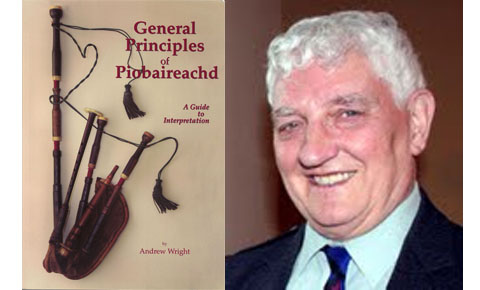

Andrew Wright: the 1995 pipes|drums Interview – Part 2

We continue our December 1994 exclusive pipes|drums Interview with the late great piper Andrew Wright.

In Part 1, he discussed his piping roots and his work as a piper in the famous Grade 1 Red Hackle Pipe Band under Pipe-Major John Weatherston. Combined with his solo piping prowess, his pipe band work led to a long career as a judge with the RSPBA, where he gained a reputation for occasionally bold calls, never afraid to judge a contest exactly as he heard it.

In Part 2, Andrew Wright goes into what he was most known for: piobaireachd. While he is perhaps most associated with Robert Brown and Robert Nicol as a student of the teaching of The Bobs of Balmoral, he actually studied for more with the great Donald MacLeod. Some would say that Wright was MacLeod’s greatest pupil, if greatness were decided by the amount he passed along MacLeod’s knowledge.

As a master with a vast knowledge of piobaireachd, one might be surprised by Wright’s choices as the greatest pieces ever made, as well as the tunes, at least in 1994, that he most enjoyed playing.

It’s another fascinating snapshot in time with one of the most fascinating exponents of the art of Highland piping.

Part 2

pipes|drums: Let’s switch gears now to piobaireachd. The Clasp has eluded you so far, but you’re still considered to be one of the most musical and knowledgeable piobaireachd players in the world. Do you see not winning the Clasp as a hole in your career that needs to be filled?

Andrew Wright: My interest in piobaireachd has mainly been on the subject as a whole rather than to win prizes. I’ve had a share of the prizes and I’ve been thrilled by the awards when they’ve come. I do not now attach a great deal of significance to prizes. I still compete and intend to do so for a number of years yet. John MacDonald of Inverness won a Clasp when he was in his seventies. I just enjoy playing.

p|d: You know hundreds of piobaireachds and settings of tunes. What one tune, and one tune only, do you personally think is the best ever composed and why?

AW: The greatest piobaireachds are generally accepted as being the three great laments: “The Children,” “Patrick Og,” and “Donald Ban,” and they are of course MacCrimmon compositions. Perhaps romanticism over the years has played a part in that assessment. If we consider only MacCrimmon tunes I would certainly place “Lament for the Earl of Antrim” in there at the expense of one of the others.

I often think the greatest composition is out-with this group: “MacDougall’s Gathering,” whilst not falling within the generally accepted forms of construction, has many attributes which the other tunes don’t have.

But I often think the greatest composition is out-with this group: “MacDougall’s Gathering,” whilst not falling within the generally accepted forms of construction, has many attributes which the other tunes don’t have. It has every expressive device that a piobaireachd player could wish for: the descending, harmonic intervals in the first three bars of the third line make it, for me, one of the most enjoyable passages to play in piobaireachd and show off to great effect the beauty of the pipe scale. The device of switching the accents in the third line of the Taorluath and Crunluath doubling is not to be found in any other piobaireachd and this makes the piece masterful and unique.

The title of the tune comes only from the name added by an unknown hand to the manuscript of Angus MacArthur where it had been one of the nameless tunes. It is of great wonderment to me how a piece of music such as this, and which in all probability could be only 200 years old, can come down, and we do not know where it came from. I often wonder just how much has been lost in piobaireachd.

p|d: What are your favourite piobaireachds to play?

