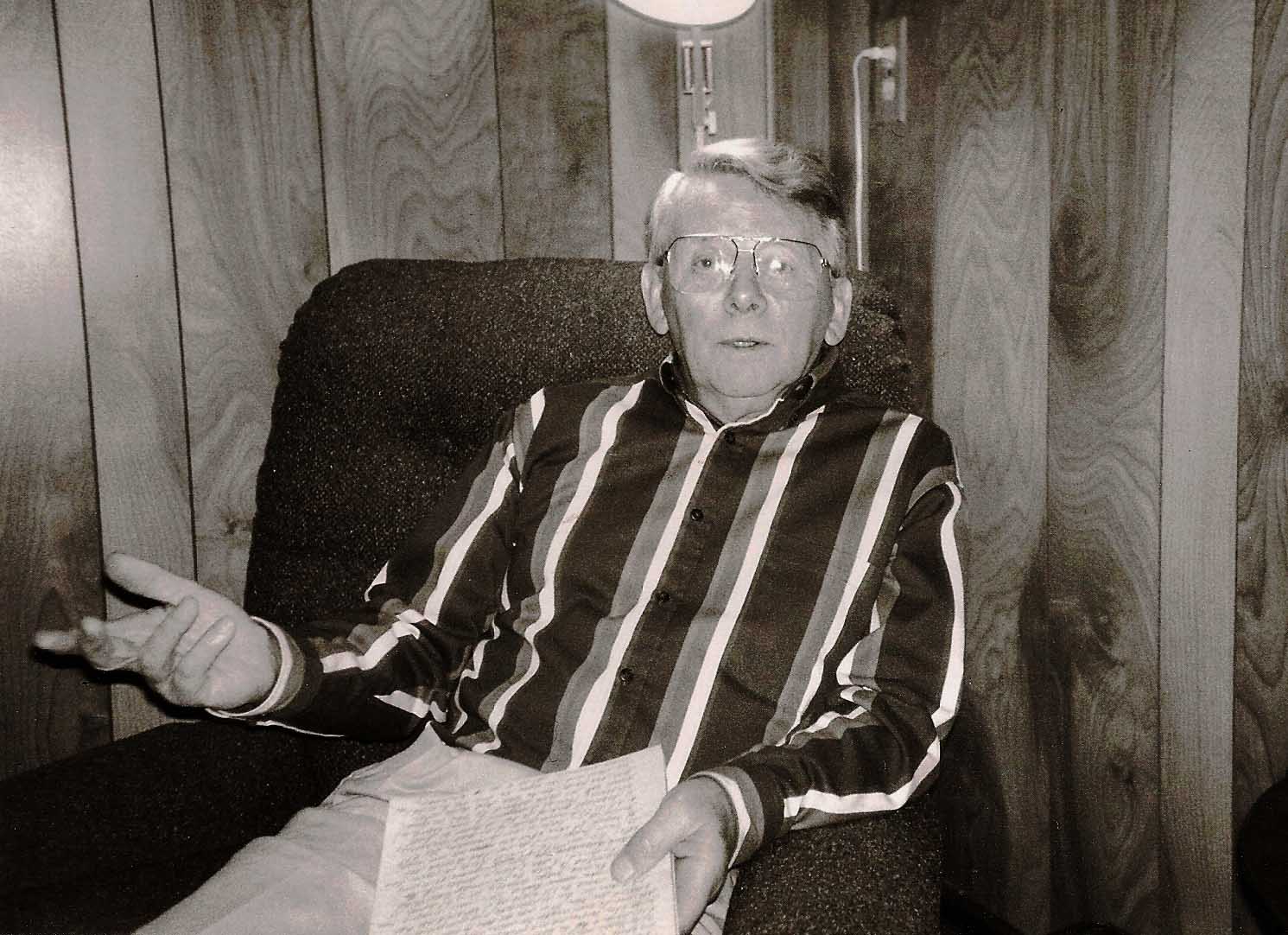

Jimmy McIntosh: the 1994 pipes|drums Interview from the Archives – Part 1

The piping and drumming world was saddened by the passing in South Carolina of James McIntosh on February 8th in his ninety-sixth year. Known as Jimmy to all who knew him, his inexhaustible commitment to passing along his knowledge of piobaireachd for the latter 50 years of his life is the stuff of legend, rivalling that of his own main teachers, Bob Nicol, Bob Brown and Donald MacLeod.

