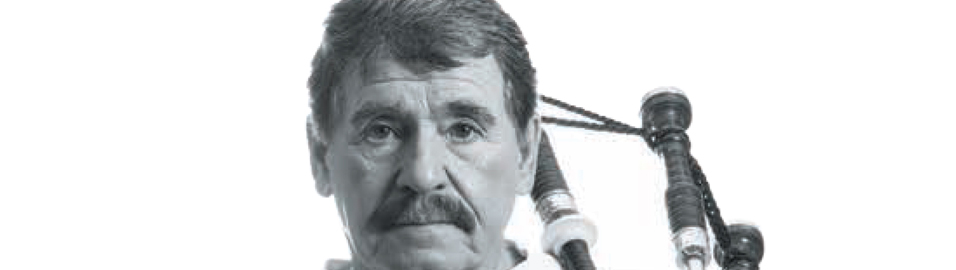

Bill Livingstone: the pipes|drums Interview from the Archives – Part 2

We bring you the second and final part of the May 1993 pipes|drums Interview with Bill Livingstone, who sadly passed away in February.

In Part 1, he discussed in great detail his piping roots, a hiatus from competition while pursuing a law degree, and the state of the art as it was more than 30 years ago. In Part 2, he becomes even more outspokenly opinionated, as was his character. You will read about how little has changed in many regards over the last three decades.

His views are just as inspiring, pithy and insightful today.

![Bill Livingstone competing in the Clasp at the 2005 Northern Meeting. [Photo pipes|drums]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2025/04/LivingstoneBill-NorthernMeeting2005.jpg)

Part 2

pipes|drums: Let’s turn now to solo piping. The John MacFadyen summer schools in Ontario were intense piobaireachd training grounds, producing such notables as Ed Neigh, Jim McGillivray and John Goodenow. To you, what were the sessions all about?

Bill Livingstone: At that time in the early 1970s, the rage in Ontario, and actually all over North America, was summer schools of piping. To call the MacFadyen school a school of piping is to give it a term that it doesn’t deserve. It was much, much more than that. There was no reveille in the morning, and there was no dividing of the classes into seniors and intermediates and into boys and girls, and all the rest of it. There was a very practical hands-on attack by MacFadyen himself on all of the people who were there, and everybody got MacFadyen to himself every day for a period of time.

I often say piping is like malaria, and I had a relapse.

p|d: And at that time you were considered a senior player?

BL: Yes. I had come back to piping in 1969. I had been at the CNE [the Canadian National Exhibition, a celebrated three-week event still held in Toronto in August, which used to feature the Intercontinental Pipe Band Championships] with Lily. I had not played a bagpipe in 10 years. I had finished my articles and was in my bar admission course. We heard the 48th Highlanders playing in the band shell, and I hadn’t heard a bagpipe in years. I often say piping is like malaria, and I had a relapse. I bought a practice chanter and I looked up John Wilson’s number in the phone book because I remembered his name from when I was a kid, and T called him and I asked him if he remembered who I was, and he did, and I asked him if he would give me lessons, and he would, and I went to my first serious lessons as an adult in 1969 in Octo-ber, and I played at my first piobaireachd competition at the indoor games in April.

I spent a couple of years with John, and I went around the games, and I was not awfully successful. But I did run into John MacFadyen at the Thousand Islands Games and he gave me third prize in the piobaireachd competition playing “The Lament for the Viscount of Dundee,” and told me that with any kind of work and attention I might be able to make something of myself as a piper. I was over the moon. I went down to my first summer school, and in the space of a week I got about a dozen piobaireachd. When you got a piobaireachd, you went over the score with MacFadyen singing, and then over on the practice chanter, and sent away in the morning, and you were expected to return for your afternoon session and play the whole tune on the bagpipe under conducting from him. And then you got a second tune right after that.

He was as an instructor little interested in theory and abstraction and whether this was the Cameron school or not. What he was most interested in was, by the sheer force of his will and his personality, dragging the music out of you. I still have tapes of me playing for him in 1972 or ’73 at these schools, and playing music that was well beyond me. I had no idea what I was doing. I was just following this powerful personality who scared the wits out of everybody in a way that made you play in a way that you didn’t dream you could play. But you took away all these tapes and instruction and this inspiration, and I think that everybody who was there got some part of that to some degree or another. He was tremendously inspiring as an instructor, and he really inspired a love for piobaireachd and the music and a passion that is very hard to get from any other kind of personality.

p|d: How much of your style of piobaireachd playing can be attributed to John Wilson, John MacFadyen, or Captain John MacLellan? Or do you prefer to think of the way you play ceol mor as simply Bill Livingstone’s?

