I want to do *that*

Editor’s note: for many years, “Blogpipe” was a more or less personal blog. In hindsight, it was often overly self-indulgent, as most blogs were then and still are. Blogpipe also raised and tackled many previously taboo topics. Maybe 10 years ago, Blogpipe was wound down, replaced with editorial/opinion pieces clearly listed as such. You can still find Blogpipe entries in the archive database.

I hope that this piece isn’t taken as self-indulgent. It’s hoped that it inspires readers to contribute their own stories of becoming unlikely pipers or drummers. And by unlikely, I mean maybe someone like me, having the derivation of a name changed at Ellis Island, no practice chanter thrown in the crib by a piping parent, or not having the opportunity to join a piping/drumming teaching program at school.

We’re publishing this fairly lengthy piece on my late father’s birthday, September 20th. He would have been 100. He played a huge role in my piping and my writing and everything else, really. It felt right to publish it today.

If you’d like to contribute your own story of how you got started with the pipes or pipe band drum, please feel free to contact us. We’d love to hear your own extraordinary story.

I want to do that

By Andrew Berthoff

My mother, Tirzah Margaret Park, was Scottish, born in Tillicoultry, raised in Glasgow, a graduate of Glasgow University, a lover of Robert Burns and Scots culture. But it was my father, American-born of Eastern European Jewish and Mayflower Pilgrim descent, a professor of American Scots-Irish immigrant history, who loved all things Scottish.

My mother seemed to tut at tartan and the shortbread clichés of Scotland and, along with them, the bagpipes. I would not say that she disliked the pipes. Unlike many émigré Scots who get weepy at the sound of the pipes and the sight of a pipe band, my mother paradoxically distanced herself from bagpipes, as she distanced herself from many things that she felt were beneath her.

My dad, Rowland Tappan Berthoff, absolutely loved Scotland and all its tribulations and trappings. I remember him playing Jimmy Shand accordion LPs. He rejoiced when PBS’s Scottish “Galloping Gourmet,” Graham Kerr, came out with an authentic Scottish spurtle, basically an oak stick with a thistle-like handle, for stirring porridge. He ordered one immediately, presumably by letter-post with a check, delighting when it arrived. He couldn’t wait for my mother to use it.

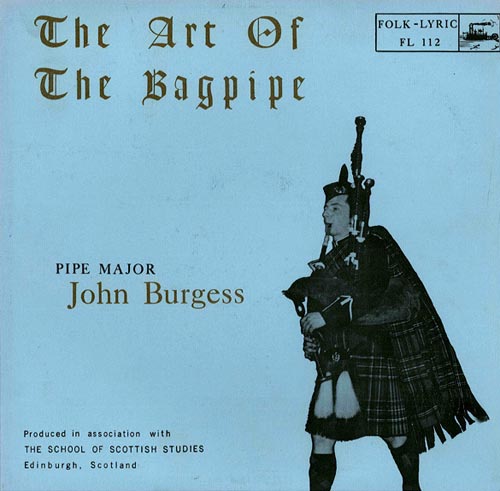

My dad purchased and loved piping and pipe band albums. He had the good sense to buy a rare LP made by a very young John D. Burgess, The Art of the Bagpipe. On it, Burgess plays “Lament for the Children,” “Leaving Lunga,” “The Geese in the Bog,” and other music that would later inspire me when I literally played the grooves off of it. I still have the album.

My dad purchased and loved piping and pipe band albums. He had the good sense to buy a rare LP made by a very young John D. Burgess, The Art of the Bagpipe. On it, Burgess plays “Lament for the Children,” “Leaving Lunga,” “The Geese in the Bog,” and other music that would later inspire me when I literally played the grooves off of it. I still have the album.

My dad met my mother after he was a postgraduate student on a Fulbright scholarship at Aberystwyth University in Wales. He had completed his Ph.D. at Harvard under the guidance of the famous American immigration and culture historian Oscar Handlin. He encountered Tirzah Margaret Park on the boat to the Isle of Canna, part of Scotland’s Inner Hebrides. They were each on their own, as good fortune would have it, their families connected with the then-owners of Canna, John Lorne Campbell and Margaret Faye Shaw.

I recall my dad’s account of their meeting on the little bonnie boat, speeding its way past Skye. He said he knew she was smitten with him because she kept inadvertently kicking some sort of bilge valve as they talked, causing it to gush water in a Freudian manner. As an historian, my dad loved to find meaning or a reason or cause for just about everything.

On their own, the new couple could frolic uninterrupted on the near-deserted five-mile island, with only the sheep paying any distracted attention.

