Bill Livingstone: the pipes|drums Interview from the Archives – Part 1

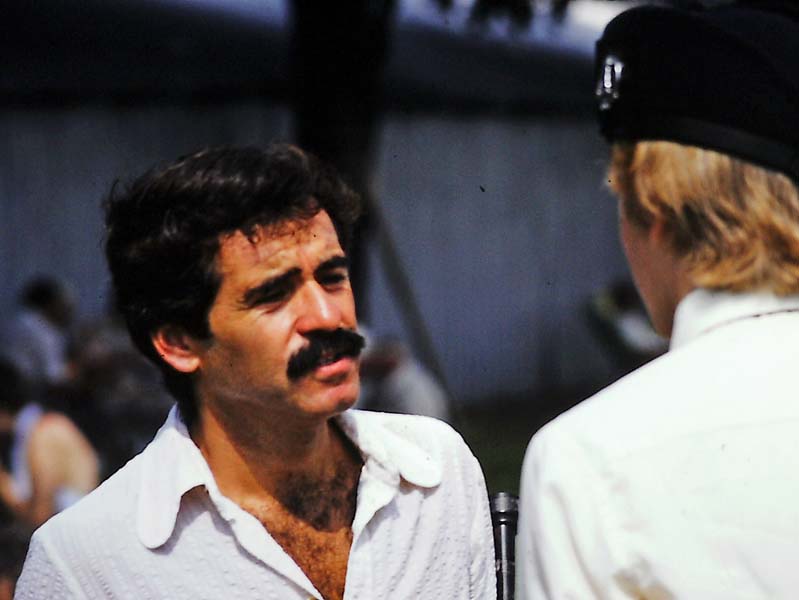

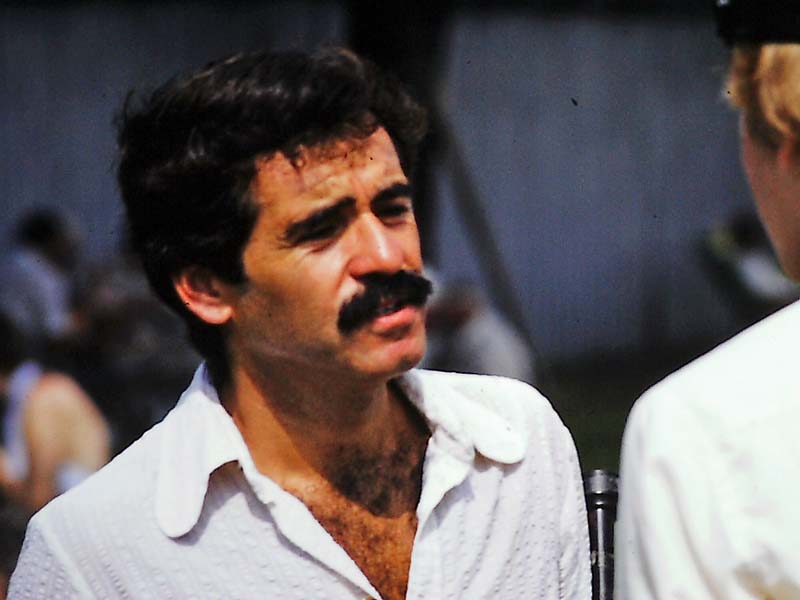

![Bill Livingstone competing in the Silver Star Former Winners MSR at the Northern Meeting, 1984. [Photo Rowland Berthoff]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2025/03/Livingstone_Bill_InvernessMSR_Sept1984.jpg)