AW: What my favourite tune to play has altered over the years. A large number of them have been my favourite at one time or another, so I don’t really have a favourite, but if pushed I would say “The Earl of Seaforth’s Salute,” “Lament for Donald Duaghal MacKay,” and “The Lament for Mary MacLeod.”

My liberal approach is more likely to apply to judging. Anything I’ve taught is based on what I got from them, although I would like to think there’s a little bit of Andrew Wright lurking in there somewhere.

p|d: In your piobaireachd instruction you are considerate of other interpretations, which is odd considering that Bob Nicol, by most accounts, had a strict allegiance to John MacDonald’s teaching. Is your liberal approach a result of being taught by several authorities, that is, Donald MacLeod, Bob Brown and Bob Nicol?

AW: Anything that I teach is based on what I learned from these three men who were all taught by John MacDonald. If there is any liberalism in my instruction it’s probably geared more toward settings of tunes rather than style of play. These men all played with the same approach to phrasing, and they all shaped the phrases the same way. No two people can play with the exact same timing, and it would have been impossible to have become a replica of any of them.

My liberal approach is more likely to apply to judging. Anything I’ve taught is based on what I got from them, although I would like to think there’s a little bit of Andrew Wright lurking in there somewhere.

p|d: What about the Coeur d’Alene piping school? You’ve been an instructor there for about twenty years now.

AW: I first went there with Bob Hardie in 1972, and I’ve been back every other year since. I’ve been with the late John Wilson of Canada; James Campbell, Kilberry; Donald Morrison; Jimmy MacGregor; Evan McRae; Bob Wallace, as well as Canadian instructors like Jamie Troy, Hal Senyk and Bruce Gandy. It’s a very large school, with often over a hundred students. I’m always amazed at the great interest in piobaireachd North Americans have. They have a far greater interest in America than that in Scotland. Scots look at piobaireachd as a competition event, where more North Americans look at it as a subject in itself that should be studied. In Scotland, it is viewed as something that a top class player plays, whereas in America there are people of all levels who want to learn about it, who want to learn how to play it. I find that very gratifying.

Too much can be made of the so- called Cameron and MacPherson styles. The important thing is that the player adheres to a pattern-whatever that pattern is-and to do that he must of course first have seen the pattern.

p|d: Have you ever played a piobaireachd in another style to improve your chances of winning the contest?

AW: I’ve never gone for a prize like that. I would never play any other way than what I consider to make musical common sense. The prize to me would never become that important.

Too much can be made of the so- called Cameron and MacPherson styles. The important thing is that the player adheres to a pattern-whatever that pattern is-and to do that he must of course first have seen the pattern.

The difference in these styles, as far as I can see, can be related to patterns of speech, that is, one person speaking two or three words at a time as against another person who speaks a whole sentence at a time. In piobaireachd these divisions are decided entirely by the length of certain notes. Stylistic differences only really apply when we go back to the early manuscripts. What is shown there differs wildly from what is played today. I think people make too much of the Cameron and MacPherson styles. I think pipers like to have a hallmark. If they say they play the MacPherson style or the Cameron style they think it gives what they play credibility, and the reverse is also often the case.

p|d: Peter MacLeod Sr. was a fascinating character in piping history, although not too much has been written about him. You had much of your early instruction from Peter MacLeod. Can you tell us a little about him?

AW: Peter R. MacLeod was my first formal instructor. He was a pipe-major in the Cameronian Scottish Rifles during the First World War. Afterwards he worked as a shipwright of the shipyard D&W Henderson in Glasgow where he lost a leg in an accident on a winch. His artificial limb gave him problems for many years and I remember him often having to get up and walk around the room rather than sit, so as to ease the pain. He died in Erskine Hospital outside Glasgow in 1961.

He was well on in years when I first went to him in Partick, Glasgow. He played in a round, fast, and open style. He introduced me to piobaireachd and the first tune I got from him was “The Lament for the Only Son,” which, in retrospect, seems quite a heavy task for a beginner. He had the reputation for being hard to get on with, but I never found him to be so. He had definite views about anything to do with the music. He originated from Stornoway on Lewis, and the titles of many of his large number of tunes relate to that area. His fame is as a composer, and his huge output of tunes are, on the whole, very technical in their content whilst being highly original in melody.

p|d: Did you ever know his son, Peter Jr.?

