Remembering Nigel Richard, 1948-2021, by Iain MacInnes

pipes|drums readers around the world are always encouraged to submit stories. Just drop us a line if you’re interested in contributing. The following piece on the late accomplished bagpipe maker and multi-talented musician, Nigel Richard, was provided by Iain MacInnes of Edinburgh, the renowned piper, Celtic folk musician and recently-retired longtime presenter and producer of BBC Radio Scotland’s weekly Pipeline program.

![Nigel Richard [photo Graham Barnes]](https://www.pipesdrums.com/storage/2021/01/Richard_Nigel_photo_Graham_Barnes.jpg)

He was also a great friend to many, displaying a musical eclecticism that effortlessly crossed boundaries and national borders, and which drew musicians from many different genres into his orbit.

His final years were spent in Pathhead, just outside Edinburgh, where his pipe-making workshop was housed in a large shed in the back garden, with overspill into his kitchen which was a mass of pots, pans, reeds, drones and piping paraphernalia. Out of this seeming chaos he produced top-class instruments, much sought-after by players of bellows pipes, and refined by years of experimentation.

When I first interviewed him for the radio in 1992 he was five years into his career as a pipemaker, and eagerly working on a keyed Border pipe chanter with a range from low E to high B, well suited to playing in minor keys. Having given an impressive rendition of “The Twa Corbies,” he explained his approach: “the chanter incorporates extended keywork that looks something like what you would see on a clarinet or an oboe, but it’s stuff that I’ve taken three years developing . . . it takes account of the idiosyncrasies of bagpipe fingering.”

In fact, this keyed chanter didn’t find a ready market in Scotland, perhaps because it was at odds with established playing styles, and he turned instead to making chromatic chanters on which the accidentals are produced entirely by cross-fingering. These proved to be much more successful, and the fruits are to be heard in excellent recordings from the likes of Ross Ainslie, Finlay MacDonald and Fraser Fifield. The final product didn’t come easily, and I know that Nigel spent long hours working on reeds, chanter bores and hole placements – the stuff that keeps pipe makers awake at night and leaves them bleary-eyed in the morning – before he was happy with the design.

His main focus was on Border pipes, the bellows-blown instruments that use a common stock for the drones, and have conically-bored chanters similar to Highland pipes. He favoured a robust sound (I know this from having borrowed his own pipes on more than one occasion), and he furnished his early instruments with a number of innovations. One involved an unusual drone reed design, each reed crafted from a solid rectangular brass block with the interior carefully tooled out, and with a cane tongue. He had a special trimmer for tapering the tongue, leaving the top end heavier than the portion near the binding. I’ve played a set of these reeds for close to 30 years and I can honestly say that I’ve scarcely had to touch them in all that time. They remain as stable and resonant as ever.

In many ways, Nigel was an improbable character to have made the transition to artisan pipe maker, in his case from a career in accountancy. He played the pipes, certainly, and was careful to demonstrate suitable cross-fingerings to his customers, but he wouldn’t have regarded himself as a piper. His passion rather lay in stringed instruments. He was an excellent cittern-player and guitarist, his musical tastes forged in the folk-blues scene of the ’60s, with a liberal dose of Moroccan and Cretan music on the side, and an enduring fascination with Indian ragas. He was also a fine accompanist of Scottish music, and the sight of Nigel bursting into the room with cittern in hand and a smile on his face was usually the harbinger of a good night’s music-making. In fact, he was very particular about the best chords for accompanying pipe tunes and was not afraid to make his opinions known (to other string players) on that count.

What drew him to pipe making, I’m not sure, but his timing was perfect. He did a course in musical instrument repair at Stevenson College in 1985, and two years later set himself up as a pipe maker. I think his earliest instruments might have been made at his home in the Trinity area of Edinburgh – I certainly have a memory of visiting him there, entering the house to the whir of the lathe and finding him clutching a new-made chanter, his shirt spattered in a cocktail of wood dust and neatsfoot oil (excessive attention to wardrobe was never a feature of Nigel’s lifestyle).

