The Art of Setbacks: Avens Ridgeway looks at how we can sustain ourselves and our playing through ‘repeated losses’

As a follow-up to our recent “Art of Losing” panel discussion on the possible psychological challenges that “repeated losses” can have on a competitor, we asked Avens Ridgeway, an Open/Professional-grade piper with a master’s degree in Organizational Psychiatry and Psychology from King’s College in London, if she might share her professional thoughts on the potential psychological impacts that could come from pipers and drummers’ incessant desire to compete.

(For clarification, Avens Ridgeway looks at “setbacks” that may differ in meaning for each competitor. If you are experiencing a mental health condition, consider speaking to a licensed mental health professional.)

The Art of Setbacks

By Avens Ridgeway

There are many apparent benefits to competition including motivation, a way to measure your improvement, and an avenue to perform. None of these advantages are a surprise. So why can’t we consistently approach competition after repeated setbacks from a rational standpoint? If we can understand what goes on within the mind, we can start to reframe how we approach competition, and more importantly, how we sustain ourselves and our playing through the inevitable setbacks.

In any contest, there is of course only one gold medalist. Where you fall within a prize list can have a certain impact on your mental state. Research has found that when people were asked to describe the feelings Olympians were experiencing in pictures and were unaware of how they placed, they typically described 1st and 3rd place finishers as happy. However, 2nd place finishers were described as having blank expressions. Researchers concluded 2nd place finishers often go over what could have gone better that would have resulted in a 1st place finish, instead of feeling good about their performance.

It can be valuable to look at brain activity during a competitive win to better understand what we experience during the alternative. When a competitor wins there is an increased release of brain chemicals which include dopamine and serotonin; both of which are associated with positive feelings. Dopamine is a reward chemical which enables us to feel pleasure. Serotonin is known as the feel-good chemical that when released, makes us feel happy. Consequently, there’s no surprise why chasing wins can be addicting, or at the very least, feel great. There is even a biological advantage of winning, referred to as “the winner effect.” This suggests when a human experiences a series of wins, they have an increased chance of winning in future situations that are more difficult due to increased confidence, focus, and learning retention.

The opposite holds true: during a competitive setback both dopamine and serotonin decrease. Thus, it is important for competitors to intentionally think about how they mentally approach competitions and also how they define what winning means to them personally.

When it comes to an individual’s well-being following repeated setbacks, it is likely one may feel an absence of pleasure, lower energy, decreased mood, negative thoughts, timidness, and fatigue. When these feelings are sustained over time, it can have a serious impact on the content of our thoughts. Negative thoughts, if left unchecked, can pose a significant threat to the competitor especially if they have a pre-existing mental health challenge. Our recurring thoughts become more ingrained, meaning the associated neural pathways have been used repeatedly, making them stronger. Our brains gravitate to established pathways, so these thought patterns can start becoming the default. We’ll refer to this point later when we talk about neuroplasticity. First, let’s look at what a competitor may already be coming to the boards with.

If a competitor experiences an underlying mental health challenge, they will likely be more susceptible to the negative psychological effects of repeated setbacks.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2022, globally one out of eight people experience a mental health disorder. While there are various types, anxiety and depressive disorders are among the most common. If a competitor experiences an underlying mental health challenge, they will likely be more susceptible to the negative psychological effects of repeated setbacks. Additionally, if a competitor is experiencing underlying mental disorder(s) at a level that is inhibitory and unmanaged, it can have negative effects on their performance and their ability to properly prepare for a competition. If you are struggling with mental health and find it hindering your ability to compete or even play, take the time to seriously address it, just as you would a physical challenge.

Consider anxiety, as it is one of the most common mental health disorders and has recently been on the rise due to various factors. When someone has an anxiety disorder, it’s a very different experience than someone casually saying they have anxiety about an upcoming contest. When stress is perceived, a section of the brain (the amygdala) alerts another part of the brain (the hypothalamus), which ultimately initiates our fight-or-flight response. When this response is activated, our adrenaline increases and we find ourselves experiencing physical symptoms (e.g., racing heart, faster and shorter breaths, sweating, etc.). If we fail to notice the stressor is no longer a threat, our body will continue functioning as though it is still facing the stressor. This means cortisol (stress hormone) will continue to be produced. Those living with anxiety disorders often experience physical symptoms (e.g., headaches, shortness of breath, nausea) and psychological symptoms (e.g., fearing the worst). These symptoms can inhibit a competitor’s ability to prepare, perform to their best ability, and/or find the joy during repeated setbacks. Telling a competitor with an anxiety disorder to “relax, stop stressing and just play” would be similar to telling someone to play their instrument despite having a huge leak in their bag.

