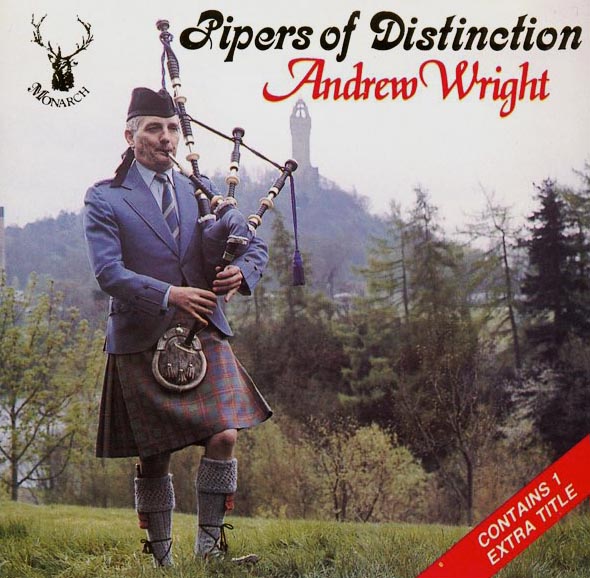

‘Don’t give me a Polaroid. Develop the tune. Give me clarity.’ – pupils pay tribute to the late Andrew Wright

![Andrew Wright, 2017. [Photo pipes|drums]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2022/11/Wright_Andrew_Aug2017_02.jpg)

He touched countless piping lives, tirelessly imparting his knowledge to virtually anyone, regardless of playing ability, who wished to learn.

The most amazing thing was that, with the exception of days-long workshops and summer schools around the world, he never charged a penny for private instruction. He maintained that it would not be right or ethical for him to take money when his own teachers – Robert Brown, Peter R. MacLeod, Donald MacLeod, and Robert Nicol – didn’t charge him.

Andrew Wright did what came naturally to him: he taught. His only reward was what he himself gained from his teachers: the sharing of knowledge and the promotion of music.

We asked several of Andrew Wright’s more prominent pupils if they might share a few thoughts on their teacher, and we were pleased and honoured to receive the following tributes, plus one from the editor of pipes|drums.

Donald MacPhee – one the greatest American-born pipers, he has lived in Scotland for almost the last 30 years. A winner of the Highland Society of London Gold Medal at Oban and countless other awards, Donald MacPhee is a full-time reedmaker and adjudicator for both solo piping and pipe band competitions.

I first met Andrew at a piping school in Wyoming in 1995 or ’96. He taught piobaireachd and I did the light music. Free time is very limited at these schools, as the students always come to you for extra help or tuition at all hours of the day. Andrew held a piobaireachd “workshop” one evening that I sat in on and that’s really where our friendship started.

I moved to Scotland in 1997 and at the age of 31 the majority of my piobaireachd was from Jimmy McIntosh and Mike Cusack. Andrew was very gracious with his time and expertise. I was able to get lessons in the morning, which really suited Andrew, and many of those mornings the noon hour came ever so fast.

“Don’t give me a Polaroid. Develop the tune. Give me clarity.”

His greatest influence on me was in tune presentation, he would explain using the analogy of a photographer to a photo. “With some photographers you can literally see the soul of the person in the photo, and that, Donald, is the expert photographer, Edward Curtis, best known for his photographs of North American Indians or another great photographer, Ansel Adams. These men took stunning photographs for their time period. Don’t give me a Polaroid. Develop the tune. Give me clarity.”

I never saw him use a book or the musical score yet he would be conversant in styles or different interpretations of tunes or settings. He was a man with a remarkable memory.

Jimmy and Mike would conduct you through your tunes. When playing for Andrew, if your shape was coming out of focus his hands moved in the air as if he was moving a helium-filled balloon, and continued to move that way until your focus returned and his hands settled back to a resting position.

Past President of the Competing Pipers Association and the Piobaireachd Society, solo and RSPBA Adjudicator, recording artist, writer, educator, beloved husband and father.

Andrew Wright left piping in a better place.

John Cairns – an owner of the coveted true “Double,” winning both Gold Medals in the same year (1999), John Cairns shares the feat with his teacher at the time, Andrew Wright, who achieved the distinction in 1970. Now retired from solo competition after winning rafts of awards, he’s very active as a judge and as the pipe-major of the Grade 2 Peel Regional Police Pipe Band.