They swept one another off their feet, and within a few months, were married. My mother would be on her way with my dad to settle in New Jersey, where he had been offered an assistant professorship at Princeton by the then Dean of Humanities, Robert Oppenheimer of Manhattan Project atomic bomb fame.

Some years later, after the New Jersey births of my brother, Tom, in 1960, and my older sister, Margaret, in 1962, they moved to St. Louis, where my dad accepted a full professor of history post at Washington University in 1962.

I was born in September 1963 and grew up in University City, the suburb first west of St. Louis City.

As a family, Scotland was always present. My mother pretty much lost any Scots accent she might have had after moving to the States, but I was aware that other people were generally aware that she wasn’t American. My dad might have promoted her being Scottish, and, indeed, my mother never took out American citizenship until the 1990s, when it was somehow expeditious.

Jimmy Shand, a spurtle, his beloved collection of Victorian Paisley shawls, and a few lengthy and convenient trips to Scotland were a significant part of my dad’s existence.

Jimmy Shand, a spurtle, his beloved collection of Victorian Paisley shawls, and a few lengthy and convenient trips to Scotland were a significant part of my dad’s existence. The first trip was for a whole year, in 1965-66, where my dad had a teaching post at the University of Edinburgh. We had a house on Morningside Drive, of which I don’t remember much. But my earliest memories in life are from that trip.

The first is of my brother, my dad, and me in raincoats on the deck of the ocean liner that took us to the UK. Tom and I had made paper airplanes, so we were testing them into the roiling Atlantic in the teeming rain.

My other memory is walking from a tunnel of wisteria or some other vegetation on the path up to Tighard, the guest house my family occupied on Canna. I only recall a gate and a flash of sunshine and perhaps the floral, grassy scent of the island. If one’s lucid life starts with a memory, mine began that year, and so it is that the origins of my world are about as Scottish as they get: driving rain and mist overlooking the ocean; flora and fauna of an idyllic Hebridean day.

Our other lengthy trip to Scotland was the summer of 1974. My dad had completed his historical work, An Unsettled People; Social Order and Disorder in American History. An advance and royalties from publishers Harper and Rowe meant that we could take an unprecedented non-working real vacation as a family.

The six of us (with the addition of my sister, Clarissa, in 1971) made the epically slow but still thrilling train journey from Union Station in St. Louis to Penn Station in Manhattan. Pre-Amtrak, it was with Pennsylvania Central on “The Spirit of St. Louis” route. I recall being stalled in Illinois or Indiana for many hours due to a freight train blockage because the tracks were owned by and gave preference to, as they still do, non-passenger trains.

We had two family “Pullman” sleeping rooms, the boys in one and the girls in the other. Apart from the delays, I remember seeing thick swarms of lightning bugs decorating a black Midwest night. My dad was getting very excited at a famous horseshoe bend, I believe in Pennsylvania, that allowed those at the front or rear to see the whole train. The sight thrilled him, as it thrilled me, too, when my own family took Via Rail’s “The Canadian” from Toronto to Vancouver in 2005.

After a visit to Long Island at my parents’ friends seemingly palatial house, our family and our 13 suitcases – one of which was accidentally and not a little comically left on, and miraculously recovered from, a Long Island Rail commuter train – we left JFK on my and my siblings’ first plane trip, arriving in Heathrow. I can’t remember how we got to Glasgow – no doubt by another train – but we settled in for a few days with my mother’s old university chum, the well-known painter Nanzie MacLeod, at her house on Clarence Drive, and her four daughters, who made my 10-year-old heart beat a little faster.

From Glasgow, we boarded the West Highland Line from Queen Street station for Mallaig, then to Canna for six weeks. The latter six weeks we spent in Edinburgh, in a house on Mayfield Road.

My dad was determined to have us visit every castle ruin in the country. From Tantallon to Craigmillar to Dunnottar, where every rampart was walked and every dungeon was progressively more boring torture. My favourite part of the Edinburgh stage of the trip was discovering “Asterisk” comic books; creating little darts with an empty pen tube, pins and a bit of yarn; and on the High Street buying tiny plastic soldiers that my brother and I played with endlessly.

My dad, for whatever reason, purchased a practice chanter and a Logan’s Tutor book from Gordon Stobo’s Glen’s Bagpipe Makers on the High Street.

On a visit to relatives in Glasgow, I also discovered music of my own, which told me there was more to it than Jimmy Shand, military pipe band records and my mother’s love of the Beatles, Stones, and Simon & Garfunkel. It was a copy of Elton John’s Don’t Shoot Me, I’m Only the Piano Player. The song “Daniel” hooked me, as it does today, and my passion for discovering new music on my own started.