And the mark he made on piping in the United States is truly unsurpassed. To be sure, there was good piping in the US before he immigrated to America in 1982, with teachers like George Bell, Robert Gilchrist and Roddy MacDonald passing along their knowledge to accomplished pipers such as Jimmy Bell, Peter Kent, Ed Krintz, Albert McMullin, Burt Mitchell, Robert Mitchell, Jim Stack and others.

Michael Cusack of Houston at the time was a polished player under the tutelage of Scotland’s great John MacFadyen, and of course, Donald Lindsay of New York had spent his own time studying piobaireachd with the Bobs of Balmoral.

Less known is that McIntosh was an accomplished pipe bandsman before he discovered piobaireachd. He was the pipe-major of two Grade 2 bands, including the now long-defunct NCR Pipe Band, which he took to the brink of Grade 1, regularly beating top-grade bands at smaller contests.

It was piobaireachd, though, that consumed his life. He was a true evangelist of the ceol mor religion and seemed to be on a mission to convert United States piping to his righteous belief in the music.

We remember making the five-hour drive to Pittsburgh over a weekend in May 1994. He was well settled in the area after establishing the breakthrough piping degree program at Carnegie Mellon University, which continued after he retired under the late Alasdair Gillies and, currently, with Andrew Carlisle.

We were made most welcome by Jimmy and his wife Joyce, an accomplished piper herself. Never one to leave much to chance, he had prepared full written answers to framework questions we had provided in advance, one of very few pipes|drums Interview subjects to take such a cautious tack. Normally, prepared answers don’t work well, and he abandoned his notes after a few minutes.

As with all of them, the May 1994 McIntosh interview is a fascinating snapshot in piping history. At the time, he was in the middle of serving as president of the Eastern United States Pipe Band Association, where he had worked to create considerable – and not a little controversial – change. The EUSPBA was in a fractious relationship with the Pipers & Pipe Band Society of Ontario, at odds over issues of reciprocal standards of grading and judging, McIntosh’s association resolutely wanting to depend less on imported Canadian judges and more on American talent.

The newly formed Association of Piping Adjudicators, which would fizzle a few years later, had been lobbying big solo competitions in the UK to adhere to their policies and requirements. Many top-tier competing pipers had protested the situation in “The Boycott Year” of 1993 by sitting out the Argyllshire Gathering and Northern Meeting. There was a lot going on in the solo piping world, and McIntosh was a strong voice in much of it.

We will run the interview in four parts and include the original introduction to preface Part 1.

Jimmy McIntosh: the pipes|drums Interview from the Archives – Part 1

Jimmy McIntosh can be compared to the bagpipe itself: he is either liked immensely or greatly misunderstood.

The one thing that can’t be understood about McIntosh is his relentless· passion for the instrument. For one who was literally forced into playing the pipes by his father, he has made the bagpipe his vocation, his obsession, and his mission.

Piping for Jimmy McIntosh is not his pastime; it is his life.

James McIntosh was born in Broughty Ferry, a small village outside of Dundee, Scotland, in 1925. His father recognized the importance of music, and while his brothers were given the church organ and violin to learn, young Jimmy was marched off to learn the pipes at the age of eight.

His father in 1939 decided Jimmy would serve his country and enlisted him (unknown to his mother) as a band boy with the Cameron Highlanders – a move, as it turned out, that would introduce him to piping on a grand scale. In the ranks of his band were, among other greats, John MacLellan, Donald Macleod, and Mickey 16 Mac Kay. He was to stay in the army for ten years.

Upon his departure from the Camerons, Jimmy was absorbed into the pipe band scene in the Dundee area, as a piper with the MacKenzie Pipe Band. Shortly thereafter, he became pipe major of the City of Dundee, a successful Grade 2 band and, in 1957, he was asked to lead a new band sponsored by the emerging American technology company, NCR. Just as the NCR Pipe Band was at the brink of moving to Grade 1, Jimmy decided to pursue other piping interests.

In the mid-1960s, McIntosh rediscovered piobaireachd. He had the good fortune to be accepted as a pupil of Robert Brown of Balmoral, and for the next several years, enjoyed intense tuition from this piobaireachd master. It was during his weekly visits to Balmoral, under the wings of Brown and Bob Nicol, that McIntosh engrossed himself in ceol mor, and moulded himself into a master of piobaireachd himself.

