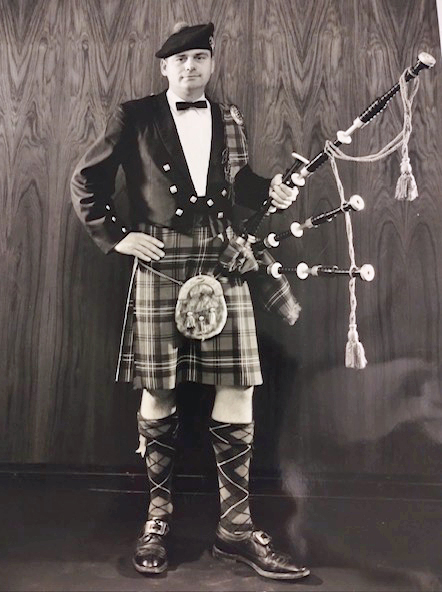

Roger Ritchie: an interview with the 90-year-old 78-year member of Connecticut’s Manchester Pipe Band

Roger Ritchie might hold the all-time world record for longest tenure with a competing pipe band.

The 90-year-old Connecticut native has been a member of the Manchester Pipe Band for 78 years and counting. Ritchie is a legend with players all over the northeastern United States and beyond. His son, Donald, is also an accomplished piper and a past Manchester and Massachusett’s Worcester Kilite member.

The Manchester Pipe Band has great longevity, this year marking 110 years since it was founded. It is consistently one of the eastern United States’ best competing bands, featuring a host of accomplished pipers and drummers.

While more pipers and drummers today are actively competing into their fifties, sixties and seventies, Roger Ritchie is perhaps something of a trendsetter.

We were delighted when Roger Ritchie’s friend and former bandmate Don Dixon contacted us with an interview he conducted with Ritchie. Dixon himself was a piper with Manchester for some 42 years before joining the Glengarry Pipe Band in Ontario.

The conversation covers Roger Ritchie’s piping longevity, his years of membership with Manchester, and the myriad changes he’s seen in piping and drumming over his 90 years.

Don Dixon: How many years with the Manchester Pipe Band, Roger?

Roger Ritchie: Total? Let’s just call it over 70 years.

DD: How did you get started with piping? Was there a family connection?

RR: Yes, there was a family connection. My older brother had become quite a good piper. Then, he went into the navy. I got started on the pipes in 1945 or 1946. My father, William Ritchie, played pipes and was also a drummer, actually, the drum sergeant of the band at that time. At that time, Pipe-Major John Stevenson was running a group for beginners on Friday nights. We would get together in the upstairs of the Washington Social Club. The pipe-major would come around and listen to each player. The first pipes I attempted to play are the pipes you [Don Dixon] have now. In fact, I think they had the original bag! [These are pre-1900 Hendersons). My brother played those same pipes when he started out. I think he started in 1938. He was about 12 or 13 when he started. In the 1941 group picture of the band, he looks as tall as the men in the band. That’s because he’s standing on a pipe box!

DD: How did your father get into piping?

RR: Well, He came to this country in 1923. He had heard pipe bands in Ireland and Scotland; he was born in Scotland and always liked the sound. He had played in flute bands in Northern Ireland. At that time, the Orange Lodge in Manchester had a very good flute band. He played with them as a drummer for quite a while. Then, he found out that the other Orange Lodge in Manchester had a pipe band that was reforming. The Manchester Pipe Band started in 1914. He decided to learn the pipes. He was in his twenties. He was a natural musician who could get a tune out of anything: a trumpet, a mouth harp, a violin.

Then, I came along. He never pressured me and didn’t tell me if I was any good. Sometimes, he’d give me hell if I was playing too fast! That’s not a problem anymore [Roger chuckles). The band had a pretty good repertoire for a street band. I had gotten a few tunes off and the next thing I knew, I had a uniform. This was my introduction to the parade element. This was 1946. The first parade I played in was in Danielson, CT., and it was a VJ Day parade. [Victory over Japan). There was all that stuff going on, everybody was happy again!

I was pretty much a parade piper at this time- I was not ready for competition. But, at this time, the band would compete at Schenectady, New York [now the Altamont Games). It was at a place called Locomotive Park right in Schenectady itself, in a park owned by a company that built locomotives and army tanks. All of the bands would meet downtown at the Scottish Club and parade up the Main Street to drum up interest for the games. Then, the bands would pack up and go off to the field and have a good time. We were competitive with the other bands, never won, I don’t think but always seemed to get a prize. We were in the same class as the Worcester Kilties at that time.