The early 1980s marked a turning point of interest in bellows-blown piping in Scotland. An old and much-cherished tradition, long moribund, was due for revival, and with the hard work of a number of individuals, coalescing under the banner of The Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society, the flame was slowly rekindled. The society organized concerts, lectures and even competitions, and from all this came the need for instruments.

In fact, I tend to see this period not so much as revival, but rather re-invention, bearing in mind that many of the instruments that emerged in the ’80s had significant differences from their 19th century precursors. For instance, when it came to smallpipes, long chanters in the key of A, to which Highland pipers could easily adapt, were favoured over the much shorter chanters pitched in E or F commonly found in museums (these are directly related to modern Northumbrian smallpipes).

Whatever the case, Nigel’s entry into pipe making coincided with a very marked upturn in demand for instruments. He set up shop at 152 Albert Street just off Leith Walk, trading as Garvie Bagpipes and working with the experienced woodturner Alan Waldron. His instruments garnered attention, and he was able to experiment and innovate, producing a number of interesting smallpipe designs and a mouth-blown alternative to his Border pipes which he called Garvie Session pipes. In time Iain MacLeod came on board to make his bellows.

Undoubtedly Nigel’s own presence on the wider folk music scene did much to publicize his work, and he was always generous with his time when it came to talking about bagpipes. He served as chairman of the Lowland and Border Pipers’ Society from 2003 to 2006, a period which also saw the blossoming of his personal musical interests.

He had appeared on a number of recordings over the years, but with the creation of India Alba in 2002, he found his ideal band. This brought together Nigel’s own strings with Ross Ainslie’s pipes and whistles, and two tremendous Indian musicians in Sharat Srivastava on violin and Gyan Singh on tablas – a fusion of Indian classical and Scottish traditional that was truly bold and imaginative. Nigel got to indulge his interest in ragas (“more than a scale, less than a fixed composition”, as he put it) with musicians who were utterly at home in the medium.

The band toured for over 10 years and made two excellent CDs, Reels and Ragas recorded in Delhi in 2007, and High Beyond, recorded in the Hartola region of the Himalayas in 2009. In this case, working at an altitude of over 8,000 feet proved good for the creative juices, but was rather less congenial for the bagpipes. “They sounded like they were being played underwater,” said Nigel, “it’s a simple physical thing of backpressure – all wind instruments are designed to have the back pressure of normal gravity.” The piping tracks were later re-recorded at sea level.