AW: Peter Jr., was also a prolific composer and a brilliant player, especially of light music. As a young boy I got to know him very well when he returned from South Africa in the late 1950s. He had been absent from the competing stage for a large number of years, but he came right back and took prizes against players like Donald MacLeod and John MacLellan in their prime. He had absolutely acrobatic fingers. Donald MacLean of Oban had told me some years previously that the only weakness he had was his birl, but I never noticed anything weak about his birl.

Perhaps looking back he gave the impression of arrogance. I remember him competing with marches such as “Colonel Stockwell” and William Ferguson’s “Duchess of Montrose.” He played in a very clipped and pointed style, much different from his father.

p|d: Both Peter MacLeods were composers, so did you ever have a chance to hear their tunes before anyone else?

AW: Peter Sr.’s output had probably slowed down by the time I got to know him, but Peter Jr. taught me on the fingers various tunes that he had recently come up with or he had taken home from South Africa. One particular tune I remember well was a slow air called “Bertie Gas,” which he called after a South African vagabond. Peter Sr. composed a piobaireachd, “Salute to Dame Flora MacLeod of MacLeod,” which stands up very well against many of the ancient compositions.

Many of their tunes were joint compositions. One tune that comes to mind is the excellent reel, “Amish Light,” where the first two parts were composed by Peter Jr. and the second two parts by Peter Sr. Incidentally, there are still a large number of excellent tunes that are unpublished.

p|d: By Peter Sr. or Jr.?

AW: Both. One in particular must be of the best slow airs that Peter Sr. composed, which he named “Alice Cunningham,” after his wife. I know of a two terrific 6/8 marches composed by Peter Jr., a couple of waltzes, and numerous jigs.

Some of Peter Sr.’s tunes tend to have more than one name because he quite easily fell out with people. If he composed a tune for somebody and then fell out with them he’d change the name.

p|d: Peter Jr. died young, didn’t he?

AW: Yes, he died in 1977.

p|d: What tune did Peter MacLeod Sr. believe to be his best composition?

AW: It often puzzled him why some of his compositions were not played or did not catch on as well as other tunes that he considered less good. The march, “Murdo MacLeod,” and the jig, “Patrick Og,” come to mind. He was particularly proud of the great reel, “John Morrison of Assynt House.”

p|d: What about Donald MacLeod? How long and frequently did you go to Donald MacLeod for lessons?

AW: Donald came to Glasgow in 1963, and I went to him from then on a regular basis. That was once a week for about six months per year until 1972 or ’73 and thereafter I went intermittently until he died in 1982, so I was always in close touch with him. I was very fortunate because Donald stayed in Cardonald, which is in one side of the Glasgow/Paisley, boundary and I stayed right on the other side of the Glasgow/Paisley boundary. I could walk to Donald’s in half an hour.

Donald MacLeod had total recall of any tune that we ever discussed, and much of his teaching method was based on playing the tune through together on the chanter, he led and I followed. When he played piobaireachd, there was never any searching for the length of a note, everything he did was very concise and definite and he could hit his timing without fail whatever the occasion.

p|d: What are some of your stand-out memories of Donald MacLeod?

AW: I had about six piobaireachds when I first went to him, and the first tune he ever put me onto was “Lament for Captain MacDougall,” which has always been one of my favourites. I found his style of playing very fast compared with what I had been doing before. He spent much time getting me to keep things moving. Donald played the tunes faster than most players. We used to go over the set tunes for the Medal every year, plus many others.

