The complexity and risks of playing the music we love – Part 1

Editor’s note: Ten years ago, Liz Sheridan of Oakville, Ontario, was on a rapid ascent as one of the world’s most promising solo pipers. After promotion to Professional by the Pipers & Pipe Band Society of Ontario, she was scooping up prizes in the top grade until she encountered difficulties with her dexterity. Over the following decade, she has sought out a diagnosis of and possible solutions for her difficulties. After many years, she gradually returned to playing and hopes to regain the full prowess she once enjoyed. Liz Sheridan kindly offered to share her story and her suggestions for the many pipers and drummers who might be experiencing similar struggles.

The complexity and risks of playing the music we love – Part 1

By Liz Sheridan

Piping and drumming are all-encompassing hobbies for many players worldwide. Playing a Highland instrument provides an outlet for self-expression, exposure to cultural history, refines listening and memory skills, increases memory capacity, and creates a connection to a worldwide community. Learning and refining an instrument also takes discipline, time management, patience, perseverance, and may come with ups and downs. While many factors that lead to success are within our control, there’s also an element of ambiguity when dealing with the complexity of an instrument coupled with the mental and physical demands of playing.

Piping and drumming are all-encompassing hobbies for many players worldwide. Playing a Highland instrument provides an outlet for self-expression, exposure to cultural history, refines listening and memory skills, increases memory capacity, and creates a connection to a worldwide community. Learning and refining an instrument also takes discipline, time management, patience, perseverance, and may come with ups and downs. While many factors that lead to success are within our control, there’s also an element of ambiguity when dealing with the complexity of an instrument coupled with the mental and physical demands of playing.

This article aims to share my own experience as a piper encountering obstacles along the musical journey. After nine years of misunderstood lessened-dexterity in my left hand, I was diagnosed with Cubital Tunnel Syndrome (compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow) and underwent a surgery that will prolong and hopefully improve my ability to play.

Should I just play through it? Is this all in my head? Do I need to change my instrument set up? Is it me or is it the bag? Increasing awareness of the risks may help musicians to proactively mitigate for overuse injuries. However, it’s not always clear cut how to troubleshoot our “sticky spots” – there’s a nuance to understanding and improving movement.

Whether you are experiencing physical hurdles or not, we all go through the ups and downs and ongoing analysis of our playing when striving for improvement. I hope my experience will be relatable to all players/instruments and may spark ideas on how to understand the obstacles we face on the non-linear path of trying to improve as a musician.

Disclaimer: I’m writing this from the perspective of a piper and patient. I’m vastly underqualified to discuss medical topics, so if you are experiencing a hurdle that you suspect may be physically or psychologically related, please reach out to a medical professional. The scope of this article is constrained to my own learnings and interpretation of these topics. I’ve encountered anecdotal experiences and academic research that relate to this theme, and feel I’ve only scratched the surface of the depth of information, expertise, and resources that exist.

My story

I began to learn the pipes in 2003 and was fortunate to have the support and resources to move up through the competitive grades in Ontario. In May 2013, during my fourth year in Professional solos, my pipes weren’t feeling comfortable after switching pipe bags. The competition season was just beginning, so I kept playing through the awkwardness alongside trying to troubleshoot. I adjusted as many variables as I could think of (blowpipe angle/length, chanter angle/height, distance of drones to shoulder, etc.), but playing gradually became more uncomfortable and eventually impacted my arm on and off the instrument.

In August 2013, I flew to Scotland with my mom for a series of Highland games, culminating in the Silver Medals at Oban and Inverness. During the first week overseas, I switched to a new pipe bag hoping it would be the solution, but unfortunately didn’t experience any improvement. The awkwardness while playing had turned into dull pain, twinges, and a loss of dexterity in my left hand (with my hand slipping off the chanter entirely at times). We decided to go to a walk-in clinic. The medical staff suspected it was tendonitis, which came with the recommendation to take a break from playing and ice my arm daily. It was very unnerving to be in Scotland, days away from the biggest solo events of my piping career, and not playing.

I did get back to practicing a few days before Oban and the night before the Silver Medal, I strangely didn’t have butterflies. The thrill of competition – the excitement of knowing I could potentially play my best and see where things fall – was missing. My goal in the Silver Medals that year was simply to keep both hands on the chanter and not break down, and I wasn’t entirely sure that was in my control to achieve. I fortunately did make it through my tunes at Oban and Inverness, with several mishaps, but I was relieved knowing that it could have been much worse.

