Ken Eller: the pipes|drums Interview from the Archives

When Ken Eller left us on July 26, 2024, an unfillable void was left in the piping and drumming world. The outpouring of grief and remembrances for “The Captain” was universal and consistent. His infectious positivity and charisma seemed to touch virtually every person involved in the competitive art, regardless of age or location.

In March 2004, we met with Eller for an exclusive pipes|drums Interview. He was 57 and six months removed from what would turn out to be his final season as a competing piper. According to him, things did not end well. He was raw with emotion, feeling pushed out after a competitive legacy of nearly 50 years at the Grade 1 level, many of those as pipe-major of Clan MacFarlane. This band blazed the way for non-UK bands travelling to Scotland to compete regularly at the World Championships.

In the interview, Ken Eller is frank, honest, and prescient. Not yet on the judging panel of the Royal Scottish Pipe Band Association, Eller foresaw the negative ramifications of ever-expanding rosters at the top level, ever-sharpening pitch, and the loss of community with bands worldwide.

We’re pleased to bring readers this exclusive, copyrighted discussion with the late, great Ken Eller, including our original introduction. (Please remember the sidebar lists are from 2004.)

If there were such a thing, Ken Eller could be the president of the Association of Positive Thinkers. The piping and drumming world would be challenged to find anyone more enthusiastic, motivated, and positive than Eller, who has been an ultra-popular personality since the 1960s, first in Ontario, then in Scotland, and now worldwide.

If there were such a thing, Ken Eller could be the president of the Association of Positive Thinkers. The piping and drumming world would be challenged to find anyone more enthusiastic, motivated, and positive than Eller, who has been an ultra-popular personality since the 1960s, first in Ontario, then in Scotland, and now worldwide.

As pipe-major of Canada’s first “super band,” Clan MacFarlane, for nearly 20 years, Eller was given the nickname “Captain,” which more people refer to him as than “Ken.” Indeed, Eller captained a tight ship at “The Clan,” navigating the band to eight North American Championships (1972, ’73, ’74, ’75, ’77, ’78, ’80 and ’82.), numerous PPBSO Champion Supreme Awards, and several successful trips to compete in Scotland at a time when such a thing by any non-UK band was an anomaly.

Known for its rich, robust and powerful sound, The Clan, by emulating the Glasgow/Strathclyde Police and Shotts & Dykehead – the winningest Scottish bands of the time – raised the stakes on the Ontario scene. Eller’s leadership and his self-admitted attempt to clone everything that Shotts pipe-major Tom McAllister did elevated the Ontario standard and prompted bands like Ed Neigh’s Guelph and Gord Tuck’s McNish Distillery to rise to a higher level. Perhaps most importantly, The Clan inspired future bands like the 78th Fraser Highlanders, City of Victoria, and Simon Fraser University to seriously compete for, and win, World Championships.

Because the Captain and the Clan aspired to international greatness first, the pipe band world owes him and them a debt of gratitude for making the Grade 1 band scene the international spectacle it is today.

Born February 18, 1947, in St. Catharines, Ontario, the pipes were basically foisted on Ken Eller. Through his initial instruction with Dick MacPherson, he played with the local band. The great John Wilson subsequently honed his skills, and Eller was quickly recruited to a relatively new band, the Clan MacFarlane. After a few years with The Clan, Eller was again recruited – this time to take over from Jim Greig as pipe-major. With that, his focus became singular, and solo competition gave way to the band.

The 1970s were the Clan’s heydays. The club-like atmosphere of the band, on the one hand, gave it solidarity, familiarity, and consistency, but on the other hand, stifled its growth and ability to change with the times. By the time Bill Livingstone’s 78th Fraser Highlanders emerged in 1982, The Clan was still playing extremely well and routinely beating the 78th in competition, but its personnel were growing ever longer in the tooth. As musical trends leaned to the innovative, the fast, and the technical, The Clan was challenged to adapt.

By 1987, Eller had given way to a new pipe-major, Joe Rennix, and the Captain decided shortly thereafter to retire. He dedicated the next four years to working in partnership with the bagpipe maker Jack Dunbar. He also became a fitness and diet fanatic, shedding forty pounds, training as a triathlete, and entering competitive triathlons – a sport that his wife, Diane, still enjoys and competes in on an international level.

In 1993 he returned to the band scene to play as a back-rank piper with his former foes, the 78th Fraser Highlanders. He says his 10 years with the 78th were his favourite, and the task of learning and playing two hours of concert material was an irresistible and ongoing challenge that Eller met, as usual, with optimistic enthusiasm. He added seven more North American Championships with that band, bringing his total to 15 – a sure record. Eller left the 78th Frasers in 2003, and has since dedicated his time to teaching private lessons, conducting workshops worldwide throughout the year, and accepting various judging invitations. He does not rule out again returning to the band scene.

After 32 years as a professor of mathematics at Niagara College in St. Catharines, Eller retired early several years ago and lives comfortably on his 40-acre property in the quiet town of Fonthill, Ontario. He has two children, Cam, 22, and Lindsay, 26.

Since we last talked with him in 1988 in a brief and not well-distributed interview, it made sense to return to The Captain for this exclusive interview with The Captain, Ken Eller, one of the piping world’s most well-liked, charismatic, popular, and accomplished personalities.

pipes|drums: When did you start piping, who taught you, and who do you credit for your success?