Donald MacLeod had total recall of any tune that we ever discussed, and much of his teaching method was based on playing the tune through together on the chanter, he led and I followed. When he played piobaireachd, there was never any searching for the length of a note, everything he did was very concise and definite and he could hit his timing without fail whatever the occasion. He did a bit of singing in lessons, but most of his teaching was through directing by example on the chanter. His manner at all times was completely courteous; he had tremendous patience.

The first time I ever heard him play was in one of the Scottish Pipers professional competitions in the old Highland Institute on Elmbank Street in Glasgow. I sat there listening to all the piobaireachds and when Donald came on I was immediately taken by the quietness of his pipe, and his neatness. He was not tall, and in these days he was very thin. I can remember him well with the army battle dress, glengarry and the Seaforth kilt, and compared with other bagpipes, his instrument was sweet and very quiet. He won the competition playing “The Blind Piper’s Obstinacy,” and that was the first tune I ever heard him play. That would be in the mid-1950s.

p|d: What was his approach to teaching piobaireachd? Would he talk a lot about his teacher, John MacDonald, like, say, Brown and Nicol would? How does that relate to your own style of teaching?

AW: He sometimes used to talk about MacDonald being cutting. Donald often related about how after he won the Gold Medal playing “Glengarry’s March.” MacDonald the next time wanted to hear him playing “Glengarry’s March.” He played it for him and MacDonald said, “They never gave you a Gold Medal for that did they?” So that was MacDonald’s style. But it certainly wasn’t Donald’s style of teaching. Donald was courteous and encouraging. My own style of teaching is just how I’ve fallen into it. One learns how to communicate with people and when I teach I try to be analytical.

p|d: What caused you to seek instruction from Brown and Nicol?

AW: In 1968 I was the secretary of the Scottish Pipers Association in Glasgow. The president at that time was John MacFadyen, and he arranged for R.U. Brown to do a two week course in Glasgow. It was held in the RSPBA headquarters, and as secretary I got the job of looking after Bob Brown and transporting him to and from the venue. He taught all day and most evenings. Donald MacLeod insisted that I go, and I took a lot of time off work. A lot of the tunes that he went over I had already done with Donald.

p|d: Did you notice much difference?

AW: The tinting was practically the same, but Brown tended to linger more on the pulse note and his presentation was slower. He did all of his teaching by singing and extracted expression from every note. Like Donald, he had total recall and never referred to a book unless to point out something. He gifted me a complete set of recordings on the pipes of about 70 or 80 tunes, and I have spent a lot of time studying these tapes over the years.

p|d: Then you eventually made the long trip from Paisley to Balmoral for further tuition.

AW: I got to know Nicol about 1971 after I competed at Braemar games. He sought roe out after the competition to point out one or two things in my timing. Both Brown and Nicol did this after every competition they judged-they made a point of being available for discussion after the result came out and not always to give praise. He gave me an open invitation to visit him and the following year when I was working in the Aberdeen area I paid him a visit where he stayed at Birkhall, Ballater, and thereafter I went about once every two months until he died in 1978. Leaving Paisley early on a Sunday morning, I met him when he came out of church, played for him all afternoon and drove home in the evening.

His approach was much more forceful than Brown’s, and he gave the impression of being gruff, and unapproachable. This was only a front He was very kind and had a unique sense of humour.

His timing was not exactly the same as Brown’s in some parts of some tunes, but he always insisted that what he gave me was exactly as he got it from John MacDonald. The first tune he ever put roe through was the “Lament for Donald Duaghal MacKay.” I have him singing it and many other tunes because I used to record every lesson with him. The recording I have of him singing “Donald Duaghal”, he starts off by saying, ”This is how old Johnny gave it to me.” He always made a point of saying that. He was also an excellent reedmaker, his chanter reeds fitting to perfection the Hardie chanter. He made terrific reeds, but in limited numbers.

p|d: Considering Nicol’s reputation as being unflinching in allegiance to John MacDonald, do you think he did some damage to piobaireachd in addition to his great contributions?