I couldn’t tell if it was due to muscle memory vs. physical and eventually, and the emotional rollercoaster took its toll.

When we returned home, I went into full problem-solving mode. I tried new pipe bags, retrained my muscle memory (re-learning G gracenotes from the top hand down, finding mental tricks to hide the awkward spots, etc.). I saw my doctor, physical therapists (physiotherapists, chiropractors, osteopaths), a performing arts doctor, and several medical professionals who are pipers themselves. I essentially analyzed how movement felt in my left pinky/ring finger every day for five years trying to find a hack or solution to play freely again.

I made a lot of progress from the dissecting and rebuilding of certain note sequences, but there was a lingering discomfort. I couldn’t tell if it was due to muscle memory vs. physical and eventually, and the emotional rollercoaster took its toll. It was almost a relief when I stepped back from playing four years ago (still secretly hoping that by not playing my arm issues would heal on their own).

Two years ago, after noticing increased numbness in my left two fingers I raised this again with my family doctor and this time went through a series of referrals and tests. I learned that the symptoms I was experiencing were caused by Cubital Tunnel Syndrome (entrapment of the ulnar nerve at the elbow), Tenosynovitis (a catching when bending/straightening) in my left pinky, and possibly Tendonitis (inflammation of tendons) during the 2013 summer.

After trying conservative methods of treatment (i.e., elbow pad, night splint), I opted for surgery to free the nerve in May of this year. The procedure was a success and I’m well on the road to recovery in terms of regaining mobility and strength in my arm/elbow. The nerve itself can take up to two years to heal, so time will tell how much my nerve speed and endurance can be improved.

Now that my nerve is freed and on the path to healing, I’ve tested out my practice chanter and pipes – it’s been fascinating to experience the impact of improving one variable of movement and it’s helping me to understand the remaining impact of others.

The straining/slowness (which I would describe as “quicksand”) that I used to experience when moving my two left fingers quickly has noticeably improved. However, five months after my nerve surgery I realized that the catching feeling in my left pinky must still be impacting the dexterity in my hand. When playing, I’m still experiencing awkwardness at the base of those two fingers and my guess is this is due to the pinky finger tendon catching when going from bent to straight. Tthis jolts my hand slightly and limits quick up and down movements involving the top hand.

When I had previously mentioned this symptom to health specialists, many didn’t know what it was. Two years ago, my neurologist labelled it as a Tenosynovitis (“trigger finger”), and she didn’t suggest any next steps, so I assumed it must not be a cause of my symptoms/playing limitation.

Taking my own advice described later in this article, I mentioned this remaining symptom to my Occupational Therapist specializing in hands, who I’ve been working with post-surgery to restore my arm/elbow. She quickly identified the cause, clearly explained it to me, and suggested next steps that I can take within the health system. I’m fortunate again that there are possible treatments for this ailment, so I’ve begun the referral process with my doctor to hopefully work towards a solution.

This new realization caught me off-guard emotionally. For the past two years, I believed I had full clarity on the root of my symptoms as ulnar nerve compression. While that was a main factor that required treatment, I’m also wondering if this pinky Tenosynovitis was contributing equally or more to the lessened dexterity in my left hand. Time will tell again whether this symptom can be improved alongside my nerve continuing to heal.

It just goes to show how ambiguous it tricky it can be to understand arm/hand injuries and their impact on playing. Let’s hope I’m nearing the end of these discoveries!

The physiology of movement

Before getting into the specific risks that led to my injury and many other musician ailments, I’d like to zoom out and look at factors that influence musical performance.

My arm surgeon not only helped me to better understand the factors that caused my injury, but also the variables that contribute to healthy, free-flowing movement in general.

Here’s my interpretation of her description:

- The body creates a stable base for our limbs to operate.

- Certain body positions and postures enable movement that requires less energy, i.e., typing on a keyboard with straight wrists is more energy efficient than repeating the same motion with bent wrists.

- Multiple factors can influence, improve, or impede the ease and flow of movement, i.e., posture, nerves, tendons, muscle, etc.