The other thing that happened was that – and this finally gets us to the more salient part of the story – my dad, on a whim, purchased a practice chanter and a Logan’s Tutor book from Gordon Stobo’s Glen’s Bagpipe Makers on the High Street.

My dad got it, I would imagine, with the tacit but fervent hope beyond hope that one of us would take up piping, which we, of course, had zero intention of doing. He would never impose anything on his kids. My brother was heavy into learning classical guitar, and my sister was becoming a flautist. I was told by the unforgettable Hiram Martin, a music teacher with an intriguing toupee, that my teeth were too crooked, and learning the trumpet with the braces he predicted would be coming would not be possible. So I was assigned the snare drum to learn in my final year at Flynn Park Elementary School.

But we kids would fool around with the chanter, laughing at its absurd kazoo-like sound. I don’t remember associating it with the bagpipes, but more as a curiosity that entertained my more-Scottish-than-most-Scots father.

We returned to St. Louis in early September. I was a day or two late for the start of the school year. It was a traumatic change to Brittany Middle School, a horrible place more suited to reform than learning. For an 11-year-old, missing just a few days at the beginning of a new year at a new school – to which I had to take a bus – was an eternity. All year, I felt as if I were catching up.

We would occasionally fool around with it as a joke, and one day left it on the couch, and one of us kids of course sat on it. The chanter snapped at the neck. Reminiscent of his fits of panic imbued with rage, my dad was beside himself. This precious piece of Scottishness was broken.

But the practice chanter and the tutor book had came back with us to St. Louis. The chanter literally kicked around the house. One day fooling around with it the chanter was left on the couch, and one of us kids of course sat on it. The chanter snapped at the neck. In one of his fits of panic imbued with rage, my dad was beside himself. This precious piece of Scottishness was broken.

Testament to his undying hope that one of us would one day express interest in learning the pipes, he glued the thing back together. I remember being intrigued that the colour of the chanter’s wood was noticeably different on the outside, and it was clear that the black was painted on the tan-coloured material of the product. Later, I would realize that Stobo of the coveted Glen’s shop sold my unsuspecting father a tourist chechke chanter made in Pakistan, which he foolheartedly believed was the real Scottish deal.

I don’t know what he used for the repair, but after the adhesive set up, the chanter tended to ooze this sticky material at the joint. He might have had to re-glue it at least once since it inevitably would have been broken again. I don’t know. But the chanter, along with my dad’s determination, survived.

The year wore on. I learned to despise drumming, not because of the instrument, but because of Mr. Klauzmeier, the music teacher, who was a very proud German. I mean, he had the Brittany band play “Deutschlandlied,” the German national anthem. I don’t know. It was weird. But he never seemed happy with anything I did on the snare drum, the timpani or even the triangle. He would specifically tut-tut at me for the blown breaks and things at even the most straightforward passages.

Thinking about it, he followed a trend. My original music teacher, Ms. Presgrave, whose big hair, odoriferous perfume and Grandmaster Flash heels, always seemed ready for the St. Louis version of Studio 54. She showed her despair when I kacked up the solo drumming flourish in the Flynn Park band’s rendition of Quincy Jones’s “Theme from Shaft” at the outdoor school concert, enthusiastically attended and photographed by, yes, my dad while my mother was at home looking after Clarissa or something. Ms. Presgrave’s withering look of disdain is seared into my retinas.

After attending the Edinburgh Tattoo the previous August, I noticed the pitch of the pipe bands’ snares to be extremely high-pitched. I liked that. Once back in St. Louis, I took the drum key that came with the used red sparkle Ludwig snare drum my dad sourced for me from Baton Music and proceeded to try to crank down the heads and the snare as tight as I could in an attempt to achieve that less rattling sound. I had no idea what I was doing, and amazingly nothing broke. As I did in the fifth grade, I didn’t have to lug my drum to school, so Klauzmeier was never the wiser.

The summer break in 1975 was welcomed. It had been a tough school year, and I was already plotting to get rid of drumming. If you’ve been to St. Louis at any time other than, say, a week in January or February, you will know that the place is consistently scalding and humid. The summer months are a nonstop swelter, temperatures consistently above 90 with humidity to match. My father, raised during the Depression and convinced the next great crash could happen any day, would rarely turn on the air conditioners that otherwise decorated a few windows. So our University City house was like a New Mexico sweat lodge, except we weren’t paying for the experience.