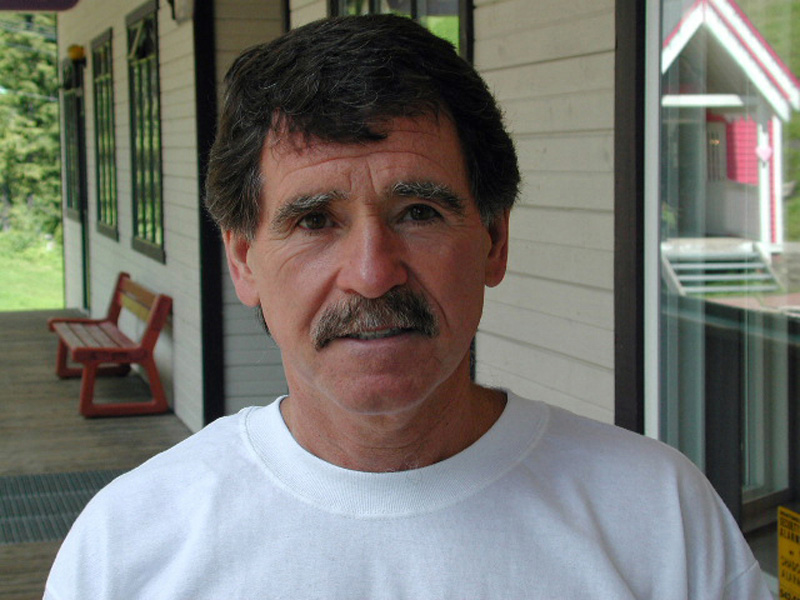

In May 1993, we met with him at his home in Whitby, Ontario, for an extensive interview. Only six years removed from making pipe band history by leading his 78th Fraser Highlanders to the 1987 World Championship, Livingstone had turned 51 on March 20th.

The band still managed to gain top-six prizes at the World’s, but hadn’t seriously contended for the big prize since 1988, when one piping judge put the band back far enough to keep them a repeat victory. (The “what-if one judge difference” can usually be said at any pipe band competition.)

Details of Livingstone’s life, which were included in the introduction to the pipes|drums Interview, can be found in the pipes|drums obituary, and, of course, in his memoir, Preposterous, Tales to Follow, published in 2017.

The day was unseasonably hot when we got together in May 1993. We set up in the screened porch at the back of his craftsman-style home on several acres, overlooking a swimming pool, with a picturesque westerly valley view.

It was the first interview I’d done with a piper or drummer who was not only still competing but one whom I was both competing against in Ontario solo events and with as a piper in the 78th Frasers. It was an odd feeling for both of us, and I remember Bill being visibly anxious.

I remember him fidgeting throughout the conversation with four or five small conical steel spikes. I didn’t know what they were for—perhaps to elevate high-fidelity floor-standing audio speakers—but he kept rearranging them as we spoke, in a line, in a group, perfectly separated in various formations.

He spoke carefully and deliberately, recognizing that the interview would be part of his legacy. This was true to form; Bill did nothing haphazardly. Everything was carefully planned, if not rehearsed, even though it often presented as an aloof, seat-of-the-pants character.

Looking back, the interview is an excellent, if not vital, mid-life snapshot of Bill Livingstone. It’s fascinating to see where he was at the time, and where he imagined things going. His life for the next 32 years would be just as interesting and accomplished. There were concerts to deliver, albums to make, prizes to win, events to judge, places to go, books to publish, milestones to celebrate.

I wish that we could have gotten together for a second interview. We talked about it frequently, but for whatever reasons, didn’t manage it. It’s okay, the remaining items he wanted to discuss were covered in Preposterous.

Here, then, is the May 1993 pipes|drums Interview with Bill Livingstone, which we will run in two parts.

Part 1

pipes|drums: A good way to commence an interview: How did it all begin?

Bill Livingstone: My dad was from Ayrshire and left, I think, when he was about 19 or 20, to escape the fate of the coal mines, which he had been working in from the age of about fourteen. He and my uncle John had lessons from a man from the Cumnock area, Davie Hendry, a piper of considerable skill. He taught them musical notation, which I think was relatively uncommon in those days.

Dad came to Canada in the midst of the Depression, and there was little work anywhere. He ended up in the middle of Saskatchewan, working on a wheat farm. Then work became available in Sudbury, Ontario, with International Nickel. He started Ranald, my brother, playing the bagpipes, and I cannot remember a time in my childhood when bagpipes were not some sort of a part of almost daily life. I was not so much instructed as I was finally tolerated; I just wouldn’t leave them alone. He would be instructing my brother, and they’d be playing the practice chanter, and I was really taken with the idea of the practice chanter.

When I was about four, I got a boy’s practice chanter, and I’m told that I could read pipe music before I could read words. By the time I was 10 or 12, I had developed a large repertoire of all of the old classic piping tunes, and by the time I was in my early teens, I had the Willie Ross Collection committed.

My dad was my only teacher really until I was about 27, apart from a brief period of time when I was about 14 when I had gone to Sault St. Marie Highland Games, and the great John Wilson was judging, and there was a Ceilidh there after the games. I was pressed into playing, and I remember playing in front of John Wilson, and he said to my father that, with proper tuition, I might be a reasonable player.