- The experience of free-flowing movement is the combination of these many variables, therefore:

- A deficit in an area can be a limiting factor on movement, i.e., even with the most efficient posture, a tendon/nerve/etc. injury may create a bound that limits the ability for effortless movement.

- Alternatively, perfection in all variables is not required to achieve free-flowing movement and improvement in one area may improve the overall efficiency and experience of movement, i.e., finding the right angle/positioning of an instrument, awareness of posture, building muscle strength and endurance, etc.

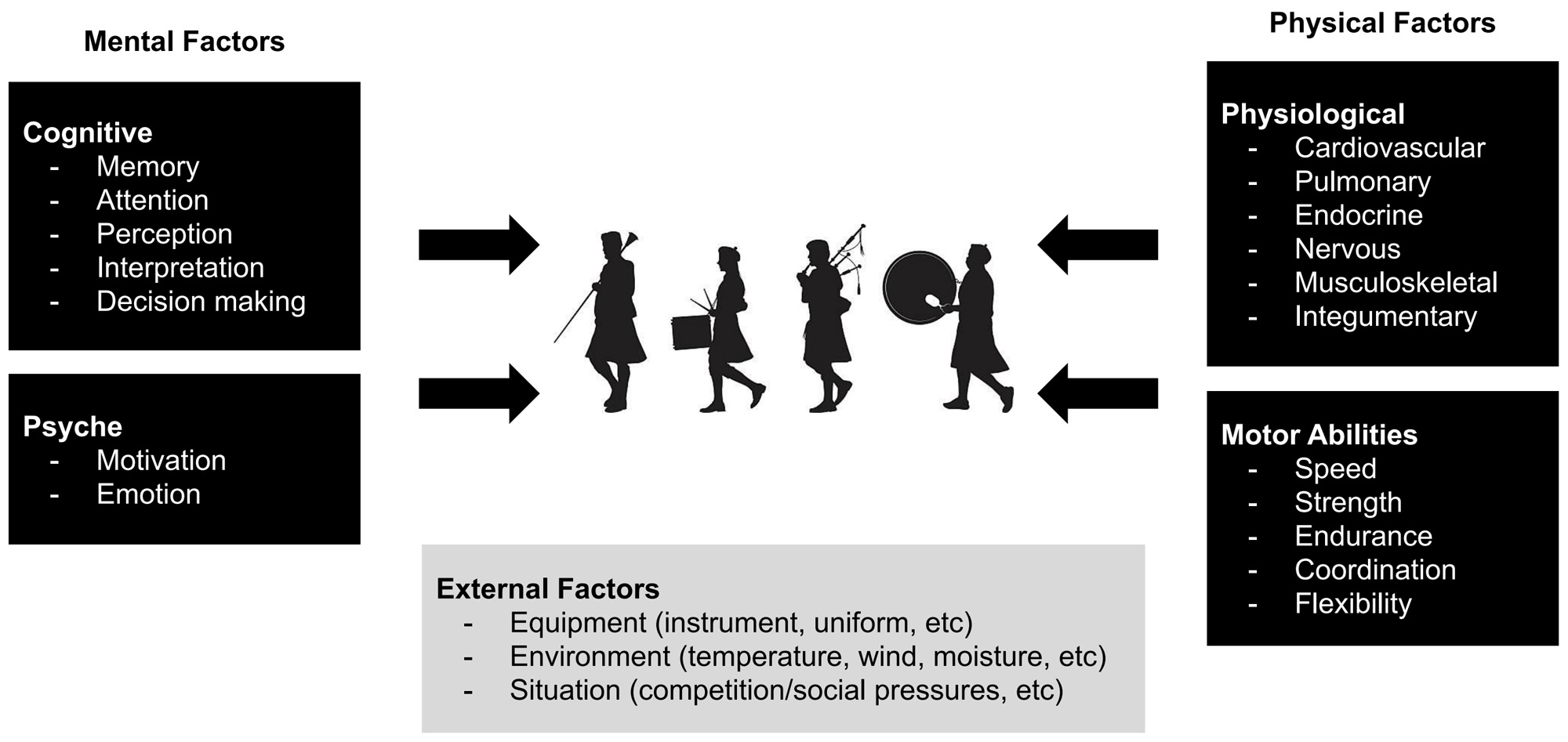

In piping and drumming, musical performance is affected by several factors, both internal (mental and physical) and external in nature (equipment, environment, situation). These factors are all interconnected and can hinder or improve a performance.