Ken Eller: It goes back to the mid-1950s. My grandfather was a New York City Irishman by the name of Roderic O’Neill. Nearing the end of his life, he wished for a piper in the family. My mother selected the eldest son, and I ended up starting pipes in 1955, the year my grandfather passed away.

I went for lessons in St. Catharines, Ontario. Hugh MacPherson from Edinburgh had his start in the St. Catharines area, and he actually reversed the immigration by going back to Edinburgh to launch the parent company, Hugh MacPherson Ltd., on West Maitland Street in Edinburgh. His brother, Dick, ran the St. Catharines store, and he offered lessons to anybody who wanted them.

p|d: Do you credit Dick MacPherson with your success? Did he inspire you?

KE: I would say Dick was a father figure musically for me. It was my mother who gave me my drive. When I learned the scale, my mother would sit at the kitchen table and beat rhythm with a twelve-inch ruler to make sure that I went from one note to the other. She didn’t know anything about pipes, but she knew doh, re, mi.

Dick was a gifted teacher. He was unselfish. When I got to a level that Dick was perhaps uncomfortable with, or he had decided that I had to start learning piobaireachd, he contacted John Wilson in 1961. That was really important, because he didn’t try to hold me back.

p|d: You would travel to Toronto for lessons from Wilson?

KE: Yes, and in those days that was quite a trek for a fourteen-year-old boy. I would get on the bus in St. Catharines at 7:30 a.m., be dropped off at Strachan Avenue to go down to Fort York Armoury for John’s classes, and that would be sometime around 10:00 to 12:00 in the morning on a Saturday. Then I’d sit around in Toronto until 5:00 at night to get the return bus to get me back to St. Catharines at 7:30. That was every Saturday, and we did that for several years.

p|d: What about John Wilson? What kind of a character was he?

KE: Dynamic. I was in awe of him. Anything that Mr. Wilson taught or showed us, I just went home and practiced fiendishly. I couldn’t get enough from him. It wasn’t just piobaireachd. He insisted on highly structured 2/4 marches, strathspeys, reels, and jigs.

He enjoyed teaching us. Every week he had some piping anecdote, so I got history for the first time, which I had never received prior. Just leaving that seed for learning and becoming a student as young as fifteen or sixteen was really important. My only regret is that I didn’t continue the solo end because of band commitments later on.

p|d: What about bands? Did you play with one from the very beginning?

KE: Dick MacPherson was my instructor. I played with the St. Catharines Pipe Band, where he was pipe-major. John Kirkwood Sr. the lead drummer of the St. Catharines Pipe Band left and formed the Clan MacFarlane in 1957. Around ’59 or ’60, they invited Jim Greig to return to Canada from Edinburgh where he was playing with the Edinburgh City Police.

I was still with Dick MacPherson, and in 1961 and ’62 there was the usual push from the Clan MacFarlane people to join, but I remained with Dick. I owed Dick my loyalties, and my parents did think I was little bit too young to be going with the high-moving Clan MacFarlane.

But I did join Clan MacFarlane in 1963. This was a year prior to Dick’s death. I can remember I talked to Dick about it, and it was heart wrenching for him in a way, but I promised him that I would maintain my commitment with the St. Catharines Pipe Band as well. That seemed to appease him, and it certainly pleased my parents.

p|d: How did you maintain that commitment?

KE: It was a parade band, so it wasn’t much for me to do the parades and what have you with the St. Catharines Pipe Band, and then start working on the Clan MacFarlane material. Clan MacFarlane was playing in “B Grade” back then. We had two grades, a Grade A and a Grade B, which would be the equivalent of our grades 1 and 2 now. That was the entry-level at that time, so you can well imagine there weren’t a great number of bands at the games in the 1960s.

The A Grade was primarily the big bands of the time. The Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders of Canada were going very well in Hamilton. Of course, the 48th Highlanders were really on top of the grade in Toronto. There were a few other civilian bands, like the Caber Feidh and St. Thomas, so the Clan MacFarlane had to prove its worth. It took them another two years to get to Grade A.

p|d: What was the Ontario piping scene like in the 1960s?

KE: In the 1950s and ’60s, there were basically three recognized master pipers in this part of the world, and they were George Duncan in Detroit – he had Lewis connections, John Wilson in Toronto with his Edinburgh connections, and Alex MacNeill in Montreal, son of Blind Archie. So you can imagine the piping scene was really regionalized, and if you were going to advance in piping, you basically would go to one of these three people.

That meant that Detroit had a strong piping scene. London was surprisingly strong. The 3M Corporation had a band there. And Hamilton was good with the Argylls, and of course Toronto with Wilson’s teaching, and then Montreal. When I call these people masters, we respected them as such. That’s different than it is today. Maybe we have yet to produce our recognized masters today in Ontario, although we’ve got all the prizewinners. There’s a big difference between winning a Gold Medal and being a recognized master. Perhaps it was their immigration to Canada that set these people apart. They were giving us the true story and that was coming from Scotland.

There were only a handful of teachers. You had your local teachers, but if you wanted polishing, you had to go to one of the recognized masters. Most of them had highly successful students. The people who were successful in the professional ranks at the time – Archie Cairns, Billy Gilmour, Reay Mackay, Gord Tuck, Chris Anderson – these are famous names in Ontario piping.

