby under a microscope the tendon fibres look completely different from a healthy tendon: thick/increased scarring/etc. A tendonosis implies that the damage has been sustained for a long period of time, that the tendon hasn’t had a chance to rest or heal, and that degenerative changes are imminent. Repetitive strain injuries in musicians, that are long standing, will most likely be a tendonosis.” [5]

The bottom line

Pipers and drummers and committed players of any type of instrument or activity with repetitive motion are prone to overuse injuries. Fortunately, many music teachers and teaching programs emphasize the importance of good posture, hand positioning, and instrument set up. However, even with strong fundamentals and an awareness of/attention to these areas, overuse injuries can still occur. I would hazard a guess that these types of injuries, or even subtle impacts to playing without the player realizing it, are much more prevalent in the piping and drumming community than we know.

Treatment and prevention strategies

“Harnesses and straps are effective in transferring instrument weight proximally from the hands and forearm to the shoulders. Stand supports and posts are also effective in weight distribution. Playing orthoses may be used to support the instrument by transferring part of the instrument to a more proximal joint or muscle group. Education in proper posture with special attention to placement of the music stand at eye level is important to avoid head and neck rotation. Gel caps and sleeves can be used to protect irritated digital nerves and aid in proper weight distribution. Again, symptoms of progressive numbness or weakness should be evaluated by a physician.” [4]

Due to the many factors that contribute to healthy, free flowing movement, the identification and treatment of ailments should be personalized to the person and instrument.

As recommended by my post-surgery Occupational Therapist (specialized in the Acute Hand Program):

Anyone that presents with an upper extremity acute injury / repetitive strain / chronic symptoms would do well to look for a registered occupational therapist or physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of hand and/or upper extremity conditions, to assess and provide treatment.

The Canadian Society of Hand Therapy (CSHT) has a website with a “Find a Therapist” option (right across Canada). It is a fabulous resource for athletes, musicians and regular folks who are looking for specialized treatment.

In the US, the American Society of Hand Therapy (ASHT) has a similar mandate.[5]

Additionally, the International Federation of Societies for Hand Therapy (IFSHT) aims to facilitate the communication between hand therapy societies and individual hand therapists all over the world (which also includes a “Find a Therapist” option with a global list of member country societies).