In 1971 McIntosh won the Gold Medal at Inverness, and he went on to win most major prizes available, including the Portree Gold Medal in 1975 and Portree Clasp in 1976, and the Gold Medal at Oban in 1978. After taking ill at a Grant’s competition, McIntosh decided to retire from competition – a decision he would ultimately regret.

In the tradition of John MacDonald of Inverness, Donald MacLeod, and the Bobs of Balmoral, Jimmy McIntosh turned his devotion to teaching. Seumas MacNeill had introduced him to North America by bringing him as an instructor in the late 1970s to the Timmins schools in Northern Ontario, and soon McIntosh was taking part in and organizing his own “Balmoral” summer schools in the eastern United States. His popularity as a teacher spread throughout the country, to the point when, in 1982, he decided to immigrate to the United States.

McIntosh soon became president of the Eastern United States Pipe Band Association (EUSPBA). McIntosh quickly made his presence felt: he was criticized both positively and negatively for increasing the piobaireachd submission requirements for amateur and professional piping, making it more stringent than anywhere in the world; he developed examinations for judging; he presided over a transition from the old, established guard of the EUSPBA to an executive that promised to improve standards and raise the profile of the organization. Many in the piping world, if they know about the EUSPBA at all, are still waiting for that organization to emerge as something more significant.

Currently, he is Professor of Music at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. He teaches a four-year undergraduate course in Highland piping, the only such degree offered in the world.

In June of this year, he was awarded the Member of the British Empire medal for services to piping, and in October, he will travel to Buckingham Palace for the presentation ceremony. He lives in a comfortable home in a quiet suburb of Pittsburgh with his wife Joyce, also an accomplished piper. In May of this year, the editor of pipes|drums met Jimmy McIntosh for this revealing, candid interview.

pipes|drums: How is your health these days?

Jimmy McIntosh: Excellent. My doctor says that he hopes when he’s my age that he’s in the same shape that I’m in. I think age is a state of mind, and if you keep your mind active, then you’re young.

p|d: Weren’t you taken ill at one of the Grant’s competitions – 1976, I think it might have been?

JM: I don’t know what went wrong with that, whether it had been hunger or something like that, but it had been in the evening in the light music event, and I just felt light-headed when I was competing, and I stopped, but I’ve never been affected like that again. That prompted my decision to retire, and I regretted that decision afterwards.

p|d: In retrospect, you think you should have kept competing afterwards?

JM: Yes.

p|d: But didn’t you later return to competing a few times in the United States?

JM: I played three times in the United States in Friday evening piobaireachd competitions, and I played reasonably well. I had observed Open players in our association being very deficient in their preparation on the platform before the competition and also the quality of their instruments. My reason for competing on those occasions was to try to teach players from my performance those two aspects. I still think that that’s where we’re mostly deficient in our association, with the Open players. You can really start to win a competition before you even start playing your tune, and the bagpipe is 60 percent of the performance. I feel that they don’t hear enough good bagpipes here in competition. When I think back to Scotland and the indoor competitions at the Uist & Barra, the Edinburgh Police, Eagle Pipers, there would be 30 to 40 really good players playing, and you could sit there and listen to really wonderful bagpipes, and your ear was being trained to the good sound, something to aim for.

p|d: What’s the worst thing about piping today?

JM: In piping worldwide?

p|d: Sure.

JM: I think it varies worldwide. I would say that the different standards of bagpipe and professional bagpipe playing is a problem, and the lack of tuition is another. When I think of Scotland and the eastern United States, people seem to get to a certain level and think they no longer need tuition. At present in Scotland, very few of the competing players have teachers, and that’s a bad thing because you’re always learning. During a performance, the easiest person to deceive is yourself when you’re playing. You might think you’re playing well, and you go to play for someone else, and they pick you to pieces. If a person wants to be good, they have to study.

p|d: It’s reasonable to say that you have had one of the most well-rounded piping careers – piobaireachd, pipe bands, light music, reedmaking, teaching, politics. What’s still missing from the resume of Jimmy McIntosh?

JM: Something I still feel I would like to do is research. There’s a whole lot of research that still has to be done on bagpipe material for different reasons.

p|d: Are you talking about research in piobaireachd?