Telling a competitor with an anxiety disorder to “relax, stop stressing and just play” would be similar to telling someone to play their instrument despite having a huge leak in their bag.

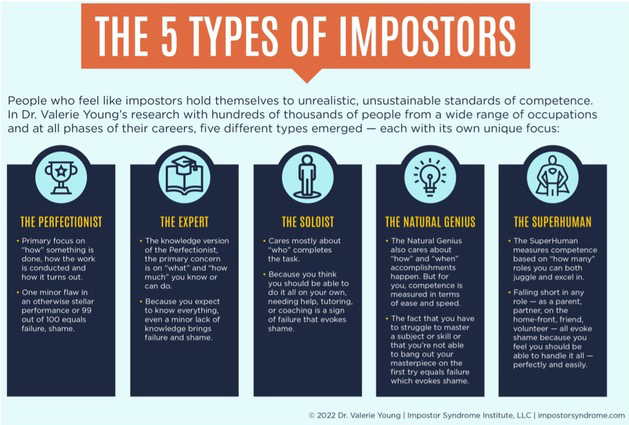

Commonly experienced with anxiety (and depression) is imposter syndrome which is a psychological experience and according to the American Psychological Association, is experienced by up to 82% of people. Broadly speaking, this phenomenon may manifest in different ways and can ultimately lead a competitor to feel as though they haven’t earned their accomplishments (e.g., “I’ve been upgraded to Grade 3 only because my instructor is on the grading committee.”) or aren’t as capable as others. It has been suggested that there may be five different types: perfectionist, expert, soloist, genius, and superhuman (see image for brief definitions). Some signs of imposter syndrome include: negative self-talk, self-doubt, overachieving, a failure to see one’s ability for what it truly is, and an authentic fear of being exposed as a fraud. It is not uncommon for highly successful individuals to experience this syndrome, in which case they credit their achievements to external factors instead of their own abilities. It can be helpful to think of this phenomenon on a spectrum. On one end, it’s easy to see how damaging this could be for one’s mental state. On the opposing end, it can be used as motivation to learn more and even adapt within a new setting.

Think about the headspace of a competitor who struggles with anxiety to begin with and is about to compete after a series of setbacks. Imposter syndrome may even be in the mix. Our thoughts have a significant impact on our reality. In neuroscience, the expectancy theory suggests the way in which a person expects a situation to go, initiates the same neurons to fire as if the situation was actually happening. This explains why we may notice physical symptoms of stress (e.g., heart racing, stomach hurting, palms are sweaty, knees weak) when we find ourselves imagining what could go wrong in a contest. Our brains can get stuck in patterns that inhibit us. If we’re in the habit of focusing only on the negatives, not only will we be more nervous but we will also miss any positives taking place. In terms of competing, while it’s of course constructive and healthy to identify areas to improve upon, it’s equally as important to broaden your attention to areas that have improved, or that are already going well.

Think about the headspace of a competitor who struggles with anxiety to begin with and is about to compete after a series of setbacks. Imposter syndrome may even be in the mix. Our thoughts have a significant impact on our reality. In neuroscience, the expectancy theory suggests the way in which a person expects a situation to go, initiates the same neurons to fire as if the situation was actually happening. This explains why we may notice physical symptoms of stress (e.g., heart racing, stomach hurting, palms are sweaty, knees weak) when we find ourselves imagining what could go wrong in a contest. Our brains can get stuck in patterns that inhibit us. If we’re in the habit of focusing only on the negatives, not only will we be more nervous but we will also miss any positives taking place. In terms of competing, while it’s of course constructive and healthy to identify areas to improve upon, it’s equally as important to broaden your attention to areas that have improved, or that are already going well.

[Are you enjoying and learning from this important article? Most of our nearly 8,000-article content is free, but we rely on subscribers, donations and sponsors to maintain pipes|drums. We appreciate and thank you for your support!]

This approach is supported by Shawn Achor’s research. In his book, The Happiness Advantage, he argues individuals achieve higher levels of success only after they are happier and more positive, as opposed to finding happiness following an achievement. Achor states, “It turns out that our brains are literally hardwired to perform at their best not when they are negative or even neutral, but when they are positive.” Having a positive mindset going into a contest also gives you more confidence. “Even the smallest shots of positivity can give someone a serious competitive edge,” Achor writes.