If you were going to compete in the Open events, there was a very strong list on any one day. But the music requirements were far different than what we have now. Our schooling was heavily grounded in marches, strathspeys, and reels. Even jigs and hornpipes weren’t the norm yet in bands. And you only had to submit one piobaireachd. You could pick one tune and play it your whole competitive career.

If somebody would say “Chris Anderson,” I’d say “The Bells of Perth.” You were known by your tunes. Now with all the medal tunes a player is far more diversified. I spent a whole year playing “The Pap of Glencoe.” Great tune. Knew it inside out, but I didn’t know anything else.

The peer groups that we had were basically age groups because we competed in age groups, so there was no such thing as a senior amateur player or what have you. It was like Scotland still is today. We were kids together. We went up in the 16 and Under, and we all competed. We formed our competitive groups there.

Then we graduated to 18 and Under and then were thrown into the Open. Some of us floundered, and some of us kept on going. My close friends at the time around piping were developed through these age groups.

p|d: What about Ontario? How did it consider itself? Did you know what was happening in British Columbia? Did you think that Ontario’s playing standard could match Scotland’s?

KE: In the early 1960s for us there was no other place in the world to play pipes except Ontario. We didn’t see Scotland as an alternative, nor did we see or did we know much about anything that was going on in western Canada. Travel was far different then. The thought of travelling to Scotland for a piping competition was almost unheard of in 1960. We’re talking prop planes. It would take fourteen hours.

We rarely travelled out of Ontario. Occasionally, somebody might get down to Nova Scotia, for example, or Prince Edward Island for a summer event, but we never really knew that there was a world outside Ontario.

Communications were similar. We bought vinyl discs, like Muirhead & Sons winning the World’s in 1957 in Belfast, for example. Princes Street Parade, Pipe-Major Robert Reid’s band, and so on. But that was a world apart from us.

But that started to break down as travel became a little easier. In the Clan MacFarlane, we had our first glimpse of it in 1965 when we decided that we would go to Scotland in 1966. The Caber Feidh in Toronto had the same inclination, and so did the Worcester Kiltie Pipe Band in the eastern United States.

Our eyes were opened to the bigger world of pipe bands – and everything else – in Scotland. This was prior to our current players going over to compete in the solos. Billy Gilmour might have been one of the few. Archie Cairns had been over, but very few at that time.

Western Canada still wasn’t opened up to us. It wasn’t until we got going in the early 1970s, with the Canadian National Exhibition contests, and the events that Archie Cairns promoted in Ottawa around 1974. Western bands were flown in and travelled to eastern Canada for the first time.

Port Moody – the predecessors of Simon Fraser University – City of Victoria, and Triumph Street came to compete at the Intercontinental Championship at the CNE. Jamie Troy, the pipe-major of the great City of Victoria band, said that they were awe-struck by the sound that we were producing in Ontario. But they went to school on that, and the very next year, Jamie brought that City of Victoria band back and won the Ottawa contest going away.

All of a sudden, we were really aware that there was a major piping scene on the west coast of Canada.

p|d: Back to Clan MacFarlane’s 1965 trip to Scotland. Did you compete?

KE: Yes, and I was looking at the master sheets recently. The World’s was in Inverness and Muirheads won it. That was in the middle of their five straight titles. Second in piping, though, was the Caber Feidh from Toronto. That was an amazing result. The judges were under cover and couldn’t see which band was playing, so naturally the excuse went up, “They fooled the judges.” Not so. They played well and earned the prize. Worcester and the Clan MacFarlane were in the middle of the pack. We were about ninth or tenth out of about 17 or 18 bands.

p|d: That must have been a shot in the arm for the Ontario scene.

KE: Oh, yeah. The judges received us pretty favourably. We weren’t world-beaters, except for the Caber Feidh, which placed fifth overall in that initial trip. So, they were the trendsetters. They broke ground for us all.

p|d: What was the reaction from the Scottish players? Was there a buzz about these bands coming over?

KE: If there was a buzz, I didn’t hear it. We went over, did our thing, flew back, and put plans in motion for the next trip. As we continued to go to Scotland, we made relationships with the various bands, so we got to know the players and we were accepted as competitors. Win or lose, the attitude was that it was just another contest.

p|d: Did the Ontario bands take competition more seriously than the Scottish ones?

KE: I didn’t find that. I did find that we often didn’t do as well as we had hoped. In every case, it wasn’t because of some bias in the judging; it was more basic technical errors that we made, like blowing an attack or somebody going off the tune. However, we were making an impact. By 1974 there were a number of household names in Scottish solo and band piping coming to Canada for schools: Seumas MacNeill had started his Brockville schools. John MacFadyen was coming to Ontario. Donald MacLeod was going out west. Bob Hardie was going to Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.

Positive feedback was going back to Scotland about the playing here. We took a very good Clan MacFarlane band over in 1974. It was huge for the times. We had all of 16 pipers and a drum corps of six. We had easily won Maxville that year. A Glasgow Herald reporter was waiting for us at the airport and took me aside to do an exclusive interview right there on the spot so that they could roll out the press with a big Canadian band coming across. We got the biggest spread the band ever had. I’m sure that this made our Scottish competitors sit up.