Don: Do you remember some of the other bands at that time?

RR: Yes. There was a pretty good band from Yonkers; the Boston Caledonians were playing well at that time. Clan Sutherland was good. and another Boston band. They all played well, better than us. I think I started playing in contests after about four or five years, around 1950. I finally got all the tunes off.

We were pretty much a sharp-looking parade band. The highlight of my younger days was going to Atlantic City to play in the Tall Cedars annual convention parade. We had twelve pipers and about 8 or 9 drummers. They took a photo of us coming by the reviewing stand, which was about the nicest picture you would ever see of a pipe band. Everybody was in step and lined up. I’m the only one left of that group. Then, it was back to the everyday parades, which didn’t compare. Atlantic City was the place to be back then. Had a good time. My father didn’t know where I was half of the time.

I look back on that now, I probably should not have been part of that group. Most of them had served in the war, their language was rough. The behaviour wasn’t what I should have been hearing or seeing. But I got my nose right into it.

After the parade, we were on the boardwalk. A fellow who knew me and the family was determined to get me up on this stage to play at the convention concert in Convention Hall. I was in uniform but didn’t have my pipes with me. I was about 13 or 14 at the time. I asked one of the drummers to get on stage with me. I played pretty good. I got a rousing ovation. It was the highlight of my life up to that point! Getting there, we drove right through the battery, Lincoln Tunnel and all that stuff. I’d never seen any of that before. By Grant’s Tomb, right through the city.

I look back on that now, I probably should not have been part of that group. Most of them had served in the war, their language was rough. The behaviour wasn’t what I should have been hearing or seeing. But I got my nose right into it. Sometimes, my older brother would come out of nowhere and grab me by the neck to get me out of there. He was seven years older. Sometimes, they’d be showing me pictures I shouldn’t see. And again, my brother would come out mad and drag me away. It was educational!

The band always had an annual banquet and election of officers. Always went somewhere for a meal. When it was time for entertainment, we had five or six guys who could get up and sing. The other guys would get up and tell dirty jokes. So, when the singing stopped, us young guys had to leave the room.

We had to stand outside with a chaperone.

DD: Roger, I hate to interrupt, but in my days with the American Scottish Pipe Band in Syracuse, we had two or three Scottish members. When we had a band function, they would get up and start singing songs like “A Wee Deoch Doris” or “I Belong to Glasgow.”

RR: Harry Fellow, our bass drummer at the time, was a Glasgow guy. We had an Irishman named Billy Hall. He sang “Paddy McGinty’s Goat.” Ray Gordon, another Irishman, sang a song called “Hello Patsy Fagan.” My brother Bill always sang a song called “Slattery’s Mounted Foot.” We were never starved for entertainment!

DD: Was your father your first teacher?

RR: No. I started drumming lessons first. When I got interested in pipes, that was the end of my drumming career. I played the pipes that Dixon has now. My father used to have a Belfast paper sent to him. One day he spotted an ad “Bagpipes for Sale” – $75. He got a check off right away. They arrived, and my brother got them going. I’ve been playing them ever since. [Roger is thinking hard for the name of the pipes) Hendersons employed them, and one of them was an expert wood turner. The other had some business acumen. But they only lasted about 2 ½ years. One got sick. They are pretty hard to find, but, they are identical to Hendersons. They took everything with them when they left Hendersons. For $75, you couldn’t go wrong. [Roger couldn’t remember what make his pipes were at the time, but he has since remembered, they were Williamson and Jeffrey pipes!) He still plays them to this day.

DD: Talk a little bit about how bands like Worcester and Manchester filled their ranks with people from Scotland.

RR: Well, we found out what Worcester was doing by accident. The Manchester band used to run things out of the Orange Hall. Every so often, they would have “Pipe Band Night,” where they would invite all of the bands around to come and have a good time. We had the Boston Caledonians, Worcester, and St. Patrick’s. My friend, Gordon McGowan, who was a Scotsman playing in the Manchester band at the time, got acquainted with the one and only James Kerr, heard him play and was very impressed. He told Gordon that he was an importee come over to play in the band. Worcester did pretty well doing that for a while. But then some of the wives got homesick and they lost some of the players who were “poached” from them to go to other bands. Some of the imported guys were having hard times with employment, so they were vulnerable, so other bands found their jobs, and away they went. Jimmy Rankin had been pipe-major of the band for a while, away he went to Bridgeport.