My parents sent me to a school in Toronto for my first year of high school, and I lived in the home of an elderly gentleman who was something of a piper and a fanatic for repairing bagpipes. I lived there for about three months in the fall of my fourteenth year and went to school at Western Tech in Toronto, a huge school and terrified out of my mind taking the streetcar to school and knowing nobody.

But my salvation was that I had John Wilson on Saturday mornings, and I joined the 48th Highlanders as a boy piper. That lasted for about three months until my parents came down to visit me one time in this autumn period of that year and discovered the lady of the house blitzed on the cooking sherry, trying to set the house on fire with the gas stove and yanked me home by December. From that point on, I didn’t have any other instruction except from my father until I went back to John Wilson, when I completed law school.

p|d: You were away from piping for about ten years to pursue your law degree at Osgoode Hall in Toronto. That was at a time when many pipers hit their competitive stride. But you were able to come back in only a few years and win the Gold Medal at Inverness. Did you consciously set out to get your professional career underway first and then achieve your piping goals?

BL: No, it was very much chance. My father had bought my mother a piano when I was about fourteen and I would be up every morning at four or five trying to figure out how to make some music out of it. So I went and did the wise thing and bought Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis records. I sat and memorized all the licks. I started to play rock and roll, and I just sort of grew away

When I went to Oban and Inverness the first time, John MacFadyen had to explain to me the point that there were Gold Medals to be won, and who presented them, and what they stood for, and that there were set tunes.

p|d: Did you have any idea about Gold Medals and achievements in piping at that age?

BL: In 1971, when I had already been to Scotland once, George Campbell mentioned the name Donald MacPherson to me, and I didn’t have any idea about whom he was speaking. I was a complete ignoramus. When I went to Oban and Inverness the first time, John MacFadyen had to explain to me the point that there were Gold Medals to be won, and who presented them, and what they stood for, and that there were set tunes.

When I was young I wouldn’t say that I played in more than half a dozen bagpipe competitions as such, a few in northern Ontario. I didn’t really understand what the competition thing was about at all. It’s very, very isolated in northern Ontario, particularly in those days. My only influence was my dad.

p|d: You were talking about playing the piano as a teenager in Sudbury in the late 1950s and the early ’60s. What role do you think that contemporary musical background has played in your approach to music, particularly pipe bands?

BL: [He ponders the question] I think that my interest in other kinds of music opened my ears to things other pipers—who are strictly pipers and haven’t played other kinds of music-don’t ever get the opportunity to experience. Learning to play blues or any type of music, you have to understand rhythmical patterns. I just think those rhythms became a part of my musical consciousness.

p|d: You will be forever associated with the 78th Fraser Highlanders, but you were pipe-major of Caber Feidh, City of Toronto and General Motors. How much were those bands the training ground for what you would do at the 78th?

BL: I think it’s important for people who want to become good pipe-majors to recognize that it’s a long learning experience to figure out how to run a pipe band in a way that’s consistent with your own personality and also achieve some kind of musical goal that you’re happy with. And it took me a long, long time to get those skills worked out and to apply them. Those bands were a great training ground for me because you have to have an opportunity to start. By the time I had a pipe band of my own, which was really Caber Feidh/City of Toronto, I had established something of a reputation as a soloist, and that was attractive to the guys in the band to have me come and run the pipe band. I also was known, I think, for being open-minded about what kind of music could be played. I can recall those days in the mid-’70s when Caber Feidh was beginning to experiment with different ways of putting together music. I was very supportive of that, and I was very vocal about the fact that I liked the kinds of things that they were doing. So, they saw a combination of a player who had developed some skills as a soloist and was sympathetic to the kinds of musical ethics that they had.

p|d: Who was the pipe-major of Caber Feidh then?

BL: I believe it was after Chris Anderson retired, and I think Gerry Quigg had the band for the hiatus of a year or two, and Gerry was not at all keen on running the whole show, and they were looking for somebody to fill that slot. That’s how I got there.

It was a really good experience because you got an opportunity to make a tremendous number of mistakes, and it’s the only way you can learn how to do the job of a pipe-major. It’s very much a trial-and-error kind of thing.

p|d: It must also have been perfect timing with the advent of the medley and a little bit more freedom for bands to experiment musically. I’m thinking of the Guelph Pipe Band, and a few bands in Scotland, to some extent, in the mid to late ’70s, starting to do different things.