It went even farther than that. BBC Wireless, I believe at that time, took me up for an interview for Seumas MacNeill’s “Chanter” program. He had touted how good the Clan MacFarlane was going to be. Well, that was when we became chumps rather than champs. It was a real set-up on us.

p|d: How did the band do?

KE: We blew the attack, and we were out of the list. We were maybe eighth or ninth. Shotts & Dykehead won it that year with a fabulous sound. New Sinclair chanters with big reeds. Yeah, we were chumps.

p|d: What about the Clan’s overall success? What was the success formula?

KE: Corny as it might sound, just hard work. What we might have lacked in individual talent, we made up for in determination. Jim Greig, the first pipe-major of the band, led by example.

I continued during my tenure. Practice every Sunday. If we were competing during the summer, we came back from the games on Saturday night and we practiced Sunday, every single Sunday. We took the pipes out of the box on Sunday, and we refined the sound from the previous day, and we went through technical stuff that we could have improved while it was still fresh in everyone’s mind.

p|d: Whether you won or lost?

KE: It didn’t make a single bit of difference. That was the routine. Then we practiced Thursday nights, so we never had a letdown. Living down in Niagara has its advantages and disadvantages. If you’re there as a group, you stay together as a group. Also, people won’t travel around the Golden Horseshoe to get to you, so you’re not able to attract players. We ended up with a group of ten or twelve guys who basically, from when they left school, grew up together, and they stayed together right through my whole tenure. Our drum section was very stable, starting with Jim Kirkwood, his student, Bob Downes; then John Kirkwood Jr., who eventually went to Muirhead’s. Downsey was always there to fill the gap when we needed him between stays of the others The percussion all came from the same roots (John Kirkwood) during those years.

“The old boys become older boys, and the thing starts to change.”

p|d: So, stability was a feature of the band’s success, but the whole thing fell apart a few years after that. Was it really that solidarity, the old boy’s school, which was responsible in some ways for the Clan’s demise?

KE: Spot on. We were not doing the teaching, and I find this terribly ironic right now. I profess to be a teacher. My whole career was teaching. My love is teaching the pipes right now, yet I wasn’t teaching significantly during my tenure as pipe-major. We didn’t have the young fingers coming in. We didn’t have the young players. An occasional player would enter the group, but we weren’t bolstering the strengths of the band. Equally important is that we weren’t adding new musical dimensions to the band. With no new personnel, we didn’t get new ideas. You go back to the well so often, it becomes dry.

The old boys become older boys, and the thing starts to change.

The first time that dawned on me was listening to the 78th Frasers in 1987 when they played “Journey to Skye.” I said to myself, “Where did they get this? How could the Clan ever get anything that’s going to musically compete with what they’re doing?” There was a whole new generation of thought. We were very much trapped in our traditional ways.

p|d: Was it kind of a club mentality?

KE: People might have had that impression of us. We were just happy to be together. If we stopped to think about it, we’d say, “Why don’t pipers come here?” But we never went out and solicited pipers. I never made a phone call in my life to ask a piper to come down. Big mistake! In fact, I turned pipers away.

When a trio from the Erskine Pipe Band approached me to join, I said, “No, stay where you are. If you leave that band, you’re going to bust them up.” The Erskine band was a good Grade 2 band, and so I sent them back. It was unheard of to turn pipers away, but that’s how we thought. It wasn’t “win at all costs,” and I’m often reminded of that decision in later times.

p|d: How did Clan MacFarlane react when the 78th Frasers came out with Live In Ireland? Did you try to do some things to inject some new life into the band?

p|d: How did Clan MacFarlane react when the 78th Frasers came out with Live In Ireland? Did you try to do some things to inject some new life into the band?

KE: It was certainly a jolt. We tried to do some fun things. We had to suddenly look at the musicality of what we were doing. With the understanding that, ” the Frasers are certainly far more creative than we are,” we did our little bit to contribute, but still keeping within the realm of traditional music.

p|d: Clan MacFarlane always had a bigger, more powerful sound. Was there ever an attitude that, “We’ve got the sound, they’ve got the pizzazz,” we’ll be okay.

KE: Medleys were in full swing then, and I think we were resolved fairly early on, after seeing what the Frasers had put together, that first of all they had as many good players as they could possibly reach out to at that time around the Toronto area. With our sound and our technical ability, march, strathspey and reel contests might very well go to us. We worked hard to change our medleys, but we couldn’t cross the musical threshold, as the Frasers did. We certainly had to settle for the fact that we knew that our music appealed to a different audience.

p|d: But at the same time the Strathclyde Police was incredibly successful with sound.

KE: Yes, Strathclyde was one of the best bands of all time. If you look at Clan MacFarlane’s repertoire during that time period, you’d see similar stylistic aspects to our medleys; for example, opening with 2/4s, a block of reels, perhaps putting a set of jigs together, but only playing two parts of each one so we get a little more variety, and using a traditional air, and little two-part hornpipes. Iain MacLellan was a pro at it, and we took a real shine to that. Rather than the Clan leading the way musically, we were emulating what was winning. But if anyone ever compared us with the Strathclyde Police, I’d be honoured.

p|d: What differentiated Clan MacFarlane from other top bands?