But in July, for reasons unknown, a Highland games was being organized in the far-reaching and newfangled St. Louis suburb of “Earth City.” This opportunity excited my dad to no end. Despite what might have been the hottest day in American history, he packed all of us into our band-aid-tan 1962 Studebaker wagon. He took us to the games, which were held on a broiling black tarmac parking lot.

And now comes the most bizarre thing and the heart of the story. For some reason, I was inspired. Maybe it was the sound. Perhaps it was the spectacle. Or I might simply have been trying to please my dad. But I expressed interest in learning the pipes.

In addition to the Shriners parade band and the much better but fledgling Meeting of the Waters Pipe Band from St. Louis, at least two bands were brought in from Toronto: the Toronto Gaelic Society and the Toronto Scottish. Each band was wearing full number-one dress, replete with tunics, spats, and plaids. The works. Again, they were doing their best to play on a tarmac in 110-degree heat with the unrelenting sun beating down on their pale Ontario faces.

And now comes the most bizarre thing and the heart of the story. For some reason, I was inspired. Maybe it was the sound. Perhaps it was the spectacle. Or I might simply have been trying to please my dad. But I expressed interest in learning the pipes. This I remember clearly. “Can I learn that?” is what I said to him. Not, “I want to be a piper,” or “I love that music,” or anything else. “Can I learn that?” was all it took for my dad to scurry off to find someone to teach me that.

And here is the most fortunate part: he wound up talking to the better of the two St. Louis bands, the one that wanted to improve, to learn, to eventually compete, and not the band of venerable good-time Charlies who wanted to be a spectacle and make some noise for charity.

Whomever he spoke with from the Meeting of the Waters (an excellent name for a band, named for the tune but also the confluence at St. Louis of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers) gave him the location of their next practice and encouraged him/us to come along.

It was in a bank branch building in Kirkwood, Missouri, another St. Louis suburb. It must have been the following week since my dad’s excitement percolated over the days. We drove to the place in the Studebaker. The band occupied a strange larger meeting room area on the second floor of the little building.

I remember entering the room with my dad. Various band members were sitting around, getting out their gear, and, like every other band practice of any musical genre on earth, chatting until someone got something going.

The pipe-major was one Vincent Victor “Vic” Masterson. He did the teaching. I was sent to an adjacent room, much darker, my dad accompanying me. I don’t recall any other students. Just me, my dad and Vic.

We, of course, came armed with my sticky twice-broken Pakistani chanter and the Logan’s Tutor. This version was updated by Captain John MacLellan, complete with photos of the great man showing how to hold things. More on that later.

Victor Masterson didn’t need no tutor book. Our Vic was a talker. The first lesson was mostly a lecture about his take on the origins of piping. I recall that he waxed on about the “Picts and the Celts,” and I’m sure it was all my historian, pernickety dad could do not to set the guy straight about accurate history.

When it came to the playing part of my first lesson, Vince/Vic placed his thick fingers on his chanter and had me do the same. I remember wondering how anyone could play well with ample digits rubbing together. Were chafed fingers a piping risk?

The band probably didn’t expect us to return. Still, we were back to the bank for the following Saturday and the inexplicable G-gracenote. Vic’s hammy hands hammered his engraved-silver-mounted Lawrie chanter as he emphatically demonstrated what to do. I tried to unstick my G finger from my gooey quasi-instrument.

But – and I will always be grateful for this – he knew the basics. He understood the purpose of gracenotes and the perils of false-fingering. We started with the scale and that crazy pinky down on C and the three bottom-hand fingers on the chanter for the top-hand notes. Sure enough, Captain MacLellan’s hands in the photos in the tutor book corroborated this. I was sent away to work on the scale. My pedantic pa railed on about the Picts and the Celts for days.

The band probably didn’t expect us to return. Still, we were back to the bank for the following Saturday and the inexplicable G-gracenote. Vic’s hammy hands hammered his engraved-silver-mounted Lawrie chanter as he emphatically demonstrated what to do. I tried to unstick my G finger from my gooey quasi-instrument.

I kept at it and kept on learning things. My first tune was “Scots Wa’ Hae,” whatever that meant, and then learned “The Hawk That Swoops on High,” a fine 3/4 march that had all kinds of troublesome throws and shakes and things. Eager to show off my questionable talents, my dad had me play my chanter at a Christmas party at one of their friend’s homes, which would have certainly repelled their pre-teen daughter, who held my interest for a few unrequited years.

I wished then that I had a drum set or a Fender Stratocaster and not a Sheesham wood Pakistani practice chanter with which to impress her.

At some point, though, I was nearly abandoned as a student. Vic brought in his teenage son to learn along with me. I think he was Vincent Victor Masterson II or III. It was plain to me that V. Victor Vince II had no genuine interest in learning the pipes. He’d been thrown into it, and, no matter how he performed in lessons, his dad was hard on him.