AW: He always considered himself privileged and fortunate to have come under MacDonald’s wing, he and Brown being sent there by the late King. He told me that MacDonald would give him and Brown different tunes, maybe three or four tunes at a time. They would take them away, and then they had to teach the tunes to each other and come back and play the total number of tunes. All the teaching was done by singing. I often think that because the Bobs stayed near each other in a part of rural Scotland, being steeped in the music for many years together, might have inadvertently developed MacDonald’s teaching further. Perhaps this is why Nicol was always insistent on going back to first principles. His approach would have been one of preservation. John MacDonald made a number of recordings on the old 78 rpm gramophone discs, and I had some of these transcribed onto a cassette. The playing is beautiful on an old low pitched bagpipe with the high A disappearing into the drones. I listen to this often and I would say that Nicol’s playing is closer to MacDonald’s than the others.

p|d: You mean compared with Brown and Donald MacLeod?

AW: Yes, Brown was slowish and very, very, expressive. Nicol had a more robust and round style, while Donald was more staccato.

p|d: Who was the smarter piobaireachd player?

AW: I wouldn’t want to make a choice, but Brown could have given the best piobaireachd performance I ever heard, but I never heard Nicol in his prime. It’s only my opinion. I think Brown tackled tunes in one of a number of set ways. He didn’t differentiate much between his approach to a lament or a salute or a gathering. Nicol would certainly be faster paced and so would Donald. If it was a salute they would go fairly quickly at it. I think Brown just went with the notes in the tune.

p|d: In 1987 you undertook on behalf of the John MacFadyen Memorial Trust to transcribe the MacArthur Manuscript, but it hasn’t appeared yet. What’s happened to that project?

AW: At one of the MacFadyen seminars in Skye the manuscript was discussed, and the idea came up that it would be good to have it published. I undertook the transcription purely as an academic exercise, and I worked on it during the winter of 1987-88. It has been completed, but I don’t think the Trust fund had the money to publish it. My understanding is that they’ve got the money now, but they think it should take a form different to the way I transcribed it. In fact, the original MacArthur Manuscript is full of mistakes. The writer was searching how to present the music, and there are bars where he has written the gracings one way, and when the bar’s repeated he writes the gracings another way. Some note groups are unplayable as written.

It’s very interesting. There are different settings of tunes, completely different timings, and completely different gracenote systems, so there could be an element of wanting to leave well enough alone and play what we have.

The actual transcription was fairly easy, but the point of doubt would be in the editing. The view now seems to be that it shouldn’t have been edited, that we just put it in, warts and all. When I started off, the intention was to publish the edited page alongside the original page. That could be holding things up, but it’s in the hands of a committee now. It’s a classic case of the goalposts moving.

p|d: Well, we hope to see it sometime in the future.

AW: It could be something the Piobaireachd Society eventually takes on.

p|d: Do you have any plans to put your knowledge of ceol mor — the music, the personalities, the history, everything that you’ve done within your life — into a book, maybe an autobiography?

AW: The thought has taken me from time to time; perhaps when I stop playing and practicing more time will become available. I often think that there is a need for a modern day treatise on the subject of piobaireachd as a whole, something that covered, say, history, analysis of styles of play, classification of tunes by playing method rather than by structure, lore and information on playing styles. Such a project would no doubt be met with skepticism by piobaireachd players and enthusiasts, as experience has shown me that people are reluctant to consider what they have never been taught or encountered before. In fact, pipers are inclined to hide within the realms of oral tradition, which is wholly dependent upon the integrity and intellect of those passing the message on.

Stay tuned for the next in our nearly 40 years of pipes|drums Interviews. If you enjoyed this and all the other free content, please consider becoming a subscriber. A whole year of pipes|drums costs less than the next round at the pub. All revenues are plowed back into the publication. Anything left over is donated to worth nonprofit piping and drumming causes. (If you subscribe, thank you!)

And another reminder that all content published by GHB Communications in print or online is copyright and may not be reproduced in any manner without expressed written consent.

NO COMMENTS YET