BL: I think that all piobaireachd players eventually gravitate back to the teaching roots that they’ve had. John MacFadyen influenced me probably more than others. I had a lot of tunes from Donald MacLeod and Captain John MacLellan, but those sessions were the polishing of an already-formed player. For example, Donald MacLeod was particularly good at “Lament for the Laird of Anapool.” Donald took me through that tune with great care. I play the tune as I was taught it by Donald, but I also play the tune as I was fundamentally inspired to play by John MacFadyen.

p|d: I remember your recollection of John MacFadyen on how to play “A Flame of Wrath”: “You don’t hang about while the buggers are burning.” Your approach to piobaireachd is often described in terms such as “brisk,” “forceful,” and, simply, “fast.” How do you respond to such descriptions?

BL: Maybe it is forceful, but when I hear recordings of great pipers from the past, I’m very taken with how the short notes are short without being hacked and the long notes are long. This gives an impression of driving a tune, but it isn’t really, it’s extracting the most out of a piece of music. My father always had an expression: “Even grief has to proceed at some sort of tempo,” which I think is true. In the band when we play a slow air we try never to dirge it, no matter how poignant the melody might be, and I believe that of piobaireachd, too.

I think that there’s far too much slow playing and too much careful, cautious playing with no risk taken with the music. When I first came on the scene as a solo piper, there was a lot more individual character, I think, in the piobaireachd playing than there is now. In earlier times, there was a more individualistic approach to piobaireachd playing, and people were more willing to take a tune by the scruff of the neck, as MacFadyen used to say, and give it a good, bloody shake. Even some lamenting tunes need a good boot in the right place.

p|d: MacFadyen was one of the select few, I gather, who was able to experiment with tunes with great success. It seems to me that you use the same sort of approach you use in your piobaireachd playing as has gone to your band. Will the biographer of Bill Livingstone in 2050 say, “Bill Livingstone carried what he learned from John MacFadyen in piobaireachd over to his pipe band.”?

BL: No, he’ll more likely say, “See Livingstone, W., footnote 200”! [laughter] That’s not a stretch to make that comparison; I think it’s true. What we’re talking about here is a basic approach to musicality. Most of us have a fundamental idea about music, and it wouldn’t matter if you were talking about jazz, or Vivaldi, or rhythm and blues, or piobaireachd or pipe bands, you would probably bring the same basic sensibility to your music. There are so many things that can be done internally with rhythms and portions of melodic lines that are often ignored, because people, since we thrive in a competition, are unwilling to take risks and express their true musical feeling about a line of melody.

p|d: What’s your favourite piobaireachd and why?

BL: How do I feel today? What do I want to do? Do I want to listen to something? If so, then my favourite tune is “The Unjust Incarceration.” It’s a tune I don’t even play. It’s an amazing piece of music, and I love to hear it. If I want to be majestic and enjoy a wonderful major key melody, then I want to play “Lament for the Earl of Antrim.” It’s a stunning composition. It’s amazing that men who might not have been able to write their own name were able to compose music of such power and majesty and use so few notes to achieve that, and it’s never boring. Do I feel bloodthirsty and aggressive? Well, then I’d look to “The Vaunting.” It’s a very difficult thing to say what your favourite piobaireachd is because there are just so many wonderful compositions and every one suits a different mood and a different need that you have.

p|d: Which tunes do you think you are associated with?

BL: That’s a judgment that’s not for me to make, but I can tell you that my performance of “Anapool” in 1981 at Inverness is often mentioned to me partly because it’s such a towering piece of music and it’s so difficult technically, and it’s so rarely played, and when it is played it really sticks in people’s minds.

p|d: You are the only person in history to win a Clasp at Inverness and take a Grade 1 pipe band to a World Championship title. Given you’re the only one, are piobaireachd and pipe bands generally incompatible?

BL: No, they’re not even slightly incompatible. It all depends on what kind of pipe banding you’re doing. If you’re playing in a pipe band that isn’t interested in producing fine piping, then perhaps the piobaireachd player has little to contribute there. But, on the other hand, the good piobaireachd player wouldn’t be in a band that has that kind of ethic. So, I don’t think for a moment that pipe bands and piobaireachd are in any way incompatible.

p|d: On to the dreaded political side of piping. Would you ever sit a test to become a piping judge?

BL: It’s a topic that has bothered me for a long time, and I’ve thought a great deal about it. In order to understand my position, you have to look at two things: first, my general philosophy on the issue of tests and, second, at what has happened historically in Ontario.