JM: Not so much on just piobaireachd, but on the instrument itself, on tone, and the historical aspects of piping. There is a lot to be done on that that I’m involved in at the moment.

p|d: Are you doing that through Carnegie Mellon University?

JM: Yes, in one of the piping courses I’m teaching, it’s very difficult to get reference books, in complete contrast to other musicians in the school who can go to the library and pick up books on just about any composer, or about Baroque music or just about anything you want to talk about, but there is nothing for bagpipes. For the last year, I’ve wanted to compile a reference book on 20th century piping, and make part of it about piobaireachds and the interpretation of piobaireachd, and to try to evolve a more accurate way of writing piobaireachd that could be played as it is written. We write piobaireachd today in a way in which we never really play it.

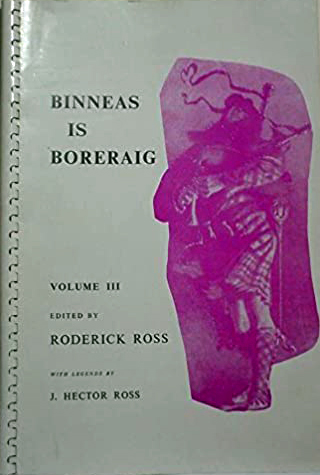

p|d: You’re a proponent of the work that Dr. Ross did with the Binneas is Boreraig works. Are you thinking of looking at piobaireachd in that sort of light?

JM: Yes, but going a lot further than that. There are many things that are used in other types of music that are beneficial to the reading of music, and we don’t use any of them in piping.

p|d: Such as?

JM: Such as cadences. We never talk about cadences in bagpipe music and in piobaireachd in particular. Cadences are just things on paper to us, whereas cadences are all relevant things in music, and they are important in piobaireachd if they are used properly because they can help in the interpretation of the music.

Such as the way we write our music. If you take the singling and doubling of a dithis variation in piobaireachd, we write the notes with the same values, but then we don’t play them as written, and we immediately tell the student not to play them as written. So why do we write them the same way? I’m trying to write the music as we play it. Why not double-dot the note in the singling and remove it in the doubling?

p|d: When can we expect to see some of the works you’re putting together?

JM: It’s difficult to say, but now that school has finished, I’m working on it again. I’m attempting to write about 30 piobaireachds out like that, and also to try to write out some of the tunes as Bob Brown played them, as well as how Bob Reid played some of the music. I’m writing to people to ask them permission to use stuff that has already been done.

p|d: How do you feel about teachers judging their pupils?

JM: That’s a touchy one. I know that Bob Brown didn’t like it. In fact, he was harder on his pupils than on others when he was judging because I remember him telling me that when that other person hasn’t had the benefit of his teaching, he wouldn’t expect as much from them. He would give them far more credit for having done something and maybe not having had a good level of teaching. I experienced that at Oban because I might have won the Gold Medal at Oban earlier if Bob Brown hadn’t been on the bench. That was the one time he was on the bench at Oban. Bob told me afterwards that in “Beloved Scotland” I didn’t have that first bar, and I recall Hector MacFadyen telling me the next day he had seen Bob Brown in a hotel the night before and he told Bob that he should have had the courage to give me first prize, even though he was my teacher. Finlay MacNeil won it that year with “John Garve.”

JM: That’s a touchy one. I know that Bob Brown didn’t like it. In fact, he was harder on his pupils than on others when he was judging because I remember him telling me that when that other person hasn’t had the benefit of his teaching, he wouldn’t expect as much from them. He would give them far more credit for having done something and maybe not having had a good level of teaching. I experienced that at Oban because I might have won the Gold Medal at Oban earlier if Bob Brown hadn’t been on the bench. That was the one time he was on the bench at Oban. Bob told me afterwards that in “Beloved Scotland” I didn’t have that first bar, and I recall Hector MacFadyen telling me the next day he had seen Bob Brown in a hotel the night before and he told Bob that he should have had the courage to give me first prize, even though he was my teacher. Finlay MacNeil won it that year with “John Garve.”

I’m not terribly keen on judging my pupils either because it can be a very awkward position. Even though you might feel that your integrity is good, from the competitors’ point of view, it is better that you don’t. If the competitor is somebody who has studied with you and they win, then it can detract from their prize, and that’s not right.

p|d: What about husbands judging their wives and vice versa?