BL: It was a ready-made thing for somebody like me because by and placed us as low as he possibly could have. If he could have the time I got to Caber Feidh they had already experimented with making “MacIntosh’s Lament” work as a centrepiece for a medley.

So I walked into that situation with a lot of that thinking already in place, and it was fortunate because it gave me an opportunity to mould that into something that I thought was a little better. I think in those days, we often [he pauses] missed the mark. I often talk about how we try so hard when we’re making medleys to get the right combination of experimentation and expansion without going too far, and we did do that at Caber Feidh.

p|d: Went too far?

BL: I think, in retrospect, some of it was lacking a little in mature judgment, but there’s nothing wrong with that. That’s a healthy thing, and there’s not nearly enough of it now.

p|d: Are you saying that bands are more musically conservative now than they were back in the ’70s?

BL: [A thoughtful sigh] Yes. I think there’s a singular lack of imagination and energy put into constructing medleys in an interesting and attractive way, in a way that’s musically sound and still respects the basic idiom. It’s a difficult thing to do. The easiest thing is to throw a dart at somebody’s book of music until you have the requisite number of tunes to fill the five-to-seven-minute space, but it’s not a musical construction, and it’s not particularly pleasing.

p|d: Tell us about the 1979 European Championships at Shotts where, ironically, Caber Feidh might well have won had your main piobaireachd mentor, John MacFadyen, not been judging.

BL: I’m not particularly good at remembering who had us placed where and at what contests—it’s not all that important to me. I know that we played well, and I know that other judges thought we had played very well and that, with a good result from MacFadyen, we would have fared well.

MacFadyen was completely affronted and in his inimitable way wrote on the score sheet that this was a bastardization of a perfectly beautiful melody and placed us as low as he possibly could have.

John MacFadyen heard the first variation of “Macintosh’s Lament,” which we played with harmony, into “Oft In The Stilly Night” as a slow air and then into a jig. MacFadyen was completely affronted and in his inimitable way wrote on the score sheet that this was a bastardization of a perfectly beautiful melody and placed us as low as he possibly could have.

If he could have created a hole, that’s where he’d have stuck us. But in retrospect, what do you say about a thing like that? There’s a man whose devotion to piobaireachd was an all-consuming passion, and for him started to experiment with making “MacIntosh’s Lament” work as to hear our treatment of what he regarded as a sacrosanct area of the music would really have been a great insult to what he perceived to be the integrity of the music. I think he was wrong, but at the same time, I can understand how a person can do that. I recognize that there are a lot of people who, in those circumstances, just feel that something has been violated in a way that just shouldn’t be tolerated.

It’s the old objection: if you haven’t had any role in pipe bands, you really ought not to be judging them.

No one should misconstrue anything I’m saying here. John MacFadyen is instrumental in changing my piping and making me whatever piobaireachd player I am. That said, there was at the time a real question as to whether John ought to have been judging pipe bands at all. It’s the old objection: if you haven’t had any role in pipe bands, you really ought not to be judging them.

p|d: Some people might say that pipe band contests are determined these days by best sustained chanter and drone sound over closeness of playing and ensemble. What are your thoughts on this?

BL: My view is that as a practical matter in the real world, pipe band competitions are by and large tone competitions. I think that, like it or not, the band that can produce the nicest, clearest, best-sustained tone, set together which maintains good quality from start to finish is much more likely to gain a prize than one that plays more difficult music, or more expressive music, or music that is perhaps more like a good quality solo piper would play.

There is something that’s really compelling about good, bright, loud, clear tone that maintains itself. To a piper, or at least to a pipe band enthusiast, there’s almost nothing more pleasing than really finely tuned pipes played together with good presence and projection.

I think, though, that there’s more to it than that and I don’t think that sufficient credit is given for, or that people don’t listen as carefully as they might to some of the more subtle things that distinguish good playing from excellent playing. There have been performances in recent years that were played on good bagpipes with good tone and were consistent from start to finish, but were musically very ordinary and were lacking in quality and expression. Many of those performances are rewarded, and this isn’t good for piping.

p|d: Considering the work the 78th must put into the construction of medleys, and closeness of playing, do you find it exasperating or disheartening to go out and perhaps not have the most resonant tone, and lose the contest to a band that is not playing together and not expressing tunes well?