I felt a tremendous sense of sadness and loss when I read about Andrew’s passing. This man had such a huge impact on me, my playing, and my appreciation for our great music.

I remember judging with him and another fellow at a piobaireachd contest a few years back. It was a huge contest and a true test of one’s ability to retain your focus. Near the end of the contest, the third judge started to drift away. By the time the piper reached the taorluath doubling variation, he was asleep in his chair.

When the piper finished playing, the applause from the enthusiastic crowd startled and woke the judge, who then (in his fog) stood up and started clapping along with the audience. Andrew was aghast with this and turned to me with a look of horror on his face and exclaimed, “What the %#*^!” Thankfully I was able to control myself from bursting out laughing and we finished the contest.

In the back room when we were deliberating the prize, the third judge thought that the player whose performance he slept through should be considered. Andrew calmly responded and said, “Oh, no, no, it was a good tune, but was quite slow and could easily have put someone to sleep.”

This is just one example of the professionalism and class that this man had as he was able to deal with the “elephant in the room” without embarrassing the judge.

I will forever be grateful and thankful that he not only came into my life, but was so kind and generous with his knowledge, time, and willingness to help me.

The piping world lost one of the greats. Andrew was not only an outstanding musician and teacher, but his passion for piobaireachd was contagious and inspired many players from around the world, myself included.

My deepest condolences to his family.

Jim McGillivray – now retired from solo competition, Jim McGillivray has both Gold Medals, the Northern Meeting Clasp, a Glenfiddich MSR and dozens other top prizes to his name. He’s been a professional piping teacher for most of his life, and the author of several best-selling instructional works.

I first heard of Andrew Wright when he won his Gold Medals in 1970. I was captivated by his “Nameless – Hiharin Dro o Dro” and learned the whole piobaireachd by ear from listening to the tape endlessly.

The first time I met Andrew Wright was at a summer piping school in Sackville, New Brunswick, in 1981. He was the chief instructor, and I was an assistant instructor. Part of the duties of the chief instructor was to offer instruction to their assistant. This Andrew dutifully did, and he did not slough it off. He would spend nearly the whole lunch hour with me going over the year’s set tunes for Oban and Inverness, then we would rush to the dining hall, wolf down lunch, and start afternoon classes.

I was always grateful for that sacrifice of lunch time he made to go over tunes with me. For the next few years he was a boon to my playing. We met in person when we could, often by tape. His knowledge of the tunes was unparalleled and he had a great way of communicating musical expression by words and not just by singing. He was a piobaireachd treasure.

Ben Duncan – possibly Andrew Wright’s longest-tenured regularly-scheduled student, Ben Duncan is one of the world’s most successful solo pipers of the 2000s. Recently retired from a long career with the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards, Duncan enjoyed one of his most successful competition seasons in 2022, winning numerous overall trophies around the Scottish games circuit.

I was devastated to hear of the passing of Andrew Wright last week. Andrew has been a huge part of me for over 22 years (over two thirds of my life) and I am grateful for all he has given me. I had been going to him for so long that there was almost a telepathy between us. I’d know exactly what he was going to say before he said it.

I began lessons with Andrew at the City of Edinburgh Music School in 2000. I was a young ambitious boy at the time and he stripped back my playing, rebuilding it from the ground up. A tough pill for me to swallow at the time, but I knuckled down and now owe him the world for the amount of time he invested in me, not just in Piobaireachd but in my light music too. He’d often say “You’re not . . . you’re Ben Duncan so play like Ben Duncan. Never mind the rest of these guys, we’ll play the way we play.”

I was fortunate enough while at school to have a three-hour lesson with Andrew every week. An hour on Light Music, an hour on Piobaireachd and an hour on the pipes. We got through an astonishing amount of material. When I joined the army I then went for lessons as-and-when I was home. We’d sit and get through 10 or so tunes at a time, Andrew never once opening a book, his encyclopedic memory of Piobaireachd was unbeatable. We would only be done when Isobel would appear with a cup of tea. Some days we could be going through tunes for close to four hours. He was extremely generous with his time.

A true gentleman and private man, he would never refer to any of his other pupils during lessons, making the whole experience solely about you and your piping.