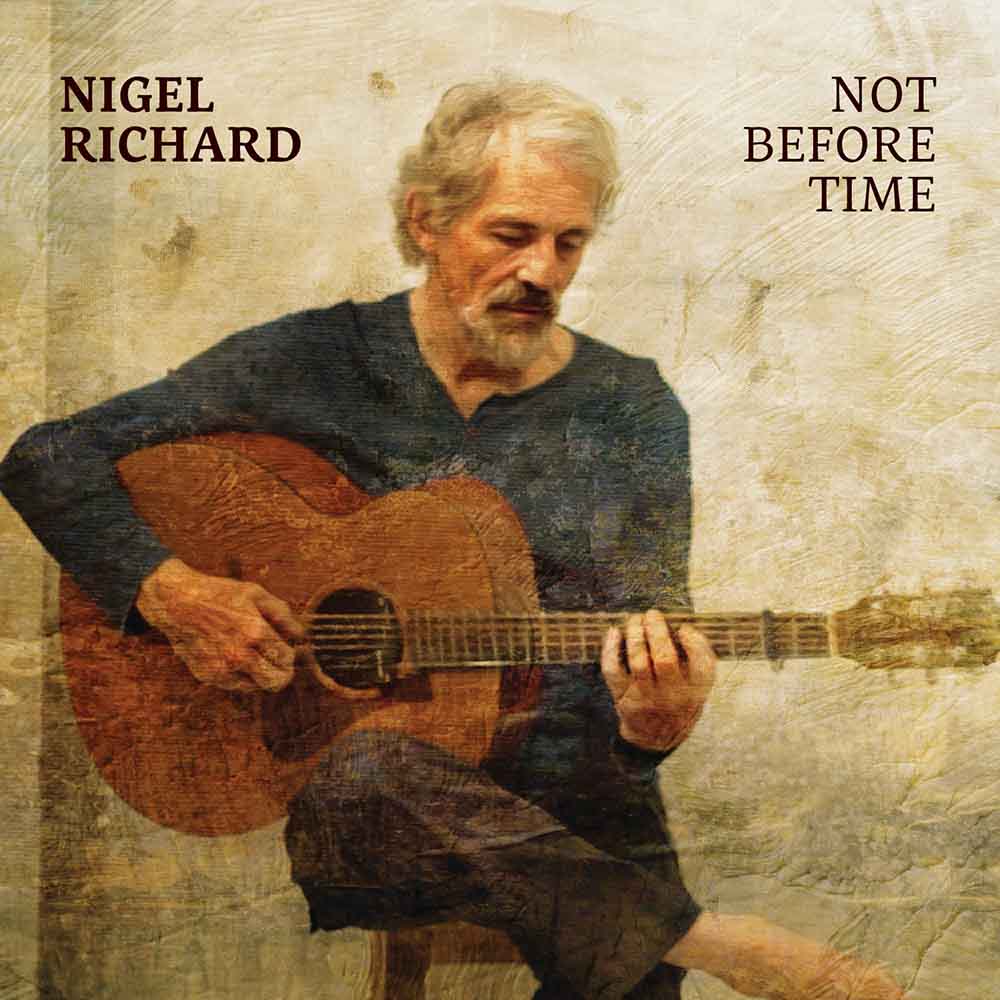

In 2019, aged 70, he fulfilled another ambition, producing an album of self-penned songs, but time was running out for him, and he died of cancer on the 1st of January this year. Kind, creative, witty, imaginative, we’ll all have our personal memories of Nigel, but he can certainly be remembered as one of the pioneers of modern bellows pipe design in Scotland.

Perhaps the last time that I spent several hours in his company was during the Scottish Referendum when a French film company visited his workshop to make a piece about Scottish cultural life. They captured some beautiful footage of him at the lathe, sun streaming through the window, the air thick with dust motes and wood trimmings. I suspect that he would have enjoyed the image.

If you own a set of Nigel’s pipes, treasure them, play them. If you own a set of his brass-bodied drone reeds . . . send them to me!

Iain MacInnes is one of the most accomplished pipers and Celtic musicians in the world. He has been a touring and recording member of the folk groups Smalltalk, the Tannahill Weavers and Ossian, as well as mounting several successful solo projects. He was for many years the presenter and then producer of BBC Radio Scotland’s Pipeline program. A frequent contributor to this magazine, Iain MacInnes retired last year and lives in Edinburgh and was the subject of a pipes|drums Interview in 2006.

Related

Iain MacInnes retires from BBC Scotland after 30 years

Iain MacInnes retires from BBC Scotland after 30 years

March 28, 2020

Iain MacInnes reviews “Play It Like You Sing It: The Shears Collection of Bagpipe Culture and Dance Music from Nova Scotia”

Iain MacInnes reviews “Play It Like You Sing It: The Shears Collection of Bagpipe Culture and Dance Music from Nova Scotia”

June 3, 2019

Iain MacInnes: the p|d Interview – Part 1

Iain MacInnes: the p|d Interview – Part 1

October 31, 2006

Iain MacInnes: the pipes|drums Interview – Part 2

Iain MacInnes: the pipes|drums Interview – Part 2

November 30, 2006

Thank you

Losing such an interesting eclectic person as Nigel Richard at what we now consider a young age is sad.

This comment is threefold

First. My only connection to Nigel is that I have a set of his border pipes. However, our pipes are organic and do become personal. Learning of their maker seems important

Second; Thank you Iain for letting the rest of us know more of just what an interesting eclectic person Nigel was.

Third: Thanks pipes|drums for carrying human stories and articles.

DJ.