BL: First of all, I don’t think the 78th Frasers ever play, when we’re on our game, with tone that isn’t good. It is not, in my view, a volume contest, so there is never an attempt to strive solely for volume. There is always an attempt to strive for precision of tuning and sweetness of sound. When the band is playing well, there’s a quality to our sound which is more like a solo instrument magnified by twelve than anything else. It’s a tone that I would not willingly trade for many others.

It’s very disturbing to think that the degree of work and care that goes into playing the material that we play, the level of difficulty that we play at, and the fanatical devotion to precision of musical interpretation isn’t rewarded, and it’s discouraging to think that people who are judging a contest seemingly can’t hear that.

Yes, it is annoying. It’s very disturbing to think that the degree of work and care that goes into playing the material that we play, the level of difficulty that we play at, and the fanatical devotion to precision of musical interpretation isn’t rewarded, and it’s discouraging to think that people who are judging a contest seemingly can’t hear that. That is not to say that all judges are like that, because they are not. There are a significant number of judges around who do hear good playing and reward it, and take into account not just the fact that it’s difficult, but that it’s interesting, or that it’s phrased well, or that it’s played with particular musical life. The problem is that there are at least as many who never seem to hear it, and that tells me either that we’re missing the boat or that the folks listening either can’t hear it or aren’t listening for it and don’t think it’s important.

I think there has been a trend in pipe band playing for as long as I’ve been seriously around it towards simplifying and stripping the music of its gracings and embellishments. Piping isn’t anything if it isn’t gracenotes; piping is all about embellishments. The only way we can define the rhythm and the punctuation of the music is with the wonderfully complex, difficult embellishments we make. If you strip them out, you’ve taken the very guts out of piping. I just think that’s a loss to piping, and in the long run, it can do nothing but make it all ordinary and bland.

“The Mason’s Apron” medley, which sort of dragged us out of obscurity into some sort of prominence, was a product of Gerry Quigg’s imagination. He had heard a recording of an Irish group called the Boys of the Lough, and they were playing “The Mason’s Apron.” Gerry said to me, “You’ve got to hear this.”

p|d: You have always been surrounded by good—and some might say great—musical minds in your bands. I’m thinking of pipers like Gerry Quigg, John Walsh, Bruce Gandy, and Michael Grey and drummers like Reid Maxwell, Harvey Dawson and John Kerr. How much credit do you give to band members such as these for your band’s successes?

BL: A band that has been as innovative and creative as the 78th doesn’t exist by the cleverness of one person. All the people that you mentioned have had an enormous influence on what goes on in the band and in what is selected and the music that is put forward and how it is arranged. In the early days, “The Mason’s Apron” medley, which sort of dragged us out of obscurity into some sort of prominence, was a product of Gerry Quigg’s imagination. He had heard a recording of an Irish group called the Boys of the Lough, and they were playing “The Mason’s Apron.” Gerry said to me, “You’ve got to hear this. They start this thing slow and then they speed it up and they play with these bodhran things.” It was obvious that it was just a tremendous idea for a pipe band.

What do you say about John, Michael and Bruce? Look at the material that the band has played over the years. One tune after another comes from these people and great compositions. That’s part of the strength of the band. We’ve been able to attract people who have real creativity and fertile musical minds. We’ve created an environment that fosters that, I want that, I look for that, and the whole band thrives on the idea that there’s more and we can always find some fresh way to express pipe band music.

To me, however, it’s not merely the names you rightfully mention that define the quality of the band. The band has been successful because there has been a solid corps of very fine pipers and drummers who embrace the philosophy of fresh ideas, good sound, well executed technique and the commitment to producing music that is intrinsically rewarding, and not purely focused on prize winning. These people take the ideas that are presented, and they’re the ones who translate them into the finished product. Without them the band is just someone’s dream. Take away lain Symington, Tom Bowen, lain Donaldson, Bruce MacLean, Stu Liddell—the list goes on—and I’m still walking around talking about a band that would try the stuff we’ve actually done.

p|d: The 78th Frasers have lost many players since the band’s beginning, to the point that there are only two original members playing with the band right now: you and lain Symington. What’s the reason for such a high rate of turnover?