KE: In the 1970s we had Muirhead & Sons, but they were tailing off. Then, Dysart & Dundonald came through the ranks. Strathclyde and Edinburgh City Police were still there. If anything, we patterned the band structurally after Shotts & Dykehead. Our drum corps in the old Clan had come from the Shotts, so there was always an affinity. Tom McAllister was making our reeds, and assisted with chanters. He also helped in my education as a pipe-major. He was a great friend. I tried to emulate him in every way. We tried to clone Shotts.

There are very few bands that have been mavericks at this game and been successful. Invergordon tried and didn’t succeed. The 78th Frasers were probably one of the few. The Strathclyde Police didn’t win all those championships by being mavericks with the music. They stuck to tradition and played with technical excellence.

p|d: You’ve seen the 1960s, ‘70s, ’80s, ’90s, and now we’re into the ’00s. Which is your favourite decade in your career and why?

KE: No question, the 1990s. The 10 years I spent with the Frasers, because they were 10 years of musical enlightenment. It opened my eyes up to an awful lot of raw and cultivated talent. I can start right from my first year in the band with Michael Grey, Jim McGillivray, Bruce Gandy, yourself – these are players who were above the standard that I was used to with the Clan. We had a different set of skills with the Clan, and I was being introduced to some of this music and seeing where it actually came from. It was a great learning experience.

It was just a great time. I can think of some of the performances that we had and some of the music that we put together – tremendous!

p|d: Was some of that enjoyment because you were able to relax a little bit, not being in charge?

KE: Yes, I had no other responsibility except to play well. I came in as a back ranker. I knew my position in the band. It was exactly what I had cultivated within the Clan. You’ve got one leader and one musical director, and when your opinion was sought, you gave it. But I gave little input to the musical direction of the 78th. I learned the music and contributed where I could in some of the non-musical functions of the band.

p|d: The 78th Frasers might have been musically forward, but tonally perhaps a bit behind. Did you ever think when you went into the band that you would be tapped for your expertise in sound?

KE: Yes, no doubt. But I learned my position in the band very early on. I once said to Bill, “You know, you tape your D’s too much. They’re flat, Bill.” He says, “You’re right, Captain. But they’re my D’s and that’s what we’re going to play.” I loved it! I instantly knew my spot. We were friends talking, and I understood exactly. It was a different sound. I was used to a chanter that was sharper on the low A, a little flatter on the B. In other words, an unaltered Sinclair from the 1970s, with no carving of the chanter. I didn’t tape the low A for perfect intervals. I looked at sound from a unison perspective, and made sure that the chanters were as close together as they could be.

But I did think that I had something to add. With my experience with Jack Dunbar and working with the chanters, that desire to contribute was realized when we carved chanters for the very first time. We took our Sinclairs and went to Bill’s house where Bruce Gandy and Bill played the chanters all day and I did the carving. It was an attempt to raise the pitch of the Sinclairs that we had at the time. After that I was very satisfied that I had at least contributed something, tonally, to the band.

p|d: You joined the 78th Frasers in 1993. What was it like going to a band with totally different music direction?

KE: I had been fortunate to have four years out of the pipe band scene. I had been cleansed of anything prior to 1990, so it was almost like starting a new career. But you bring a certain set of skills with you to the new organization, and my initial skills – maybe my final set of skills at the end as well – weren’t compatible necessarily with their music. My styles of playing marches, strathspeys and reels, and perhaps the jigs, the way they pulsed the jigs and the roundness to some of the reels – these were new and exciting times for me, because I had to listen. I had to learn.

When you’re directing your own band, you learn less, because you hand out scores you have written, that you know, to be played in your style. For the first time I was finding out what it was like to be led and play somebody else’s music. It was a learning period.

p|d: How difficult was it to join at age 45?

p|d: How difficult was it to join at age 45?

KE: I had kept in really good physical shape since leaving the Clan, and I had little problem with the physical adaptation. It was more a mental challenge. I had to re-engineer my learning techniques, and I had to find out, maybe for the first time in my life, efficient ways of learning music. That, combined with learning how the music’s put together heightened the anxiety. I came in January and they had a concert in April, and it was expected that I would have 60 new tunes in my head. I’d never done that. My methodology in learning had to be radically changed.

p|d: What about Grade 1 bands today? Are time commitment demands making bands feasible only for those under 30?

KE: The whole competitive scene is a young man’s game. Look at the front rank of Shotts or Field Marshal. You just don’t see many grey-haired guys. The leaders of the top bands, though, are people of age, of musical maturity.

p|d: Should more bands give pipe-majorships to younger players? Is it a myth that you have to have a lot of experience to run a good band?

KE: I don’t think it’s a myth at all. You have to establish your credentials. You do that by being thrust into the middle of the competitive arena. The current pipe-majors of top bands have established, once they were given the opportunity, that they were musically inclined for the job, they had the set of tonal skills for the band, or they had a good supporting cast that could bring that out for them.

But just to purposely pick somebody, or thrust people of young age into that situation, it’s still the best man for the job. I got thrust in at a young age. I took over the Clan in 1972 at twenty-five. That was young. I would be the first to admit I lacked musical maturity, and if I ever told you how bad the first two contests sounded! But the learning curve was very steep, so you soon adjusted. It was a question of circumstance. If people present themselves now with a good set of skills, then there’s no reason why a younger person can’t take over a band.

p|d: Almost all bands today have something like a pipe-major-by-committee approach. When you were pipe-major of Clan MacFarlane, did you run it single-handedly, or did you delegate responsibilities?