They lost quite a few guys. They were facing a lean year, having lost members of the pipe corps. Their leading drummer, Alex Coville, had returned to Scotland. The only guys they had then were two of the old, old Worcester drummers. But these drummers carried them through until they got some great drummers. One time those two old guys actually won the drumming, just the two of them. So, when Gordon McGowan went to play with Worcester. Now, they had enough pipers, nine or 10, but they started importing again, very actively. After Roger went to Worcester, Willie Bald, Bob Burnet, Neil Gow, Tom Sherer, Bill Cowan, former pipe-sergeant of Renfrew, George McKendrick, Glasgow Police, friends with the Kerrs, Rab Kerr, James’s father, taught George to play.

We were knocking off everybody. Everybody loved us, we had a good sound. We had people who knew how to tune pipes. The pipers that we had didn’t need a lot of advice on how to play things. They all came from good bands. It didn’t take them long to pick up how to play the Worcester way.

Worcester really started getting better. In those days, a Grade 1 band had to submit three MSRs. Medleys hadn’t been introduced yet. So, we [Worcester) were knocking off everybody. Everybody loved us, we had a good sound. We had people who knew how to tune pipes. The pipers that we had didn’t need a lot of advice on how to play things. They all came from good bands. It didn’t take them long to pick up how to play the Worcester way.

So, then they started talking about going to Scotland. We went to Scotland with 15 pipers and four or five sides, and we did pretty well. The first contest was Markinch; we got a prize there. At the World’s in Glasgow, I think we came in fourth or fifth out of some of the best Grade 1 bands. We were treated quite well by the Scottish bands. We got together with Shotts and Dykehead after one of the contests and had a good time—we drowned our sorrows!

The band had ordered a bunch of new chanters from Hardie. Hardie was very busy, everybody wanted a Hardie chanter at the time. I was staying near Hardie’s shop. So, they sent me to Hardie’s shop to see how our order was coming. There were chanters everywhere. He was aware of our order. He said he would bring them with him [Hardie was pipe-major of Muirhead and Sons at the time]. His partner, John Winston, showed up at the Worlds with a paper bag full of chanters. I found James Kerr and gave each piper in the band a chanter. He told them to put them in their pipe cases so they wouldn’t have to pay any dues. So, we saved a few bucks. We played those for a long time.

DD: So, how long have you been with Worcester?

RR: Well, I had two careers. Donnie [his son] came along. I was there for around seven years in total.

DD: And what was going on with Manchester at that time?

RR: Not too much. We went through a lot of pipe-majors. Chuck [Murdoch] would have been the obvious choice, but he was working for Pratt & Whitney up in Montreal, so he wasn’t available. He was the pipe-sergeant, however. Other people tried, including myself. Chuck was committed to playing with Worcester. He played at the World’s with them and stayed on for a year. Then, he took over the Manchester band around 1967.

He didn’t have much to work with at the time. The band was very low on money. Chuck had picked up a lot of knowledge during the time he was with Worcester. He was very observant. He was watching [James] Kerr do his magic. He became very good at tuning himself. He had a great ear. Even Kerr said he taught him too much. Chuck was a natural gatherer of information. He would just store it away. Every time he adjusted my reed, it always sounded better. I don’t know what the hell he did.

Then, we tried importing players with some success. But most of them didn’t want to stay around Manchester. Too dull! They were free to do as they pleased. There was no obligation. At that time, bringing people over was much more difficult than it had been before. You had to be sure they were not displacing someone else employment-wise. Had to have a written guarantee that they would have employment when they got here. It used to be much easier. Sign a few people and they’d be on the next boat. That’s how my parents got here. You never see a Scottish immigrant anymore.

DD: When you brought people over, did you try to get them employment?

Any drummer who came to Manchester hoping to play with that drum corps found it difficult to learn the scores. They could take a recording, but there was no written music.

RR: Oh, you had to guarantee that they had a job, were machinists, and were labourers. They were all tradesmen. But then we started losing them, too. Guys either moved to another part of the country or went back to Scotland.

Chuck and Gordon McGowan decided the band would go with teaching kids instead. Drew Nisbett built a drum corps from nothing, including himself, Mike St. Germain, Scott Yeomans, and his son John. Drew trained them all from scratch. He could get them to do what he wanted; they never saw a sheet of music. But any drummer who came to Manchester hoping to play with that drum corps found it difficult to learn the scores. They could take a recording, but there was no written music.