BL: The reasons range from completely ordinary and expected ones like people simply deciding that it’s time now to get on with other phases of their life. Some have left to pursue their own ambitions or pipe bands. For example, Jake Watson left to become the pipe-major of the Metro Police Pipe Band. Other people, I’m sure, find the demands to be too high: the practice schedule is rigorous, there is absolutely no sponsorship-whatever we do, we have to do completely on our own. And then there are those who feel perhaps that they don’t have the contribution that they would otherwise have in another band. I wish none of them had left.

p|d: How has the band been able to maintain a high standard when in some years four or five pipers leave, and, in one instance, a whole drum corps was basically replaced?

BL: I think that the strength of the band is a consistent musical idea, a consistent musical philosophy. The foremost requirement in the pipe corps is good piping. Everyone is encouraged to be a good piper so that you’re not just hacking away at pipe band stuff, you’re playing well, and you’re playing all the work and with all the proper expression and pointing and attention to the fine, fine detail. I think also it has to do with the desire to have a constant renewal of the music and a fresh approach to the music. If you have a consistent point of view on how you’re going to do things rather than be focused on the prize, then I think you’re going to attract people who share that view, who want to be good, who want to play well, who want to participate in something that goes forward in an innovative way.

p|d: Other than your own, what pipe band is your favourite just now?

BL: Strathclyde Police. They’re a stunning band when they’re on their game. They play with wonderful tone, but they play with a lot more than that. I think that to hear the Strathclyde Police under full sail in a March, Strathspey and Reel is a tremendous experience: musical, thoughtful, full of work, full of execution, full of expression. I don’t know that there’s anybody else quite like them.

p|d: They’re certainly not a band very similar to your own.

BL: Oh, no, we’re almost diametrically opposed in many ways.

p|d: Do you think there’s a band similar to the 78th?

BL: I don’t really know that there is one that over the course of thirteen or fourteen years has made the bringing of fresh music to pipe bands a major objective or goal. Some of them have toyed with the idea of it and have backed away from it and I get the sense that some bands want to do that because they hear the fun that there is in playing that kind of music and they hear that it sometimes can win a World’s Championship if it is played well, but I don’t think that anybody else has committed to it in the way the 78th is.

In terms of my leadership style, whoever says that I’m a crack-the-whip pipe major is obviously dreaming.

p|d: As a pipe major, how would you describe yourself?

BL: It’s difficult to describe one’s self and not sound immodest, but what characterizes my leadership is a commitment to trying to make really fine music. In terms of my leadership style, whoever says that I’m a crack-the-whip pipe major is obviously dreaming.

This is not a bloody football team. You can’t go out and play good music by butting heads like a linesman in the NFL. You’ve got to encourage people to play music. It’s art, and you can’t scream and yell and hope that by fear they’re going to play the third part of

“Lochaber Gathering” with beautiful expression. I think I’m only ever harsh when the band is letting itself down and letting me down. I find that I’m only ever crabby about things when people don’t make a reasonable effort. That’s all you can expect of people, to do the very best that they can. If they do, that’s it, there can’t be any more that you can ask of them. Screaming and yelling and laying down the law and intimidating isn’t going to accomplish anything, and on top of that, it’s simply not my style. I just couldn’t do it. People would laugh at me if I tried.

p|d: What are the key ingredients that make a great pipe band?

BL: I think that what distinguishes good pipe bands from great pipe bands is that singular devotion to some kind of ideal. If you think of bands over the past few years that you would perhaps think of as great, you’ll always find something that comes immediately to the front of your mind about them. If you think about the Shotts band in the glory years, it’s very clear what they were about with the great huge tone and volume and Alex Duthart’s accompaniment. Think of Muirhead & Sons when it was rolling: the precision, the care and great attention to detail, probably more like the Frasers than any other band I can think of-I’m flattering us by saying that. The Glasgow/Strathclyde Police we’ve already talked about: there’s just a wonderful, musical forward motion in their playing, particularly in their March, Strathspey and Reel playing.

The Edinburgh Police, when they were still the Edinburgh Police under lain McLeod, The sweetness of tone and imaginative construction and playing of medleys: using light jigs, strathspeys and reels when it was a completely new format. You can hear in your mind what all those bands are about, and that’s what makes a band great as opposed to good. Winning the World’s Championship alone doesn’t make you a great band. It just makes you a good prize winning band at the end of the day.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of Bill Livingstone: the pipes|druims Interview from the Archives coming soon.

NO COMMENTS YET