KE: It was much the same way. You couldn’t put music on the table that the band didn’t really enjoy playing, so you searched for that music, and when it came time to put medleys together and sets, the powers to be with the band, certainly the pipe-major and the pipe sergeant, were fundamental in selecting that music, and then it was presented to the band.

As a result, we might have been even a little too democratic. The number of times that I put music out only to have it end up in the wastebasket! As the band progressed, we needed more input from the drum section, and we encouraged that, but perhaps not enough. In the mid-1970s we had guys like Scott MacAulay who was were always bubbling over with good ideas.

p|d: Is it even possible today for a top pipe band to be run by one all-powerful pipe-major?

KE: Every top band has one person at the top. Shotts has Rab Mathieson; Field Marshal, Richard Parkes; SFU, Terry Lee. Each one of those people are extremely strong. They usually have a great leading-drummer there as well. A tandem of two strong people take the band to the top. Every one of those bands has that in common.

p|d: Who is the better pipe-major? You or Bill Livingstone?

KE: I can’t bite on that one! When you get into the echelon of Grade 1, you’ve done many things right. The comparisons of styles between Bill and myself, or any other pipe-major, could focus on the differences. The skillsets necessary may be similar. A comparison between pipe-majors is possible, but a ranking? No way!

p|d: Iain MacLellan talked about “man-management” in his 1995 pipes|drums interview. Who was the better man manager between you and Bill?

p|d: Iain MacLellan talked about “man-management” in his 1995 pipes|drums interview. Who was the better man manager between you and Bill?

KE: Bill was far more dependent than me. He had a major supporting cast, and he managed to put these very strong musical personalities, together. When people like Michael Grey and Bruce Gandy left, Bill’s own musical creativity came more to the fore, which indicates to me that Bill, in the early years of his leadership, was a satisfier. He provided leadership, but accepted from the good plate of music that he had in front of him and kept people happy.

I didn’t have those human resources in the Clan, so I developed a sense of benevolent independence with close band personnel like Bob MacCrimmon and Noel Slagle to keep me on course.

p|d: Seems that maybe you kept people happy by winning prizes. Other pipe-majors might prefer to keep people happy by playing their music.

KE: A band at that level is a competitive animal, and it survives by winning. Clan MacFarlane’s good years were mighty good years, and as the band went through some lean years, we didn’t attract players, we started losing. When we didn’t attract players, the attitude declined as well. We didn’t have the music that the 78th had then. Yes, we kept them happy by winning.

p|d: What’s the single best pipe band performance you’ve participated in so far?

KE: Most enjoyable had to be the “Walking the Plank” medley at World Championships in 1998. That was a fabulous medley. It had all the qualities, percussion-wise, and musically, and it was one of those medleys where you just couldn’t go off the music. It’s the most recent best, but it doesn’t necessarily remain at the top in my mind. I can’t compare the performances, but Clan MacFarlane in 1972 at Fergus where we beat the Edinburgh City Police, and they were fresh from winning the World’s. We had a fabulous performance there, and that was our first year with medleys.

p|d: Those are ones that you’ve participated in. What about the best ones you’ve heard?

KE: It was the Shotts & Dykehead in 1974 at an insignificant contest at Meadowbank Stadium in Edinburgh, probably the day or the week after the World’s. They had a sound that was so resonant and vibrant. It was the epitome of everything good. The performances of the Victoria Police to win the 1998 World’s were a clinic.

p|d: What do you think the best qualities are that the pipe band world has to offer?

KE: The pipe band world provides an opportunity to explore avenues of music that you wouldn’t necessarily explore yourself. Most of today’s popular composers are sheer magic, and their music is played mainly in bands. Bands draw on so many musical resources.

p|d: What are the worst qualities of pipe bands or the pipe band world?

KE: It has to be the time commitment. I’m not one to sit around and waste my time, or waste anybody else’s time. I have high goals, and one of them is musical excellence, to the best of my ability. But the time commitment is a full-time mental occupation. It consumed me totally for forty years, and I am thankful to have escaped, to go back and have the time to do all these other things that I’d like to do.

p|d: What about the trade-offs that you made over the last 40 years? Any regrets?

KE: Because you’re so wrapped up in bands you miss much of the outside world. It’s very selfish because it takes you away from family, it takes you away from friends, and it cultivates a different social life. I have two grown kids, and there are big blank spots in their growing up that I know I missed. Do I regret it? No. I think everyone chooses their lot in life, but I think when it’s all said and done, you make these decisions and you run with them. I’ve found after forty years, that I don’t have a social group outside of piping. It’s really put a wedge into my life, and I think we all have to be conscious of that. And you don’t become really aware of it until it’s happened.

p|d: Do you think the pipe band world can get the better of people socially?

KE: Bands can be an obsession, and the higher you go the worse it gets. But people do this because they wish to. This is their life. If you were an amateur hockey player and you had a chance to play five games a week, you’d do the same thing. That’s what you want to do, and that’s how you fill your time. So, your hobbies sometimes become your obsessions. You could sit back in an ivory tower and say there should be more checks and balances built in, but they’re already there. You have the option of being in or being out, or going to a band with fewer demands.

p|d: If you had to pick one, which would you rather have? A pipe section of fast-fingered young players with lots of energy and drive, or a section made up of veterans with less accurate hands but with better tone abilities.