Anyone who had the pleasure of a lesson with Andrew would know that he was a man who loved an anecdote or phrase to get his point across. One that particularly stuck was his “Frank Sinatra” when describing how to correctly deliver the subtlety of a cadence. He’d say “Frank Sinatra didn’t sing it – I did it my way, he sang it – I did it myyyyyyy . . . way” the other phrase he would use was “I am going to the . . . shops.” Simple but ingenious! I had a fair amount of Frank Sinatra throughout the years.

Another he’d use for highlighting the pulse beats in compound duple time was the six-syllable word Spi-ri-tu-al-it-y and pipe-er, drumm-er for simple time.

A true gentleman and private man, he would never refer to any of his other pupils during lessons, making the whole experience solely about you and your piping. So much so, that I went for years without knowing that people I’d see week-in, week-out around the competitions were going to Andrew for lessons, too.

At times, when the prizes weren’t coming but I was content with how I’d played, he’d say, “These guys probably won’t understand what we’re trying to do, you’ll be playing over their heads.” He was so invested in trying to produce a unique product and made it very clear to “stick to your guns, this is how we play it.”

I will be forever grateful for his guidance and generosity throughout the years and will miss him dearly.

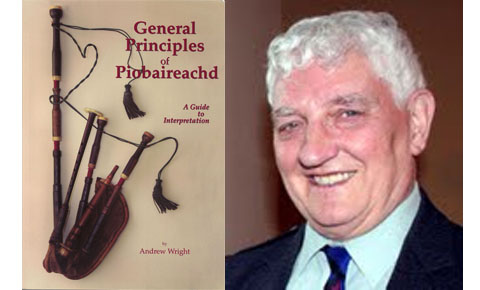

![At home in Dunblane in the room where Andrew Wright taught dozens of pupils over the years, committing thousands of hours to free instruction. [Photo pipes|drums]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2022/11/Wright_Andrew_1990.jpg)

I was deeply saddened to hear of the passing of Andrew Wright. First and foremost, he was a wonderful, kind and generous man who was devoted to his family. He was also an exceptional piper and a lifelong student of piobaireachd; always eager to learn and enhance his knowledge of this great music. I feel privileged that Andrew was my piping tutor for the best part of 25 years. Little did I know that my departure to the southern hemisphere in early 2018 for 18 months would mark the end of my regular lessons with him.

My journey with Andrew began at 14, shortly after playing in front of him at an RSPBA junior contest in Glasgow. He must have been reasonably impressed with my performance that day as it was only a couple of weeks later that my dad and I were invited to visit his home, with a view to me attending him for lessons. I am so grateful that he found the time to take me on, as he was still working, was in high demand as a teacher and was returning to competitive piping. From that point onwards, I embarked on an amazing piping journey with a very special individual and I never looked back.

His teaching of piobaireachd was both magical and captivating. He had an incredible ability to convey exactly how he thought a tune should be played.

I was extremely fortunate that my family home in Bridge of Allan was only four miles away from Andrew’s house in Dunblane. Every week, I would make the short journey “up the road” and was always warmly welcomed by Isobel and him. It was, without doubt, the highlight of my week. No matter how bad a week I had experienced at school, university or work, I was always able to escape from the outside world and immerse myself in my piping lesson with Andrew. His teaching of piobaireachd was both magical and captivating. He had an incredible ability to convey exactly how he thought a tune should be played.

The smooth and elegant delivery of expressive musical piobaireachd playing was always the desired goal. It was Andrew’s belief that the treatment of the “short notes” was central to achieving good piobaireachd playing.

A “light touch” was also an important prerequisite. During one particular lesson, Andrew pulled a pipe chanter out of a drawer that had recently had a silver sole attached. The sole had been made by a local silversmith and was initially quite plain to the inspecting eye. However, closer inspection revealed the engraving of a butterfly. Upon asking Andrew why he had chosen a butterfly design, he replied by asking me to consider how a butterfly flew, to which I replied that they flew in a light and gentle manner. “Exactly!” was the reply and I was then informed that the master piobaireachd player should strive for the touch and finesse of a butterfly. To this day, I think of a butterfly every time I play a piobaireachd.