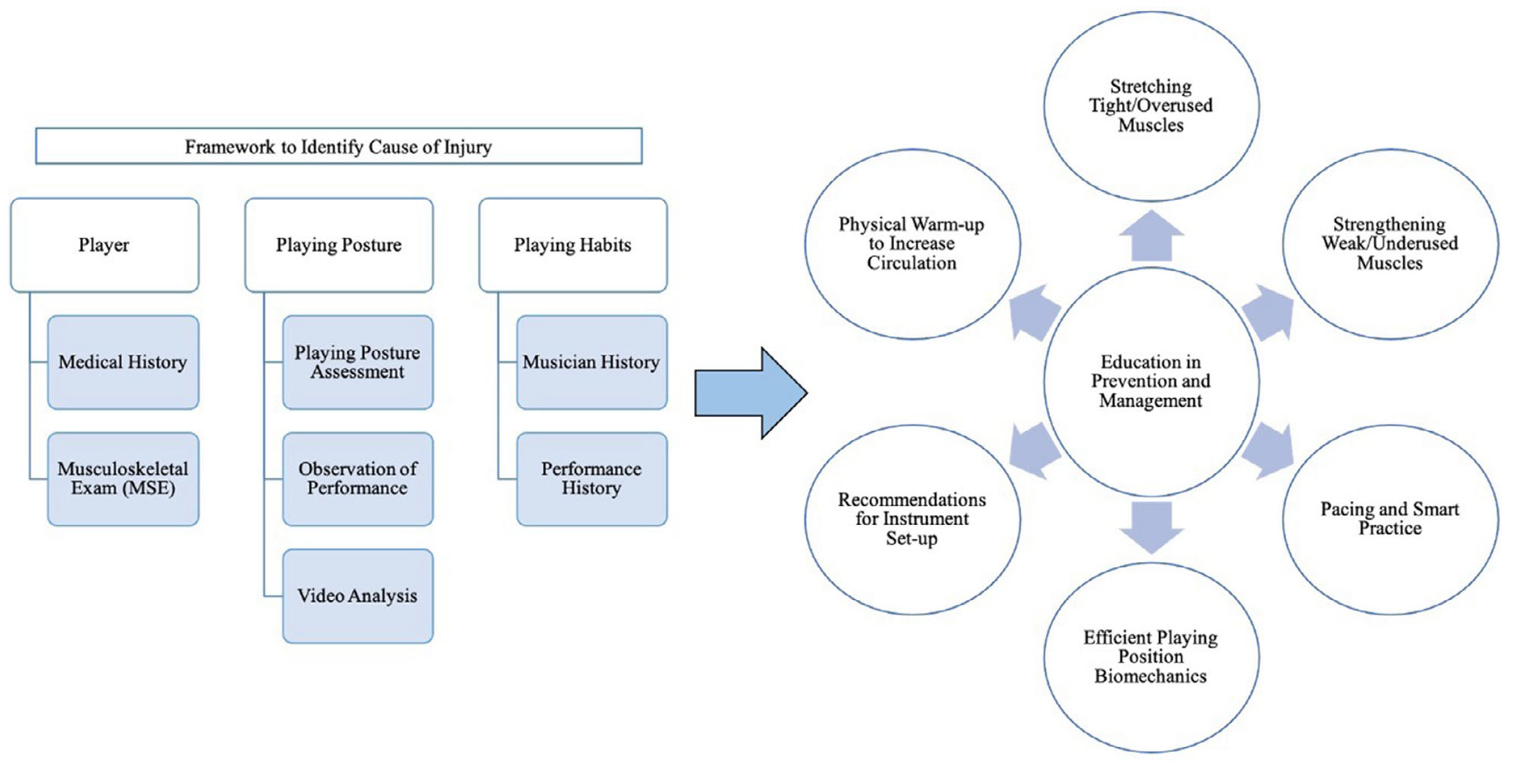

The above-mentioned journal article proposes a framework to assist clinicians in the prevention, assessment, and treatment of performance related musculoskeletal disorders in musicians:

Musician-centered approach for identifying causes of injury (left) and treating PRMDs using education, prevention, and management (right). [4]

In my own situation, I’ve reflected on the contributing factors and how my experience will influence my approach to playing bagpipes, other activities, and seeking answers to my health in general moving forward.

- Listen to your body – proactive awareness of positioning, comfort, ergonomics, and any feelings of strain while playing. Especially after an adjustment is made to the instrument, like a new pipe bag. It’s not always obvious or sudden if something is going wrong, so be mindful of how things feel.

- Awareness of risks and complexities – if issues do creep in, look at it from all angles. Perhaps it’s a common muscle memory spot or perhaps there’s another factor that could worsen. Try to be aware of all the possible causes and if you suspect a deeper cause, don’t play through the discomfort, make a change and keep seeking answers.

- Advocate for answers – if you suspect you’re experiencing a physical limitation, advocate for a medical diagnosis and let that guide your treatment plan. This may need to include self-advocacy or educating your clinician on specifics of the instrument. As my doctor initially didn’t initiate any diagnostics/next steps, I sought a solution via physiotherapists, chiropractors, and other professionals who treat pain and injuries. In many cases, this route could proactively and successfully treat the symptoms. However, there’s a risk to treating the symptoms if the root cause is not fully understood, including lost time/money or potentially further damage to an injury (i.e., in my case, deep tissue massage on my elbow may have contributed to a faster decline / more severe nerve compression). If possible, try to find clarity on the issue itself, which could lead to a faster solution and/or better management of the impacts.