So, how can competitors achieve a positive mental state if they’ve experienced repeated setbacks, and especially if those losses are on top of an underlying mental health condition? The remainder of this article takes a look at several suggestions. Keep in mind this is by no means an exhaustive list and a competitor should find ways that work well for them.

First suggestion: Adopt a growth mindset to competing

First suggestion: Adopt a growth mindset to competing

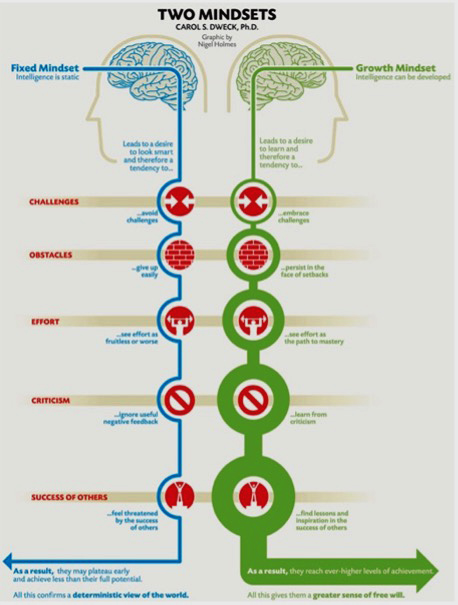

Psychologist Dr. Carol Dweck is known for her research which focuses on the difference between a growth mindset and a fixed mindset. Those with a fixed mindset feel they have to prove themselves repeatedly (e.g., “I need to win on Saturday to prove to everyone I belong in this grade”). Conversely, growth mindset individuals understand they can improve through effort, strategies, and help from others. They see the value in adversity and understand how effort can reshape their situation, unlike those with a fixed mindset. When facing setbacks, Dweck found individuals with a growth mindset were less likely to quit. These individuals were eager to address challenges and continue working to move forward. When a competitor finds him/herself in a season of setbacks, it would be worthwhile for them to check their mindset. Hopefully, it will be focused on how they can apply personal effort and learn from their teacher or peers in order to continue growing and making progress with their playing.

If you create a practice routine that you look forward to showing up for daily and enjoy doing, your happiness will increase. And as previously discussed, happiness is the precursor for success.

Second suggestion: Fall in love with the process, not the outcomes

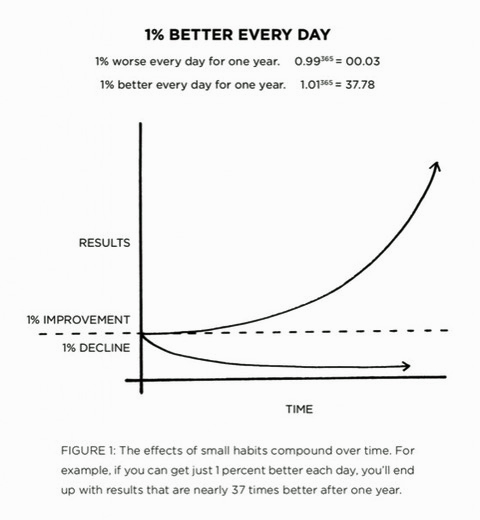

James Clear discusses the 1% rule in his book, Atomic Habits. An atomic habit, he defines, “is a regular practice or routine that is not only small and easy to do, but also the source of incredible power; a component of the system of compound growth.” Showing up daily and making tiny gains have a significant impact on overall results after a year. Clear also argues that goals, once set, really don’t matter other than providing you with a sense of direction of where you’re aiming to go. Instead, desired results are much more an outcome of the systems you follow (so think practice routine, night before/day of contest routines, tune-up, etc.). Committing to, for example, a practice system that you put in place and enjoy, instead of focusing on needing to win a certain event, is more sustainable over the long-term and will result in improvement. If you create a practice routine that you look forward to showing up for daily and enjoy doing, your happiness will increase. And as previously discussed, happiness is the precursor for success.

James Clear discusses the 1% rule in his book, Atomic Habits. An atomic habit, he defines, “is a regular practice or routine that is not only small and easy to do, but also the source of incredible power; a component of the system of compound growth.” Showing up daily and making tiny gains have a significant impact on overall results after a year. Clear also argues that goals, once set, really don’t matter other than providing you with a sense of direction of where you’re aiming to go. Instead, desired results are much more an outcome of the systems you follow (so think practice routine, night before/day of contest routines, tune-up, etc.). Committing to, for example, a practice system that you put in place and enjoy, instead of focusing on needing to win a certain event, is more sustainable over the long-term and will result in improvement. If you create a practice routine that you look forward to showing up for daily and enjoy doing, your happiness will increase. And as previously discussed, happiness is the precursor for success.