In addition to piping, Andrew had a great passion for walking. I would often bump into him on one of the many paths or country roads linking Dunblane and Bridge of Allan. He enjoyed walking holidays with friends and I believe that he completed many of the classic walking routes and passes in the UK. He also travelled extensively overseas, in particular North America. Consequently, we shared many jokes about the number of air miles that he must have accrued over the years! He was an avid reader and was very fond of North American history.

Over the years, Andrew told me many wonderful stories. He clearly had a great admiration and affection for the “Bobs of Balmoral,” who he went to for lessons, and many of the stories relating to piobaireachd would involve some reference to these famous pipers.

During one story, Andrew informed me that a beautiful clock sat within the home of one of the Bobs. Shortly after their passing, Andrew met another of their pupils and was promptly informed that they had been left the clock. The pupil then proceeded to ask Andrew what he had been left. His reply was, “Oh, they left me far more than a clock, they gave me all their music,” pointing to his head with a smile. And my goodness did he retain their music and teaching to the benefit of all those who had the privilege of hearing him play.

I, like many others, owe Andrew so much and I will cherish all the time that we spent together. His passing is a great loss to the piping world but his legacy will live on through his many pupils around the globe.

Andrew Berthoff – editor of pipes|drums.

Andrew Wright saved me. Exasperated and a bit depressed after landing to live in Scotland for at least the next year, I was having zero success after a few months finding a top-grade band to join and a true piobaireachd authority for regular lessons. By an extraordinary story of good fortune (that I’ll tell another time), Andrew eventually welcomed me into his Dunblane home for regular instruction when I was a 20-year-old third-year exchange student a few miles down the road at the University of Stirling.

“Aye, come by the house,” he said when I called him from a campus payphone. I made my way to Dunblane by bus, used a map to find his house on a dark night in late October 1983 and, practice chanter and tape recorder in hand, nervously rang the doorbell. He didn’t know me at all, but he made time, as he did with so many pipers eager to further their piobaireachd proficiency.

That first lesson was a test. I was aspiring to win the Silver Medal. The requirement in 1984 was six tunes of one’s choice. Instead of lazily going through piobaireachds that I already knew, Andrew gave me all eight of the tunes set that year for the Gold Medals. Those tunes happened to be shorter that year, so we managed to go through all of them quickly and, after about three hours of getting their gist, recording each, he wrapped up the lesson, saying, “Okay. Give me a call when you have these memorized.” He probably expected never to see me again.

I dropped whatever university studies I had, skipped classes, and did whatever it took to memorize all eight of them in a week. I called him the next Sunday to tell him I had them off.

He sounded surprised, and we arranged another lesson and it was then that we got down to business. He seemed to realize that I was serious and had at least a small bit of talent and commitment.

“Aye. You’re welcome because, you know, we’re all in this together.”

If I had to choose one word to best describe Andrew Wright it might be “Aye.”

It was the beginning of an incredibly rewarding relationship. He and Isobel were generous beyond compare. Andrew would regularly offer to give me a lift not only to and from lessons, but to piping competitions and recitals. He would never accept money for anything, saying, “Aye, just go out there and play well.”

His teaching was all about the music and the “shape” of the tunes. Andrew would talk about the space of phrases, the give and take of the timing, the holding of notes “as if you were on the edge of a cliff” to create tension, cutting doublings of variations rather than simply playing at a faster pace – concepts new to me then but which have guided my playing ever since. About pleasing the judges, he would often say, “Aye, they might not know what you’re doing, but they’ll like it.”

I can’t claim to have had the depth of instruction from him that people like Ben Duncan and Innes Smith enjoyed, but we went through perhaps 60 or 70 tunes over the course of a few decades.

If I had to choose one word to best describe Andrew Wright it might be “Aye.” He seemed to start every response with “Aye.” He was positively attuned to being positive about piobaireachd.

I last saw him in 2017. We got together in Glasgow for a final interview. He had slowed noticeably, and I took the opportunity again to say how much he helped me and how greatly I valued our friendship.

In his familiar manner, he simply smiled and said, “Aye. You’re welcome because, you know, we’re all in this together.”

Andrew Wright’s funeral on November 1, 2022, was private, reserved for close family and friends. His life’s commitment to teaching will live on through generations forever. Our sympathies are with Andrew Wright’s family.

NO COMMENTS YET