- Connect with the community – reach out to the community and take advantage of the diverse ideas and experiences of those in the piping and drumming world. I was able to set up a zoom call with a piper who had been through the same nerve surgery and recovery, which helped set my expectations before and after the procedure. Connecting with other pipers and drummers to share experiences is a powerful opportunity we have in the Highland community.

- Self-compassion – be patient with yourself and the process of healing / improving as a musician. I had the initial expectation of fixing my hand issues as quickly as they seemed to onset (four months). A quick answer or solution may not be feasible, so try to appreciate the journey of the instrument rather than a destination (which may be out of your control to reach).

- Find your motivation and hang onto your joy – when dealing with challenges while playing the instrument, try to hold onto the reasons you love playing despite the frustrations. Maybe there’s a way to reframe the hurdle or reset the expectations of yourself to ensure you’re still gaining energy and enjoyment from playing rather than feeling drained by the ups and downs.

Final thoughts

At a Piping Live! event during my 2013 Scotland trip, I remember learning of a prominent piper who recently had nerve surgery on their left elbow. Even though I was in the same room as them, it never occurred to me that I could be at the very beginning of that same journey. Maybe it was denial, more likely it was naivety. At the time, I assumed we’d find the quick fix and I’d be back to my usual playing in a couple of months. A few months later it sunk in that it may take longer than expected and two years later it truly sunk in that my piping path wasn’t returning to where I hoped it would.

I’ve experienced a form of grief over these years, not for the loss of finger dexterity that barely impacted me day-to-day, but grief for the player I had always hoped I could become.

I’ve experienced a form of grief over these years, not for the loss of finger dexterity that barely impacted me day-to-day, but grief for the player I had always hoped I could become. Based on the clarity I have now, I sometimes wonder what in my life would be different had I managed to prevent or solve the worsening of my symptoms sooner. Now that nine years have passed (including four years since I’ve played), my mindset and some areas of life have evolved without having piping as incorporated. Time will tell where my arm healing process (physically and emotionally) will take me.

During the early days of my arm issue, my sister gifted me the print below. The “success is a journey, not a destination” quote still stands true today – from not understanding the issue for many years, to then letting go of my playing goals and a part of my identity, and finally finding clarity and potentially regaining hope for a solution. The highs and lows of my piping journey have contributed to who I am as a person. I’m grateful for the life lessons, memories, and lifelong friends.

Liz Sheridan is a Professional-grade solo piper who has also competed at the Grade 1 band level with the Peel Regional Police and 78th Highlanders (Halifax Citadel). In 2012, she finished a five-year double degree program (two simultaneous undergrads) in Business at Wilfrid Laurier University and Mathematics at the University of Waterloo, both in Waterloo, Ontario, and now works in HR Analytics/Technology with a healthcare marketing agency. She has been on a four-year break from competition, but recently completed her B-level band and solo adjudication exams with the PPBSO. She hopes to stay involved in the piping community and eventually return to playing when her remaining finger issue is resolved.

References

- Diagram adapted based on: “Introduction to Physiology of Human and Physiology of Exercise.” Introduction to Physiology of Human and Physiology of Exercise, Faculty of Sports Studies Masaryk University, https://www.fsps.muni.cz/emuni/data/reader/book-4/02.html.

- Clip art photo from: “Vector Illustration of an Irish Marching Band in Silhouette Form.” IStock, https://www.istockphoto.com/vector/irish-marching-band-gm472345129-26188865.

- Green, Barry, and W. Timothy Gallwey. The Inner Game of Music: Overcome Obstacles, Improve Concentration and Reduce Nervousness to Reach a New Level of Musical Performance. Pan Books, Pan Macmillan, 2015.

- Yang, D.T. Fufa and A.L. Wolff, A musician-centered approach to management of performance-related upper musculoskeletal injuries, Journal of Hand Therapy, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2021.04.006.

Occupational Therapist – Acute Hand Program, Halton Healthcare.

NO COMMENTS YET