KE: I would suggest that, as bands quest for better and better music, they need the hands. You cannot do it without the mitts. The days of putting a band together based on your age, experience and blowing good sound are over. While sound is fundamental, you can manufacture it. But the raw technical ability of the players has to be there if the band’s going to go anywhere.

p|d: Iain MacLellan said that he’d much rather have tone guys.

KE: Iain is very correct in what he’s saying. He gave you his formula for success, but he took over a band that were career cops and didn’t have recruits at sixteen, seventeen eighteen years old. The people who were playing back then were a little bit older, and that was his formula for success, and I tend to agree with it then. But you didn’t see Iain playing the music that Field Marshal’s playing right now, for example.

p|d: If you plunked the Strathclyde Police of, say, 1986 vintage into the World’s right now, how do you think they’d fare?

KE: They’d win the MSR by a mile.

p|d: Would they fare as well in the medley, or on a concert stage?

KE: I don’t think so. It’s a different era, and the mindset of the piping community of that time was definitely tuned in to the traditional music that they were producing. The 1990s brought on bands like Field Marshal and Shotts. An example of a band that’s changed with the times more dramatically than anybody else, has to be Shotts from their march, strathspey, reel, jig and hornpipe medleys of the 1970s, to their music now created almost entirely for percussion. The pipe music exploits everything good that Jim Kilpatrick does with the drum corps, and their use of multi-voices in the mid-section. But the success of the Strathclyde Police of the 1980s versus today would rest with Iain MacLellan’s creativity.

p|d: What about the Royal Scottish Pipe Band Association? From the perspective of an overseas bandsman who has seen four decades of competing in Scotland, what should the RSPBA change?

KE: There has been so much demand put on the World’s Pipe Band Championships. Bands have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars attending these contests. Reorganizing the structure of the RSPBA to a “World Pipe Band Association,” as an umbrella group would certainly make the World Championships truly representative of the world piping geography, meaning that the World’s could be moved around. Glasgow would not be a permanent site. A token meeting with other associations after the World’s isn’t sufficient. You need an active, international association.

p|d: What are the consequences if they don’t do that?

p|d: What are the consequences if they don’t do that?

KE: International bands right now only see the RSPBA as the facilitator of the World Championships. The non-top-six Grade 1 bands travelling to the World’s year after year and putting that money up will stop going. The threat of not even getting through the qualifier causes bands to reconsider every year. It’s called a World Championship, and what’s made it great since the mid-1980s has been the consistent travel of SFU, the 78th Frasers, Vic Police, City of Washington, LA Scots. Last year was the first year that there were more international than Scottish bands. The quality of international performance has been a proven number for so many years, and so administratively, there’s got to be an international voice.

If the RSPBA is listening, they will be more receptive to international concerns. International reps need a more equitable voice in the decision-making process.

p|d: In your last interview, you said that judging at the World’s should become more international. Has that happened?

KE: I’ve seen no improvement whatsoever. There are two North American judges on the panel at the World’s – Bob Worrall and Ed Neigh. Those two were part of the first five who were grandfathered from Ontario. There’s been no positive impetus to bring other North American judges on to the RSPBA panel. If you go by representation by population, four of the Grade 1 World’s judges should have been from outside of the UK. It hasn’t changed since 1988. And there are no signs of it changing in the future.

Actually in 1988 there were five Ontario judges – Archie Cairns, Reay Mackay, Willie Connell, and Ed and Bob – on the RSPBA panel, so it has actually gotten worse. Three of the five are no longer used. If we had an international administrative group within the umbrella RSPBA, or World Pipe Band Association, then there would be an attempt to make sure that we have qualified judges from the international pipe band associations.

I would jump at the opportunity to judge those contests. What a great place to critique a pipe band contest, and contribute back to the pipe band community. Right now, there’s no physical chance of that happening. I’m only one of many around the world who would aspire to such a level.

p|d: What trends do you see occurring in the next, say, ten years?

KE: I hope pipe bands come to grips with the pitch. After having years of actually manufacturing the instrument, I question what can be done with the drone-chanter combination and how high the pitch can go. It depends on what the leading bands do. There are so many followers. If one band wins with a certain combination, then others follow.

In some cases, it’s had a negative effect on lower-grade bands. They’re using chanters that can’t reach that pitch. They’re sinking the reed so far, taping the top ends down so far, and losing their volume and sound quality.

The judges aren’t responsible. They’re looking at quality of sound. If they deem the quality of sound acceptable, they’re not going to dictate against it. It becomes a musical preference of the pipe-majors of the leading bands.

p|d: Is it the fault at all of the manufacturers coming out with new products, new higher pitched chanters? It seems a bit like the golf industry: hit the ball longer, farther, straighter, and it becomes a competitive problem on the PGA Tour.

KE: I’d hate to see a chanter that had Big Bertha across the throat! If Kenny MacLeod or Bob Shepherd came here today, just to cite two, and gave me a new chanter, and if I found favour with the clarity, the volume, projection, and the pitch, or any combination, I’d play those in a band. The manufacturers don’t have any obligation to the pitch. They’re merely putting out a product.