When the subject of qualifying adjudicators became a hot topic in the mid-1980s in the PPBSO, I felt that we should be very, very careful about setting in place a system that could have a counterproductive effect, that could have the effect that I could see had happened in Scotland to a large degree. Over there, the examination and qualification system seemed to make it possible for people who were, by anecdotal evidence, or according to the opinions of people, “knew what they were doing,” didn’t really belong on the bench to judge major competitions. This was particularly so in the pipe band circle. At the same time, there were a significant number of eminently qualified people who, for whatever reason, had not sat the examination and were therefore not certified and were therefore not qualified to judge standing on the sidelines.

My initial reaction to the whole business was that there is far too much bureaucracy in piping and pipe bands, and I decided that this is something we ought to proceed with great care, because I feared that what was going to happen was what had happened in Scotland: good people were being kept off and people unqualified would, by reason of having sat and passed the examination, be admitted to judging.

To turn to the history of what happened, there was a large committee struck to examine the whole question of certifying judges, and it had a lot of very good people on it. I can’t remember them t all, but there was certainly Ed Neigh, who sat as the chair at the outset, Bob Worrall, Willie Connell, Jim McGillivray, Reay Mackay, Ken Eller, and me. We had some initial meetings to discuss this question.

I recall that I was one of the only members of that committee who was not in favour of the idea and was trying to encourage people to think of some other way to do this. And we had maybe two or three meetings that didn’t get very far, but we were doing some serious talking on this very serious subject. But then the Society’s committee to deal with certifications just seemed to disappear, and what had been struck as a committee was replaced with what apparently was another new committee to which almost everyone on the first committee was not invited. In short, it became apparent that the Pipers’ Society had an agenda: that we will set up an examination system and a certification system and this committee isn’t dealing with it in as expeditious a way as we would like, so we will get a committee in place that will.

Examinations were apparently designed and a certification on process was set up, and none of that process involved the members of the first committee except those few who were in the second committee. This presented some real difficulties because I felt that I had some significant points and thoughts to contribute to the ind thing. It doesn’t embarrass me to admit that my nose was somewhat out of joint over this, and I felt insulted. While I don’t pretend to speak for others, I’m sure I was not alone in that feeling.

Having said all that and having ruminated about the subject for a long time, I think that, by and large, it’s a sound thing to have some sort of admission criteria to judge. [He reflects on the subject for a moment] I think that’s okay and that it makes some good sense, and on balance, I support the principle of admission criteria, examinations and certificates for judges.

It is apparent that the fears that I had have all come to pass. There are eminently qualified people who ought to be on that panel who are not, and there are people who, if “those who know” were asked, should not be judging but have been qualified.

What bothers me most about it is that if you look at the panel of people who are qualified according to the PPBSO in one of your recent issues, it is apparent that the fears that I had have all come to pass. There are eminently qualified people who ought to be on that panel who are not, and there are people who, if “those who know” were asked, should not be judging but have been qualified.

But the question is, would I sit a judging test, and I were particularly keen on judging—which at the moment I am not—would do it? The reason I’m not anxious to judge is a personal belief that you should run with the hare or run with the hounds. I’m still an active soloist and bandsman and I personally feel uncomfortable judging one week the people whom I’ll be trying to beat the next week. It’s a somewhat different question, though, when judging outside of your bailiwick—I’ve done some of that, and I don’t feel bothered in those circumstances.

My endorsement of judging tests and certificates should be taken with the reservation that I still think there has to be a better way to select judges. There must be more control over who’s invited. Nobody fails the British Army’s Pipe Major’s course at Edinburgh Castle because those who are asked are very carefully screened. Somewhere along the line, that kind of thing has to happen here; it can’t be open to everybody to go and sit a judging test because it’s not a hard thing to pass a judging test, I think. But the ability to distinguish merely good playing from very excellent playing, requires some very special skill and knowledge and experience, and a judging test does not do that. People who have a good general basic knowledge of all forms of the music should decide who ought to be asked to sit the test. That is the initial screening step that ought to be taken that hasn’t been taken.

I have heard it argued that tests and certifications will help sort out the judges with character and integrity from those who lack the qualities. That of course is pure nonsense, since no judging test can measure these things.

My final thought on this subject has to do with the question of integrity. I have heard it argued that tests and certifications will help sort out the judges with character and integrity from those who lack the qualities. That of course is pure nonsense, since no judging test can measure these things.

p|d: In order to be a qualified judge do you have to have in your past a competitive record of walking the boards, of playing to a very high level?