JM: No, no, no. That’s a no-win situation, not only with wives and husbands, but with brothers or sisters or immediate family. There should be a hard and fast rule on that.

p|d: And what about businesspeople assessing their products in competition?

JM: It shouldn’t be done.

p|d: But this is coming from somebody who has been a reed maker for a long time and who helped develop the Naill chanter. You’re saying it shouldn’t happen, but I’m sure many people reading this are wondering why you did it yourself.

JM: When I was in business, I was representing Naill, but after I stopped with Naill, the ads that I had in the business when I was on my own never had any of that stuff in it.

p|d: What about chanter makers judging pipe bands?

JM: It’s terribly wrong to assume that every person who is involved like that is dishonest because I don’t think they are.

p|d: Nobody’s saying that.

JM: There are one or two people who are involved in business who are mercenary, and they look for any opportunity to promote their products. I think there are a lot of politics involved in the business.

p|d: We remember you saying in 1981 that successful competitive piping will go the way of successful competitive golf: to the United States. At the time, that statement seemed plausible, but now there has been a piping renaissance – and a golf one, too, for that matter – that has seen its resurgence in Scotland and continued development in Canada, while the U.S. still can’t maintain a Grade 1 band or another Gold Medallist since Mike Cusack’s success in the mid-’80s. What’s preventing the eastern United States from becoming the piping Mecca you once thought it would become?

JM: I wish I knew the answer to this. Perhaps the Gold Medals have lost their appeal; perhaps it’s not as important to pipers now to win it. I really don’t think that some of them have the determination that I had to win. They aren’t prepared to make a strong enough commitment. I see some good things in our competitions on the Friday evening. I think the fact that we give Open players a good environment to play in has altered their attitude, by making them become more professional in their approach. You have to be very single-minded about it and decide that that’s what you’re going to do and do it.

p|d: You started competing seriously after you turned 40. How much does maturity – as a person and as a player – have to do with good piobaireachd playing?

JM: I think that maturity can make piobaireachd playing much better and more musical because of your understanding of the music. I was playing piobaireachd when I was 15, but I didn’t understand it. In fact, I studied with Donald MacLeod, when he was my pipe-major when he was going twice a week to John MacDonald. Willie Ross had been my teacher in 1938, and again in 1943, and I had 16 piobaireachds from him in the period that I was with him. But I never really understood piobaireachd until I went to Bob Brown when I was in my forties.

JM: I think that maturity can make piobaireachd playing much better and more musical because of your understanding of the music. I was playing piobaireachd when I was 15, but I didn’t understand it. In fact, I studied with Donald MacLeod, when he was my pipe-major when he was going twice a week to John MacDonald. Willie Ross had been my teacher in 1938, and again in 1943, and I had 16 piobaireachds from him in the period that I was with him. But I never really understood piobaireachd until I went to Bob Brown when I was in my forties.

A person has to really feel the music; that’s the difference between what I call natural players and manufactured players.

p|d: Is someone born with the tools to be a great piobaireachd player, or can someone learn how to be a great piobaireachd player?

JM: You are probably born with a natural feeling for things in music. Some people don’t need to be taught things, whereas others you have to work and work with them. Some people don’t have to practise a whole lot and other people have to practise every night. That would bore me to death playing the same six tunes over every night, but I have had students who did that. If you talk to Donald MacPherson, he hardly ever practices.

p|d: Are there better piobaireachd players now than ever before?

JM: No, because of the lack of teaching and listening to piobaireachd. At the end of my competing career, there was a generation of new piobaireachd players missing and Nicol, although I got some of the same in Scotland. lain MacFadyen, John MacDougall, John Burgess, and myself though I’m older than those people) all retired in the 1980s, leaving a generation gap never got from anybody else until you get to the 30-year-old people.

Today, there are very few top competitors in their forties. I listened to the Glenfiddich competition last year, and the quality of the bagpipes was excellent, but there was a lot of what I would consider amateurish playing, a lack of musical understanding. Light and dark shading is missing. The playing is probably technically as good, if not better, but I think that musically it’s not as good.

Stay tuned for Jimmy McIntosh: the pipes|drums Interview from the Archives – Part 2 in the next while.

NO COMMENTS YET