The mega-band has been established as the norm, with SFU winning the World’s with 18 to 20 pipers. The centralization of the big band in major centres will continue. Pipers will commute to play at the top levels.

p|d: What about band size? Where’s that heading?

KE: The mega-band has been established as the norm, with SFU winning the World’s with 18 to 20 pipers. The centralization of the big band in major centres will continue. Pipers will commute to play at the top levels.

There’s going to have to be some influx of ideas in changing the contest requirements. I can see some experimentation with more concert-type formats for contests, as more bands try to get onto the concert stage. I don’t know where the medleys are musically going. Have we explored everything that’s possible?

p|d: What three major things will change in the next five years?

KE: There will be fewer bands at the Grade 1 level. I don’t see Canada going beyond seven or eight bands. The trend’s certainly not going that way. We’re also going to have to address the local Highland games situation and the impact that the World’s has on them. If we don’t tend to our own house, then we don’t get the support group from here. We’re going to have to look at our Highland games presentation and encourage the bands to support what they have locally.

p|d: Now that you’re semi-retired from competitive piping, what are your thoughts on teaching? Does a great teacher have to have been a great player?

KE: No. To be a superior piobaireachd player would indicate that you have the knowledge and ability to play. Do you have the skill to transfer that musically to a student and bring it out in the student? Some do and some don’t. The qualities of communication become really strong. John Wilson had the playing credentials, and he could certainly put a tune across. The world is full of great players, but there are far fewer teachers of the art. A good teacher must be competent and also a good student. A good teacher has sat on both sides of the fence and knows what the student needs to hear.

p|d: On that note, you’re booked solid for months with workshops and things all over the place. What makes you such a popular teacher?

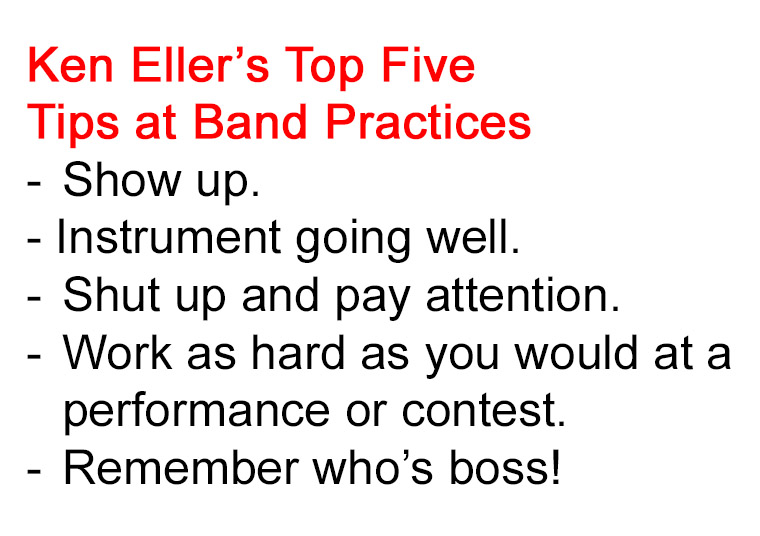

KE: A lot of the work I do is with pipe band players. Band players rarely get critiqued. They realize their playing can improve, but they don’t know how. Enter the teacher with patience and time to devote. You always think positively, about the music and where you can improve; things that students do that are good. If you have a positive approach in anything you do, you’re bound to gain acceptance.

p|d: If you could do it all again what, if anything, would you change?

KE: I would have joined the 78th Frasers in 1988. I had 10 years there, but if I could have had 14, it would have been that much greater. In hindsight, if I had joined them in 1986, I could have got that World Championship!

p|d: But then it might not have happened . . .

KE: Touche! You got me! Seriously, I wish I had stayed with John Wilson for more piobaireachd. I’m playing catch-up right now. A regret would be that I didn’t pattern myself after some of the other players that have combined a successful pipe band career with a successful solo career. I love teaching. I had a 32-year career in teaching mathematics for a living, and yet I didn’t really teach private lessons from 1970 to 1990. I did workshops and schools, but I didn’t create a player base around the Niagara peninsula, and that would have contributed to the longevity of the Clan MacFarlane.

If you ask, what lies on the horizon? Well, it’s starting right now. I’m playing catch-up, filling in the gaps in my musical life, the things that I set on a back burner as far back as 1970 and only now I’m being able to come back and enjoy, with piobaireachd being probably a passion, but never past the enjoyment stage. I’m working through a few tunes; going back to my Bob Nicol and Donald MacLeod tapes. It’s just great, because I have the time for it.

The possibility of getting back into the pipe band scene always exists. I’ve had a few offers.

p|d: In leadership or just playing?

KE: I’ve had both, but I don’t want any part of the leadership thing. That’s a really tough go. And as the last 10 years have proved, being a back-ranker is fabulous. There’s always an opportunity. The playing days aren’t finished. I feel like I am just starting again.

What do you think? We always welcome your thoughts via our Comments feature below.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider subscribing or donating to the nonprofit and independent pipes|drums so we can keep creating exclusive, original content like this. If you have already subscribed, thank you for your support.

NO COMMENTS YET