We were pretty successful with the youth movement. There are a lot of kids in some of the old pictures: Ian Beatty, Willie Mathieson, Don Ritchie, Brendan Cunningham and others.

We started being pretty competitive, and we would go any place where there was a contest.

The band started drawing people from other areas [Dixon and his wife, Kate, a piper, were perfect examples of that, having moved from Central New York to play with the band.] We were winning. Nobody wants to be standing out in the field with their drawers hanging down, watching the winners march off!

We’d be in the beer tent before they left the field. So, we were very successful. We won Grade 2 two years in a row at Cambridge, Ontario. Never did that great at Maxville, kind of a letdown.

DD: I remember the first year we went to Cambridge, we had 8 pipers. Brian [Green] was pipe-major. Brian had a bag blowout and had to fake playing through the whole MSR. Roger had a buddy in the Dofasco band who he was talking to in massed bands before awards were handed out. He told Roger no way Manchester could win because we only had 8 pipers. He didn’t know that there only 7 really playing. But we were announced as winners and we got to march off the field right behind the 78th!! That was such a thrill for me.

RR: The first year we went to Cambridge, we hadn’t won anywhere, but we got first at Cambridge!

We went to another contest in Ontario, which only lasted one or two years. We were Grade 2 at the time. We played in the Open Slow March and 6/8 contest, and we won against the Grade 1 bands. Chuck picked Loch Rannoch because he knew John Wilson [who wrote that tune], was going to be judging and Wilson loved it. He never put his pencil on the paper. We played it the way he liked it. Chuck knew how to play the game! He never bragged. Everybody liked him.

DD: In those days, a band contest was pretty much an MSR and a slow march, correct?

RR: That’s right. Sometimes, you had to break into a 6/8 after the slow march. There wasn’t a lot of money to win then.

Thousand Islands had a contest for a while that didn’t last too long.

DD: Any good pipe band character stories?

RR: Nate Shepherd. He was something else and had a fixation with guns. He went into the Orange Hall Social Club to have a beer with some of the band after practice. He had a 45 pistol fall out of his coat onto the floor. That caused quite a commotion in the club. No one knew he was armed. Another time, he had bought a gun and was eager to test it. So, he made himself a little shooting gallery in his apartment and he fired a round in his apartment. Turns out the gun was a lot stronger than he thought, and damned if it didn’t hit his pipe bag and kept on going. He was supposedly an ex-marine. Don’t know whatever happened to him. He struggled to play in the band. He and Greg King were friends in the band. Those guys struggled, yet the band sounded good when competing.

Jim Stroh and Janet Cassidy were a couple who came along. They struggled to play in the competition group but still enjoyed parades and such.

Joann Scott came along and played in the Grade 4 band. At one point, Manchester had bands in Grades 2, 4 and 5. That was the most prosperous time for the band. We had so many kids playing in the band, mostly taught by Chuck Murdoch. That level of teaching has been missed. When the band started practicing on Thursday nights, we kept the hall on Mondays for teaching pupils, including Ian Dixon, Eric Ouelette, and Jed and Jared Otto. Willie Mathieson was one of Chuck Murdoch’s first successful students with solos. He would enter contests and come looking for me to borrow my pipes because my pipes were going well and he couldn’t be bothered with getting his own pipes going. He knew he could come to me and he did very well. His grandfather brought him down faithfully. His grandfather was a former pipe-major of the Holyoke Band. His name was Wilson Mathieson. The family used to follow the band around.

DD: What was the best period for the Manchester band?

RR: It was probably the early 2000s. Chuck had students like Eric Ouelette, Ian Dixon, and the Ottos. Ian Beatty was a good young player just before this time. Also, many out-of-state pipers were attracted: June Hanley, Nancy Tunnicliffe, the McGonigals, Brian Green, and Mike MacNinch. Yes, we were rolling then.

We also had Jeff Otto as band president. He was always finding all kinds of jobs for us, even in the middle of winter with effing snow on the ground, colder than hell. He was a very good president. He ran the band well. He was very dedicated. He would also listen to all the complaints of people in the band, there was always a line to talk to him.

DD: The band was really doing well. We had just gotten all new uniforms from Geoffrey the Tailor; we looked good and sounded very good. We were following the SFU model of putting all the bands out there that we could and it was working well. Kids moving up the grades, all taught by Chuck. The kids would get comments on their scoresheets like “Very well taught,” “Good fundamentals,” etc. It was a lot of fun having the kids in the band, very exciting. The kids would compete solos and would attract other good players.