BL: [A long, thoughtful pause] Pipers and drummers generally have respect for the opinion of someone who has demonstrated, through performance, that he or she is a capable performer. I really think that the first requirement ought to be a good record in piping. In order to avoid controversies and to avoid the kinds of sniping that we hear in Scotland, it’s a pretty good guarantee of acceptance by pipers that a judge has proved themself to be a good player, and how do you do that? By a career of piping and achievement, and performance.

p|d: How do you respond, then, to highly respected judges who never competed, like Seton Gordon, Archibald Campbell, Sheriff Grant, and James Campbell?

BL: You make a terrific point, because I cannot say that James Campbell and Archibald Campbell haven’t made a staggering contribution to piobaireachd; it’s absurd to suggest that they don’t know good piobaireachd playing. But there is a distinction between piobaireachd scholarship and other kinds of piping expertise. Piobaireachd is as much an intellectual art as it is anything else, and the kind of people you are talking about who have devoted a lifetime of study to the art of piobaireachd bring a sensibility to it that the pure performer doesn’t. I don’t think that I’m being intellectually dishonest or inconsistent in recognizing that in pio-baireachd there is real room for that kind of person.

p|d: For years, you were very active at PPBSO meetings, voicing your opinions, sitting on committees, and even organizing complex unions. What, if anything, caused you to distance yourself from the politics of piping?

BL: I don’t know that anything really drove me away from it. just simply had my fill of it. It’s a really thankless task doing all the administrative stuff that goes with piping and I found it particularly bad that so much of the organization is done by and large by people who have not been seriously involved as performers and competitors and participants. And so, there is not much understanding of what goes on from the competitor’s point of view. And I found that after a while, it became very tiring.

p|d: Will piping politics ever destroy the music, or has it already started to happen?

BL: I have, for one reason or another, been involved in so many awful political controversies in my piping career that I have to say that you raise a very good question. I mean, a band disqualified for three contests over a tempest in a hat [a controversy that started because Livingstone, when he was in the General Motors band, did not wear a hat in massed bands, and the band was subsequently suspended for three contests after an altercation as a result of the incident]; the awful political uproar at Inverness in 1974 over the concealed tape recorder [Livingstone was originally placed second in the Gold Medal competition only to have his prize taken away after an American enthusiast produced a tape of the contest that showed he had made an error in his tune]; the disqualification of the Frasers at Georgetown a few years ago for being late to the line. There have been a lot of decisions like that that have affected me or my band directly that are incomprehensible from the players’ point of view. That’s perhaps why I feel so much like an anarchist.

I think there’s far too much control and bureaucracy and carry-on in the piping world. Let’s just go and enjoy it and play and have a good time. I mean there’s room for rules, but there has to be room for some discretion and flexibility, too.

p|d: Do you see the politics getting worse?

BL: To be honest I stay away from it so much that I don’t really see any of it. I really stick with my band which I really love to be around. Apart from that and my own solo piping, I don’t really need anything more in piping. I’m happy to stay away from all of the political brouhaha and just leave that to others and get on with the playing.

p|d: Is the Society too political?

BL: The PPBSO basically runs Highland games, and the result is that in Ontario you don’t have any bagpipe or pipe band competition that has the slightest degree of individual character. Every one of them looks exactly the same from start to finish. The solos start as the sun comes over the mountain at eight in the morning, the frost or rain, or whatever happens to be lashing down, and at 1 pm everybody stomps up and down and plays in the massed bands, and then the contest takes place, and then the massed bands takes place depending on whether or not the needs of the games committees’ beer tent prevail or not, somewhere between 6:00 and 8:00 at night. Where is the rule for individual character in these things?

Go to a games in the United States. Every one of them looks different, because every one of them is permitted to run their contest as they see fit, provided that they make the basic concessions to the prize money and the judging and the travel money and that sort of thing. What is the PBSO doing announcing the prizes at the Maxville games? What have they had to do with the organization, staging and funding of those games?

p|d: What do you have to say about pipers who claim to know what “tradition” is in pipe music?

BL: If we had been hidebound by that kind of thinking, we’d never have piobaireachd as we know it, we’d never have gone to the fiddlers to create piping strathspeys, piobaireachd playing might not even exist. If Alan MacDonald ever gets to publish his study on the relationship between Gaelic song and piobaireachd, we’ll see that there is a distinct connection between those two things. One borrows from other forms of related music. For anyone to suggest that if you don’t play in a “traditional” way then you’re not playing well. It’s absolute wrong-headed thinking. Music is never stagnant.