Along the way, I found myself in the middle of a tense father-son standoff, which wasn’t conducive to my learning. Thanks to the guy’s son, I was something of an orphaned learner. When I mentioned to the band that I played the drum at middle school, they promptly strapped a giant Premier Super Royal Scot on me and let me hammer away in the parking lot, to what avail, I still don’t know. I guess they wanted drummers, and had I been more enthusiastic, I might well right now be a pipe band drummer.

Fortunately, I was rescued from the piping scrap heap, and others in the band taught me, and to them I will always be appreciative.

As luck would have it, the now-deceased Gordon Speirs would sometimes travel through St. Louis for his business selling artificial athletic tracks to schools, and he would occasionally have workshops with the band.

An Englishman, Gordon was a terrific player. I believe he gained a few prizes in his limited solo career at the Northern Meeting. His father-in-law was the legendary Bob Hill, of tune-title ceilidh fame. He had a fantastic set of MacDougall of Aberfeldy drones and a genuine Sinclair pipe chanter. He regularly let me play his pipes to experience how a bagpipe was intended to operate and sound like. Because he thought it would be a good challenge, he somewhat radically gave me, a second-year learner, “Abercairney Highlanders” and “Donella Beaton” to learn as exercises. Gordon saw promise in me, and he always had my back at various competitions in the Midwest. He was pivotal in me becoming a piper mainly because he saw something, and encouraged me to push myself.

(A few years later, I’d get more instruction from Gordon, travelling by Amtrak to his home in Milwaukee on several occasions when I was a student at Macalester College in St. Paul. He and his then wife, Catriona, put me up for the weekend, listening to me play and giving me more challenges in between shouting on their adventurous young son, Ross.)

He also had a questionably bright idea. Gordon knew that the Grade 1, multi-time World Champion Muirhead & Sons were struggling for pipers. I was now 14 or 15, and Gordon introduced me by phone to the legendary pipe-major Bob Hardie, telling the great man that he had a piper from St. Louis who could help his band. Uh-huh.

I remember being on the phone with Hardie, ridiculously seeing myself as a callow teenaged member of one of the greatest bands in history, wearing all that double-breasted number-one dress as Bob looked after me in . . . wherever the band was.

Hardie was at a loss for words. He ultimately said, “Well, we’re full up for pipers at the moment.” Full up. He let me down easy. It wasn’t that I was an unknown teenager from Pipingnowheresville, USA, who had babysitting written all over him; it was that his rapidly disintegrating band was full up.

(In 1984, again, I would approach Hardie in his bagpipe-making shop at 24 Renfrew Street, Glasgow, to ask him to do a pipes|drums Interview. Once again, to my great disappointment, he gave me the brush-off.)

I can’t imagine what my dad thought or if he even knew about the scheme to play in Muirhead’s. In 1979, after competing as an amateur at Maxville for the first time and hanging out after the contest in the sweaty beer arena with members of the great Clan MacFarlane Pipe Band, one of their members drunkenly told me I should come up and play with them. Move to Buffalo! Easy!

So, another cockamamie scheme was hatched. I would become a member of the mighty Clan MacFarlane, possibly the world’s clubbiest of bands. I’d live with someone – not sure who – in Buffalo all summer as they nurtured my skills. I wrote to Pipe-Major Ken Eller with something between a job application and a demand.

Like Bob Hardie, Eller let me, a 15-year-old from St. Louis, down gently in a hand-written response. A few years later, both my dad and Ken revealed that they had talked and agreed that a teenager hanging with hard-partying Clansmen was just a shade half-baked.

After several years in Scotland, I would play with Ken Eller in the 78th Fraser Highlanders when I moved to Toronto. I would get weekly lessons from Captain John MacLellan, at his house, in Edinburgh, watching those fingers. I would become friends with John D. Burgess. I would get a few solo piping prizes from Bob Hardie, who I’m sure never twigged that I was the kid on the phone wanting to play in his band or the cub editor asking for an interview.

Looking back, all of this happened within about four years. It seemed an eternity then. These days, it’s the length of a gracenote.

It shows just how relatively random piping can be, especially for those with no piping lineage, much less a name like Berthoff. A few fairly random decisions change everything. It might start with an enthusiastic American father buying a Pakistani practice chanter, resolutely repairing it a few times as he holds out hope that one of his kids might express interest.

One thing leads to another, and it can start with a simple serendipitous sentence.

I want to do that.

Related

NO COMMENTS YET