RR: When Chuck Murdoch stepped down as pipe-major, we lost a lot of talent. People went back to their local bands, etc. So, when Brian Green took over, he had to build it back up.

DD: Other characters? Walter Wilkie played with Manchester, right? He came to my band in Syracuse for a very short time.

RR: Yes. He was from the Scots Guards. He actually had a photo of him standing guard at one of the castles. I said they let you stand guard? He had a busby on. He was known for moving around to a lot of different bands. He said he had played with Red Hackle. He got to be Pipe Sergeant with the band and then suddenly announced that he was leaving the area. He was trying to bring his wife and kid over to stay with him. After, he had gotten his piping going with a website and everything. Then, one day he was playing, had a heart attack and died right on the spot.

John Rudolph came over. He had played in the Rutherglen band in Scotland. He married a girl here and had a couple of kids. She took sick, died and left him high and dry, so, he moved back to Scotland. He has since passed away. Another player from Rutherglen was interested in coming to play, George. When the band went to the World’s in ’77, Chuck went to his house to hear him play, and he passed the audition. Arrangements were made for him to come over, but our draft board came after him when he got over here. He hightailed it for Canada. He played with Clan MacFarlane. Later he played with Niagara, and he was the official bus driver. Every once in a while, he would call me and we would have a talk.

DD: One thing I have always been impressed with was we never had a lot of arguments when it came to band business. I realized it was because we almost never had meetings, just those little 10-minute meetings at the end of band practice when everyone was chomping at the bit to go home. We would have one annual meeting. We never had a lot of the in-fighting that I’ve seen in other bands. I think that is part of why the band has lasted so long.

RR: More meetings would have been a bad thing. Before you know it, everyone is saying Well, I’ve got something to complain about too! When am I gonna get my new kilt? [Roger laughs].

A lot of interesting people- mostly blue-collar guys.

The Worcester Kilties and Manchester bands got along well despite everything. It was a good relationship. We lent them equipment at times and vice versa.

DD: How many times have you been to the World’s to play?

RR: Let’s see. I went in ’64 with Worcester, and I went in ’77 with Manchester in Aberdeen. They used to move the World’s around, but now everything is in Glasgow Green. Manchester also went in ’95, but I didn’t go [neither did Dixon]. The drum corps was first in Grade 2 at that World’s. The next contest was Hunter Mountain, and the band sounded really good, and we started making money again.

DD: Any insight into how things have changed over the years?

RR: Oh yeah. The instrument itself. Synthetic bags, synthetic reeds and all kinds of products you can buy to make it easier and make the instrument more dependable.

DD: Are you fine with those changes?

RR: I am. Just amazing that these dealers have everything. All you need to do is give them your credit card number and a week later its in the mailbox. You can even buy bagpipe items on Amazon – some good, some bad.

Dixon : I am amazed at the cost of pipe chanter reeds- $17 or $18 each. I remember when I was taking piobaireachd lessons with Donald Lindsay in 1980, he suggested I write to D.R. McLennan for reeds. I got a box of 36 reeds for around $20. I still have the box and some reeds!

RR: The quality of the reeds has definitely gotten better. Now if pipe-majors aren’t satisfied with reeds, they send them back. Back then, you were stuck with them. Manchester tried a lot of chanters. Our first matched set were Hardies. They were very good, all wood. In ’77, when we went to Scotland, we struck up a conversation with the Irishman who was making plastic chanters, James Warnock. He wasn’t a piper, but he knew how to make things. We were talking about using tape on the chanters. He was trying to make a chanter which didn’t need tape. Of course, we know that still has not happened.

James Kerr was the first one that I saw using tape to tune a chanter. It was being done other places, but I wasn’t aware of it. He would come around and touch up the drones and make playing more enjoyable cause you had a good sound. Most of the tape is on the upper hand.

Back to chanters. I struck up a conversation with Andrew Warnock, a hell of a nice guy. We were staying at a place where he had come up with some of his wares. He said, Well, let me give you two of my chanters you can try out. He said, “I’ll be at Dunoon, and you can look me up there.” These were plastic chanters. He knew how to make them. The plastic was soft, it was not easy to machine compared to wood. It would bend. But I ended up bringing them both home with me along with some McAllister reeds he had given me to try. I told him I would buy all the reeds you have in that box. But he said, ” I can’t sell them to you, I need them for my business.” But he did give me a few, and they were good reeds. McAllister brothers were making good reeds then. We had gone to Dunoon, and I looked all over for him. He had a caravan he used to drive around. And they lived in Cookstown.