The below diagram illustrates a sample of factors that can affect and constrain a musical performance. Note: This may not be a complete list and each musician may experience unique influences.

Limiting factors of musician performance [1][2]

Anecdotally, here are examples of how these factors may affect bagpipe playing:

- Cold temperatures cause muscles to contract (any pipe band member who has performed in a Canadian winter parade will know this struggle!) whereas higher temperatures can slow down the speed of nerve signals. This hinders the speed and endurance of finger movements along with other potential mental or physiological impacts on the body caused by extreme temperatures.

- If the size or shape of a pipe bag isn’t suited to your body/arm length, this can lead to poor posture or uncomfortable playing positions. Your body may need to work harder to make the specialized movements to play a tune and more importantly, if not improved, may leave the player even more susceptible to repetitive strain injuries.

- I’ve tried many slight adjustments to my hand position and angles on the chanter, angle and height of the chanter stock, length of the blowpipe, distance of the drone stocks from the chanter, etc. (Don’t try these all at once!) Most often an instrument adjustment feels strange at first, but sometimes the mind adjusts, and it can improve the freedom of playing. By adjusting one variable at a time slightly, it allows you to gauge whether the change hinders or helps. As mentioned above, if something feels off while playing, keep searching for answers as playing through discomfort may lead to injury.

- On the mental side, I’ve heard talented pipers and teachers share the advice that while practicing, visualizing all aspects of an upcoming contest or performance can help lead to its success. On the day of a contest, players may have routines or rituals or that help to mentally prepare for the day. During an event, the ~3 minutes of tuning time in front of the judge(s) may be as much for settling down your own mind as it is for settling the pipes to the environment.

- There could be an entirely separate article focusing on the mental side of Highland music and there’s much more on this topic in general. The Inner Game of Music by Barry Green is a guide “designed to help musicians overcome obstacles, help improve concentration, and reduce nervousness, allowing them to reach new levels of performing excellence and musical artistry.”[3]

With so many internal and external variables interacting simultaneously to impact our experience while we play, it can feel daunting to navigate at times. The good news: we don’t need perfection in every variable to achieve the sense of free-flowing movement.

In my questioning to try to understand my ulnar neuropathy prognosis and inform my expectations for an outcome, my surgeon explained that my nerve function doesn’t need to be restored to 100% to achieve the feeling of free movement. There isn’t an exact number, but some amount of improvement to my nerve function, coupled with good posture, an ergonomic setup of the instrument, and balancing the other factors could all combine to bring a more comfortable sense of playing.

The pipes can be a temperamental instrument and, combined with the complexity of the human body, mind, and environmental factors, it’s to be expected that some days playing can feel effortless while other days nothing seems to be going right. It’s a normal part of the musician’s experience and being human. We should all strive to be self-compassionate and self-aware as we navigate learning and improving our playing.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of “The complexity and risks of playing the music we love” by Liz Sheridan.

Liz Sheridan is a Professional-grade solo piper who has also competed at the Grade 1 band level with the Peel Regional Police and 78th Highlanders (Halifax Citadel). In 2012, she finished a five-year double degree program (two simultaneous undergrads) in Business at Wilfrid Laurier University and Mathematics at the University of Waterloo, both in Waterloo, Ontario, and now works in HR Analytics/Technology with a healthcare marketing agency. She has been on a four-year break from competition, but recently completed her B-level band and solo adjudication exams with the PPBSO. She hopes to stay involved in the piping community and eventually return to playing when her remaining finger issue is resolved.

Thanks so much for your article. Although not nearly as severe as your situation, I to struggle with a physical issue while playing. Also, not anywhere close to the level of performance you have achieved. About 10 years ago I was diagnosed with arthritis in both my thumb joints. My constant focus is focusing on not having a death grip on the chanter. Not an easy task when playing a new tune or with movements that I struggle with. As I am able to relax my grip, I have noticed that not only has my technical playing improved, but I also don’t have the constant pain in my thumb joints that can last for several days.

Like athletes that get training on changing how they do things; for example a golfers swing, having them improve results and avoid repetitive injury; there should be a resource for us pipers to get help with the mechanics of playing to have a positive experience and outcome.

Look forward to what you have to share in Part 2.

Don Neil