I mean, if it were, then it’s a set piece; it’s a museum piece. Music changes and develops constantly. To say that there is a tradition in pipe bands that we can’t violate is to fly in the face of what we know about it. The McAllister family invented the modern pipe band no more than fifty years ago, and to be saying now that there’s a tradition that we can’t violate is crazy. We’re in the process of creating it, we’re making it up as we go along. As long as you try to respect the reasonable boundaries of idiom, then almost anything goes.

It’s easy to do nothing. You’ll risk nothing and you’ll gain nothing. But if you’re always trying to seek some fresh way to do things, then once in a while you’re going to stumble and it’s going to be bad, or it’s going to be not very tasteful, or it’s going to go too far.

p|d: What is the idiom you’re talking about?

BL: It’s basically Celtic music. Listen to the rhythms that the Irish players play on bodhrans—they’re so similar to what good pipe bands can play, the same kind of rhythmical drive to the thing. There is so much to be borrowed and cross-fertilized. It’s easy to make a mistake and to go too far, to be tasteless and, in anticipation of letters to the editor, I admit readily that the Frasers have on more than one occasion done that. But that’s okay, there’s nothing wrong with that, it shows you’re making an effort. It’s easy to do nothing. You’ll risk nothing and you’ll gain nothing. But if you’re always trying to seek some fresh way to do things, then once in a while you’re going to stumble and it’s going to be bad, or it’s going to be not very tasteful, or it’s going to go too far. And we’ve done it, and I can assure you we’re going to do it again. It just happens, it’s part of the package.

p|d: There appears to be a balance between competitions and concerts and recordings as avenues for expressing the band’s music. How did that balancing act come about?

BL: We had developed a good and entertaining repertoire that we played competitively. It attracted the attention of people who wanted to hear that kind of thing portrayed in some arena other than a competition platform. We basically just stumbled into doing concerts. We did a couple of them over here on a fairly small scale, and then the folks at Graham Memorial came along with the suggestion for Ireland. That really changed the band in a fundamental way because we had such a wonderful time doing the concert, we were so well received, and they were so gracious and appreciative. It just made being a piper in a pipe band a different experience from merely going and competing.

With the success of the concert and the album it became obvious that this was the kind of pipe band entertainment that people would be interested in attending. So a lot of invitations began to appear for us to do concerts. It’s a really important part of the band’s operation, attending and doing these concerts. It’s satisfying musically, and they’re entirely different from competition and yet in many ways they’re more difficult and more stressful because the obligation to sustain performance over two and a half to three hours is onerous to say the least.

We’re also lucky to have all of this repertoire and all of these great composers and people who are able to source good material, even if they don’t compose it themselves. So we have a really broad interesting repertoire of music which we can play both competitively and on the concert platform. I think that talks about what the band is about, which is that you can broaden the horizons of what you do in a pipe band and yet not violate any idiom because there’s not very much that we do in concerts, with the exception of the odd piece with electronic drum kits and that sort of thing, that you couldn’t pick up and put in the competition arena and be perfectly at ease with.

p|d: What goals do you still have?

BL: I want to be a better piper. There’s never, ever a time in your piping career when you can’t be a better player and do something to enhance your skills and your musicality, and as long as you’re piping and devoting your energy to that then you’re advancing everything. In terms of specific achievements, I want very much to win the Silver Star at Inverness, and as a pipe-major, I want to notch at least another five World Championships. [He knocks on the table.]

Age is irrelevant. What is important is your determination to play at a very good level and your willingness to devote the energy and time to it.

p|d: How much longer can we expect to see you clouding the boards with talc and leading the 78th onto the field or into the studio?

BL: I don’t have any thoughts of retiring. That wasn’t the case a year or two or three or four ago, but that, as I reflect on it now, had less to do with my interest in piping than it did with some unpleasant times that were happening in the pipe band, that gave me a very negative feeling about piping in general.

Now that all of that unpleasant internal stuff has been resolved, and the band is a wonderful and happy place to be again, I cannot remember being more enthused about piping at any time in my piping career than I am right now. Age is irrelevant. What is important is your determination to play at a very good level and your willingness to devote the energy and time to it. So, the answer to your question is, I hope for as long as I play well and as long as I’m having a good time in sight. doing it. I don’t know when the end will be, but right now it’s not in sight.

Bill Livingstone continued to compete successfully at the highest levels of solo piping and pipe bands well into his seventies. During that time, he composed, arranged, and published music, recorded a musically adventurous album, developed a series of commercially available archival piobaireachd recordings, and wrote a 300-page memoir.

For more by and about Bill Livingstone, use the pipes|drums search tool to discover the many pieces by and about him from our nearly four decades of nonprofit work.

NO COMMENTS YET