Anyway, I could not find him, so I ended up bringing the chanters home. And I liked them. Next band practice, I said to Chuck [Murdoch], I got these couple of chanters. I’ll give one to you. See what you think. He loved it. We ordered a bunch, and they are still kicking around. They are the chanters the band plays for Christmas concerts. They were flatter and blended with other instruments better. We played those chanters for quite a while, and Chuck got a good sound out of them.

Also, there was a guy named MacLellan making chanters. I think he was a pipe-major of Edinburgh Police. He got into the chanter-making business. I think it was Willie Bald’s father who got us a deal on those. We got a set of his chanters, and we didn’t like them. They were wood. Then, there was a fellow up in Buffalo. His name was Kenny Murchison. He was a real Scotsman, had a big square chin. We ordered a bunch of chanters from him. We didn’t like them either. We had chanters galore that weren’t being used because we had a brand-new set of Hardies, which were good.

DD: Speaking of Ken Murchison, I met him at the Syracuse Games once. He had an aluminum chanter he had made. I also remember he had a set of pipes that were somehow being electrically played because he had some kind of medical condition. Those two things are all I remember about him.

RR: Then, Gordon Tuck started making his own chanters. We never bought any of those, but the Worcester band did. They were messing around with chanters just like we were, trying to get the edge.

We also had good luck with the Sheperd chanters. We also had good sound with War-Mac chanters. These were a collaboration between Warnock and McAllister.

DD: I remember when I first started playing with Manchester, in the beer tent, other bands would come up and say our sound was what they tried to emulate.

RR: No matter what chanter we used, we always seemed to have a good sound. I can’t remember what we got after the War-Macs, maybe the Shepherds. They always get sharper, not flatter. If a band comes out playing the old type chanters, like the wooden ones, the judges will say you are out of touch and don’t like the pitch.

There was a band at Schenectady one year. I think they were from Texas. That was the only place they played around here. They had that old, flatter sound. It sounded really nice, with some bite to it. I always thought the plastic chanters, especially the Sinclair chanters, didn’t project the volume the way the wooden ones did. The Sinclairs became popular because somebody figured out how to make the holes bigger. The band never had those.

The wooden chanters, there was really no such thing as a matched set; the wood was still living! [Roger laughs]. But the plastic chanters, when you got a matched set, they were all the same. Pushing a button would punch the holes all the same.

All the good chanter makers keep introducing new models, each costing a little more. I guess the big chanter right now is the G1.

DD: So, Roger, you’ve been playing for 78 years?

RR: Yup, 1946.

DD: Think you have another 70 in you?

RR: I sit down a lot when I play now cause I’m not going anywhere. If I stand to play for long, my back kills me.

DD: You’d be right at home in Cape Breton. All the pipers up there sit when they play. And they play fast.

RR: Yeah, how ’bout that!

Our thanks to Roger Ritchie and Don Dixon for their work on this interview and for thinking of pipes|drums as the ideal place for it.

Do have an interesting story to tell? Just send us your ideas. We love to hear from our readers!

Hey Don, what a great interview of a great man and one of many influences in my time at Manchester.

I’d like to make one correction and add a little more color regarding the story about that first year at Cambridge (since it is about me 🙂 ). My bag didn’t blow out; my bass drone did not strike in, and being in the front rank, I didn’t want to attempt to re-strike and get dinged for a late attack. So, as you noted, I faked the performance. I was directing the band with a lot of movement, looking around the circle, to hide the fact that I wasn’t actually playing. I was keeping the bag nearly inflated (and could hear a few faint drone reed squeals); somehow we got through it.

Before closing massed bands, Chuck and I were speaking with one of the piping judges (who was close friends with Chuck), and he noted that he placed us 4th. I thought “There is no way we won that contest”, so I didn’t bother spending a ton of time tuning drones going into massed bands. I was pleasantly shocked when we were announced the winners (the other 3 judges had us 1st). After the excitement waned, I then panicked realizing “Holy crap, we have to follow the Frasers off the field, and we are not in tune”.

I love recounting that story, and learned a valuable lesson: never assume that you are not in a position to march off the field, and always be prepared to do so.

Cheers

Brian

Great interview. Honored to have played with both Roger and Don, and to still be a part of this great pipe band!

(Nice to see my dad, Jimmy Rankine, mentioned in the bit about the Worcester band. Who knows where we’d have ended up if they hadn’t recruited him from Scotland in 1956?)

David Rankine