Third suggestion: Find your shot of positivity

Remember Achor’s research from above: “. . . our brains are literally hardwired to perform at their best not when they are negative or even neutral, but when they are positive.” Find sources of positivity that can be drawn upon before a contest (unless of course it’s having a beer then maybe wait until after your events). If you can draw upon a positive memory, pull up a short video clip, or remember you are fortunate to have an opportunity to share your music with others, that can help put you in the right headspace.

Fourth suggestion: Identify your controllables

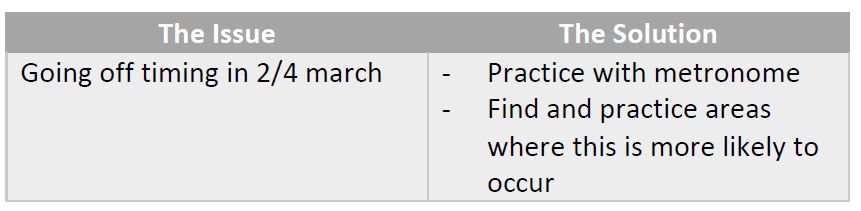

You can refer to what psychologists call the Zorro Circle: when you feel overwhelmed by what you are trying to achieve, shift your focus and concentrate on smaller, more controllable goals. The key word here is “controllable.” If your goal is to win on Saturday, that is out of your control and therefore should be out of your mind. If instead you focus on improving your timing, for example, that is completely within your control. Setting a controllable goal ahead of time, can help focus your preparation on a specific area; in this case, spending time with your metronome.

If you’re able to improve your timing at the next contest, it shouldn’t matter where you place since you achieved what you set out to do. This relates to Bruce Gandy’s “One-eighty Factor” chart that he introduced in his book Performance: Delivering Your Own Awesome. If an identified issue is truly within your control, you will be able to create steps to address it within the chart’s solution column. So, if you’re inconsistent with timing, learn to practice with a metronome. However, if you’re focusing on whether the judge is going to like your performance better than the other competitors this weekend, there is nothing you can do to prepare for that in the solutions column (except of course focusing on preparing and delivering your best performance). Anticipating how others will play or what may be most important to the judge that day are all out of your circle of control. Using Bruce’s One-eighty Factor chart is a great way to identify if something is actually within your control or not, as well as provide focus and structure to your practices.

Change the focus from “needing to win in order to have success” to an intrinsic focus that is meaningful to you will have a more sustaining effect on motivation to play and compete even during setbacks.

Fifth suggestion: What is your purpose?

What is your why is for competing? In the earlier Art of Losing videos, there was a discussion on how solo competitors have to win certain competitions in order gain entry into more prestigious contests. This concept can be applied to competitors coming up through the grades. In order to gain points and be upgraded, you need to win. If a player starts competing at a young age, this narrative and focus can become a heavily ingrained neural pathway. Change the focus from “needing to win in order to have success” to an intrinsic focus that is meaningful to you will have a more sustaining effect on motivation to play and compete even during setbacks.

Ultimately, it all comes down to finding ways that help you stay focused on the bigger picture of why you compete and refer back to it regularly, especially during times of setbacks. This could be focusing on getting the chance to share music for one competitor or the chance to track personal progress for another. Quite likely, what you find to be helpful to focus on will be different than what your friends, peers, or even instructor, may focus on. Although we all love and want to win, don’t let repeated setbacks be a reason you stop competing.

If you are experiencing a mental health condition, consider speaking to a licensed mental health professional. If you are experiencing thoughts of suicide, in the United States, please call the National Suicide Hotline at 988 immediately.

Avens Ridgeway is a professional solo competitor who recently reentered the professional/open solo competition circuit with great success at the P-M Ian Swinton Open. She has a BA in Psychology from Lyon College and an MSc in Organizational Psychiatry and Psychology from King’s College London, and works at a consulting agency where she coaches individuals within education, business, and athletics in helping them maximize their performance. Additionally, she is an independent business analyst for a higher education consulting firm. Originally from Maine, Avens Ridgeway lives in St. Joseph, Missouri.

NO COMMENTS YET